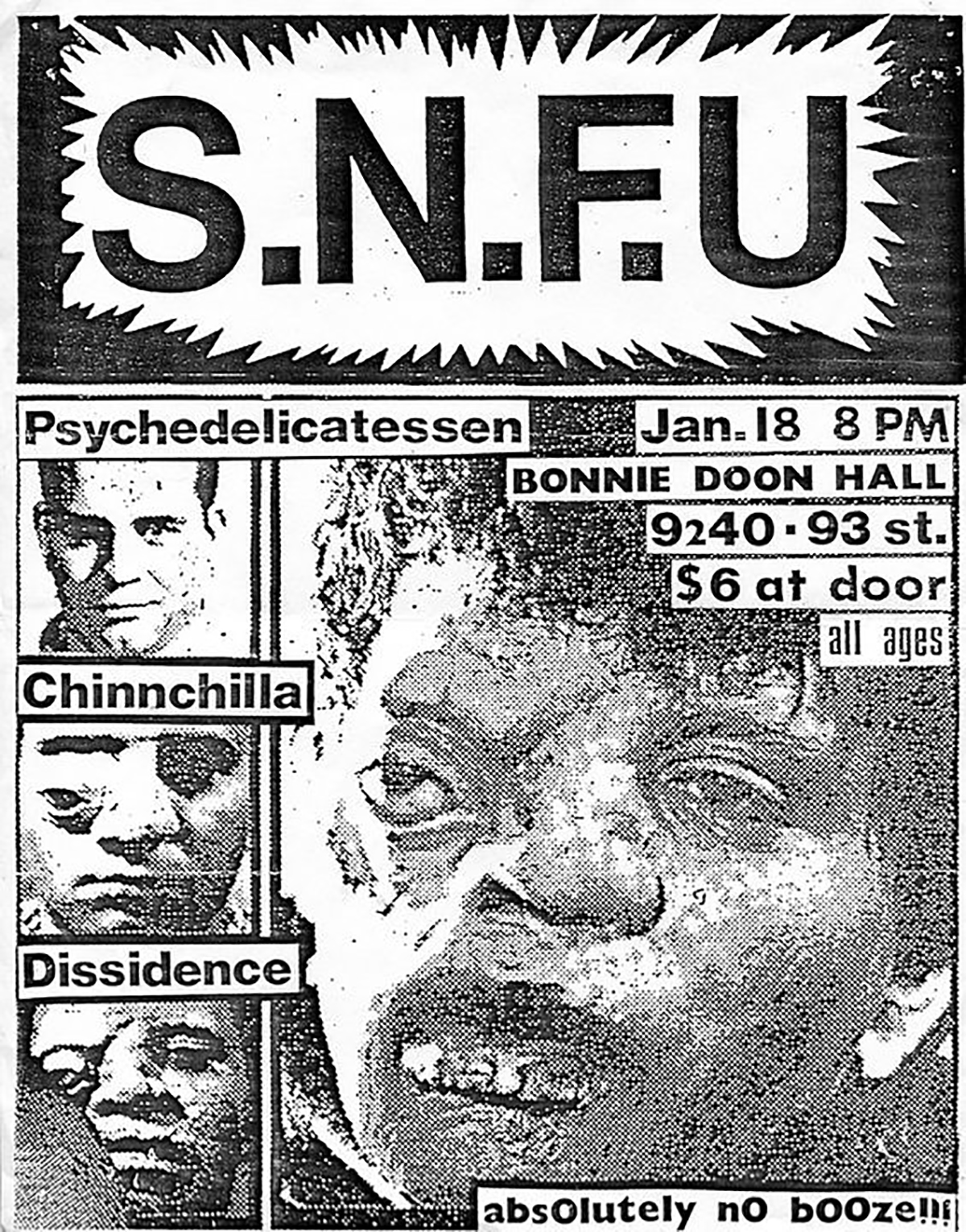

Nearly 20 years ago, I collaborated with the members of legendary Edmonton-born punk band SNFU on the concept for a book. “Concept” is important because the idea, like a lot of things in art, went to the “unfinished” pile.

With the passing of SNFU singer Ken “Chi Pig” Chinn in July, I opened these pages — after a couple of attempts to translate the text from a long-lost version of word-processing software. It had been years since I’d looked at the material. And it brought back a lot of memories.

After some polish, some vignettes — remembering the band’s early years in Edmonton — from that project will appear in Edify, as a tribute to one of this city’s true originals. There will be no more encores. No more leaps from the stage. But that doesn’t mean this city doesn’t share so many SNFU memories.

There are two schools of thought when it comes to punk music. The first camp is dogmatic; they believe punk music rose up rather abruptly and was reactionary. There is no grey area, a band is either “punk” or isn’t.

The second school, to which I belong, is that punk was actually a natural progression of rock music. To us, bands like the Talking Heads and the Clash, pigeonholed as “punk” acts in the 1970s, are prime examples. They borrowed heavily from other forms of music; the Clash, notably, saw punk as being closely related to the rockabilly ditties of the 1950s and the Jamaican reggae soundwave of the 1970s.

