“We wish to acknowledge that we are on Treaty 6 land…”

I always felt uneasy at those moments — “to acknowledge” means to “own the knowledge of,” and I had no clue what the Treaty said, no idea what made up Treaty 6 territory. I had never seen a map of the territory. I had no knowledge to own.

I learned that treaty land extends all the way from Jasper House in the west to Cumberland House on the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border —190,000 square kilometres. How can one imagine that much space?

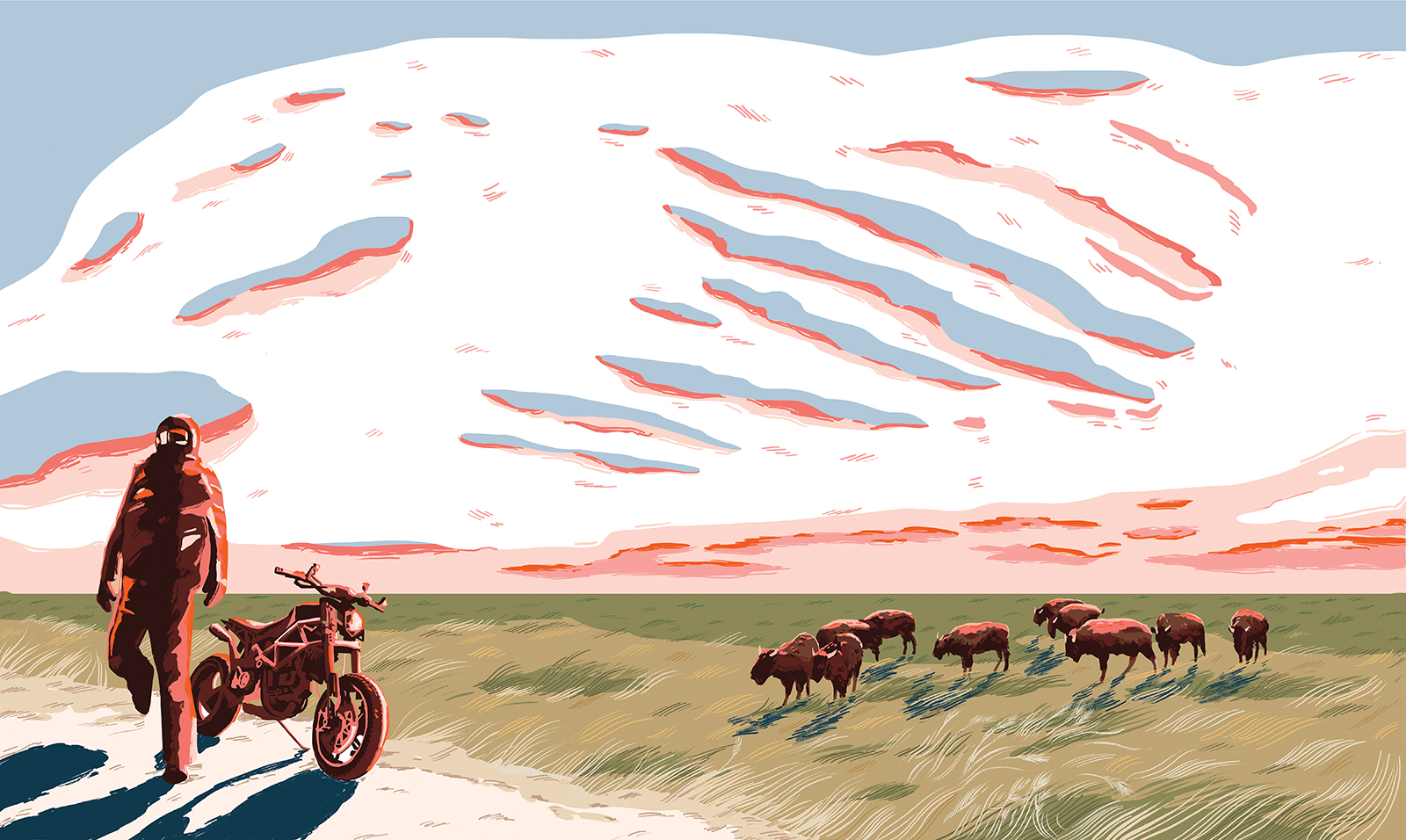

So I decided to ride my motorcycle around the perimeter of Treaty 6. I convinced my wife that I needed a new motorcycle for the trip, and negotiated a week off, the first week of Grade 2 for our son. (She thought the project a shameless boondoggle, I claimed it was research. As Tracey Lindbergh said in a talk last year, we all make treaty.)

Motorcycling puts the body back into travel. You take the road bumps in your bones, and the wind slaps you side to side like a punching bag. On the wide prairie, you feel like you’re riding on the skin of the world.

I rode for hours without seeing anyone. So much space. In that week I travelled 2,579 kilometres, yet only circled the prairie portion. If you combined Belgium, Austria and Switzerland you’d still have to add in half of Ireland to come up with equivalent territory. I had looked at the original Treaty 6 in Ottawa. It’s impressive — bigger than the Magna Carta or the British North America Act — yet, despite the size of the document, all that land was given away in one paragraph, one 246-word sentence.

As I neared the national historic site in Batoche, Saskatchewan, trees replaced the open prairie and grassland flowed down to the river and I reflected on how little I knew of my history. I’d heard something about the Riel Rebellion, led by a wild guy whom they hung, but as I pulled into the parking lot a metal cut-out of Riel greeted me with the quotation, “We did not rebel, we defended and maintained rights which we enjoyed and had neither forfeited nor sold.” This sounded reasonable and articulate, not crazy. These words came less than a decade after Treaty 6 was signed.

Here they called the events “The Resistance,” not a “rebellion,” and trees still define the strips of land giving each lot riverfront, lots that were to be obliterated by big rectangular sections. That’s what Métis leaders Riel and Gabriel Dumont were resisting, and what Major-General Frederick Dobson Middleton was sent to enforce.

(As a kid I’d treasured my Davy Crockett buckskin jacket and staged the siege of the Alamo in the backyard. I didn’t know Gabriel Dumont’s jacket was way cooler, and the Battle of Batoche more exciting.)

A young guide took a group of us through the church and rectory, and pointed out through an upstairs window. “The Gatling gun was set up on that hill over there by the cemetery. The priest got one bullet in his leg but they later patched him up. The Gatling gun was actually a terrible weapon.” She laughed. “It jammed all the time, sprayed bullets all over the place except where you were aiming, but it was an instrument of terror. Smoke coming out, the rattle of the bullets!”

She showed us the cenotaph in the cemetery. “Joseph Ouelette was 93! When the Métis knew they finally had to retreat — out of ammunition and using rocks and nails in their guns — Ouelette refused to go. He stayed to cover for his comrades as they escaped, saying he wanted to ‘get one more Redcoat.’ He was found shot in his gun pit.”

(I knew all about Jim Bowie, lying on his sick bed in the Alamo, taking a couple of Santa Anna’s men with him. Why didn’t I know about Ouelette?)

The guide gestured toward the river. “Middleton fitted out the Northcote, a cargo paddle wheeler, with a cannon and Gatling gun to attack the lower village. But Dumont, who owned one of the ferries, had his men string a ferry cable across the river at the height of the smokestacks. The Northcote steamed into the cable, lost its stacks and drifted helplessly down the South Saskatchewan as the battle raged.”

(The Northcote had made its first trip to Edmonton with 50 tons of freight in 1882, the year both James Joyce and Virginia Woolf were born. Why did I know about Woolf and not the Northcote?)

The guide said, “There used to be school trips here all the time, from Saskatoon, even Winnipeg, eight hours by bus. But there have been cutbacks and there aren’t so many any more.” As Billy-Ray Belcourt writes in his “Ode to Northern Alberta”,

history lays itself bare

at the side of the road

but no one is looking

Hayden King, who drafted the Territorial Acknowledgement for Toronto’s Ryerson University, now regrets it. “If it’s just a superficial box that you check… it effectively excuses [non-Indigenous settlers] from doing the hard work of learning.” Still, he says, if someone is hearing the acknowledgement for the first time, it has value.

Local Métis writer Chelsea Vowel says, “Territorial Acknowledgements drive me up the wall. They’re no longer unsettling” (pun noted). Yet when she attended a conference in Oakland, California, and there were no acknowledgements she found it “weird.” She wanted to know whose land they were on.

So Territorial Acknowledgments are initially useful, but can become as automatic and weightless as “Have a nice day.”

In the meantime, my journey continues with trying to learn some Cree. English is a noun-based language, but at the first class our teacher Lori Tootoosis said, “Oh yes, we have nouns, but we are not so interested in them.” Cree is verb-based. “I want to stretch your minds,” she said, and then told us that in Cree the colours are verbs.

The experience has already sent me back to Treaty 6, unique among the treaties in promising a “medicine chest.” My ancestors interpreted this as the equivalent of a first-aid kit. A thing. A noun. The Indigenous peoples interpreted this as the equivalent of Medicare. An ongoing process. A verb. How can you reach mutual understanding when the basic conceptions of language are so different?

Treaty 6 is many things — a linguistic construct, a social space, a landscape. I’m still coming to terms with the land. I want to ride the mountain portion this spring (though there are some dirt roads north of Edson and I might need another motorcycle). We need artists and activists, but, I would respectfully suggest, we also need road trips. For how can we acknowledge what we cannot imagine? It starts with the land.

The deal was negotiated between August 23-28, 1876, at Fort Pitt. Nine years later, as part of the Riel Rebellion, Métis warriors seized the Fort from the North-West Mounted Police.

From the Treaty text: The Plain and Wood Cree Tribes of Indians, and all the other Indians inhabiting the district hereinafter described and defined, do hereby cede, release, surrender and yield up to the Government of the Dominion of Canada, for Her Majesty the Queen and Her successors forever, all their rights, titles and privileges, whatsoever, to the lands included within the following limits…”

That’s right. “Forever.”

In exchange, the Crown promised that “no intoxicating liquor shall be introduced or sold” within the boundaries of reserves in the North-west Territories. Remember, this was before Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces.

“And the undersigned Chiefs on their own behalf and on behalf of all other Indians inhabiting the tract within ceded, do hereby solemnly promise and engage to strictly observe this treaty, and also to conduct and behave themselves as good and loyal subjects of Her Majesty the Queen.

“They promise and engage that they will in all respects obey and abide by the law, and they will maintain peace and good order between each other, and also between themselves and other tribes of Indians, and between themselves and others of Her Majesty’s subjects, whether Indians or whites, now inhabiting or hereafter to inhabit any part of the said ceded tracts, and that they will not molest the person or property of any inhabitant of such ceded tracts, or the property of Her Majesty the Queen, or interfere with or trouble any person passing or travelling through the said tracts, or any part thereof, and that they will aid and assist the officers of Her Majesty in bringing to justice and punishment any Indian offending against the stipulations of this treaty, or infringing the laws in force in the country so ceded.”

This article appears in the May 2019 issue of Avenue Edmonton