So, were the members of SNFU, Chi included, dogmatic punks? Not at all. They were definitely in the second category. Marc Belke was a metal child — Brent Belke, his twin brother, was a Kiss fan; drummer Evan C. Jones was an art-rocker who dug Pink Floyd just as much as the new hardcore stuff he was getting into. Meanwhile, Ken Chinn (the Chi Pig name would come later) had embraced the entire spectrum of New York hardcore — at the time, the most cutting-edge stuff on the punk circuit. So, while the core members of SNFU’s early lineup were embracing the punk-rock explosion that was late to hit Edmonton — they certainly weren’t evangelical about it.

The band officially formed in 1981 — singer Chi Pig met the Belkes through skateboarding competitions; they had become fast friends. Along with bassist Phil Larson and drummer Ed Dobek (who drummed for the Malibu Kens, a band that morphed into the locally famous Jr. Gone Wild), they formed Live Sex Shows, a punk-cover band.

“Brent really wanted to be in the band,” recalled Chi. “So we let him sing about half the set. We knew about eight songs, so Brent would sing four and then I’d sing the rest.”

Live Sex Shows played a few parties and even a hall gig before the band called it quits. But Chi and the Belkes decided to keep the nucleus of Live Sex Shows together; they enlisted Jones and a bassist only known to the world as “W.” (his real name was Warren Bidlock, but this is a punk-rock story, and punk-rock storytellers love guys with initials, not proper names) and created SNFU. The SNFU idea came up while the lads were having pizza — it was an era before band names made up of initials became commonplace; Marc suggested that using the military term “SNAFU” would be cool. His bandmates agreed, but decided to drop the “A” as they felt that if they ever developed a logo, the anarchy-lovin’ hardcore types (or at least, the types who liked the concept of anarchy in theory) would only circle the letter.

Jones — who carried the nickname “Tadpole” — had been playing in Edmonton bands since the age of 11. While playing in the Uncolas (“Not just another pop band,” Jones said), he recalled that a young Kenny Chinn who would knock on the window of the basement that served as the band’s rehearsal space. After being admitted, Chinn would listen to the band jam and stick his face into any comic he could find.

“I started playing the drums at the age of nine,” Jones said. “And it more or less saved my life. I always wanted to play music. I was playing pots and pans with wooden spoons ever since I could sit up. I mean, every kid is into something. Some kids like to collect bottlecaps, some kids go fishing, some kids join Boy Scouts. For me, my release was beating the shit out of a drum kit.”

In the early days of the band, Jones (who could also play guitar) used to help the Belkes tune their guitars.

The quintet began jamming (“jamming” being a rather loose description of what they were doing; the guys were still trying to learn chords) and writing songs in the basement of the Belke house.

To soundproof the room as best they could, the guys propped an old mattress up against the basement door.

“It was really noisy,” said Chi. “We were just learning how to play. There was a lot of swearing and stuff going on. It was a lot of fun.”

Jones recalled the Belke-basement days fondly, jamming with his new friends and learning to play hardcore standards like “Beverly Hills” by the Circle Jerks — except the band changed the title to “Bellamy Hill,” after the Edmonton landmark.

Beverly Hills,

Century City

Everything’s so nice and pretty

All the people look the same

Don’t they know they’re so damn lame

“It was a place where we would make some noise, get drunk and get stoned,” said Chi.

The Belkes were a traditional, Christian family. So, it wasn’t surprising that Mrs. Belke was appalled after stumbling on some of Chi’s lyric sheets while cleaning out the basement, including lyrics to a song called “Animal Lover,” which even Marc recalls was out of bounds and was never going to see the light of day as a song.

After six months of jamming, SNFU were evicted from the basement.

The ban forced the band to move into the Jones garage, in a house where Evan lived with his single mom, Eleanor, who was affectionately known as “Ma Jones” by the entire SNFU crew. The garage sessions that followed marked the first real creative spurt for the band. Most of the songs that appeared on the band’s first album were written in that garage, including the standards “Cannibal Cafe” and “Misfortune.”

Chi’s lyrical opening from “Misfortune:”

There’s fire at the end of the block

The people gather round to watch

Well instead of helping they just sit

As helpless people burn to a crisp

But there was only one problem; the garage got too cold in the winter to host the band, so a new rehearsal spot was needed when the mercury dropped.

By then, the band was starting to make some waves on the local live scene. “Society’s NFU” played their first official gig — a house shindig postered as “Val’s Pool Party,” no less — on June 5, 1982. More house gigs and small hall gigs followed. Russell Mulvey, a veteran of those Edmonton punk-rock days, remembered the first gig for SNFU at Spartan Men’s Club, a small venue that was a magnet for the small hardcore community in the city.

“The show sucked and my tires got slashed,” said Mulvey.

But Jones remembered that the band also had a house-party gig in Calgary around that time, but the set was scrubbed three songs in because one of the partygoers attempted suicide during the gig. Despite this disturbing omen, the band went on.

The band had got a new winter rehearsal space at a house (simply known as the “106 Street House” to people in the punk scene) in the Grandin district, a few blocks away from the Provincial Legislature. As the jamming got more and more serious — and the guys began talking about the band as a career move — ”W,” who wasn’t an accomplished bass player (after all this was punk rock, where proficiency wasn’t as important as passion), became more and more alienated from the group.

The breaking point came during one of those Grandin rehearsals. Right in the middle of a jam, “W.” hid behind a cabinet and refused to play.

“All you could see was his feet from behind the cabinet throughout the rehearsal,” laughed Jones.

Still, SNFU entered the studios at CJSR — the University of Alberta’s campus radio station — and, for the first time, rendered their stuff on tape. The band had been selected to record a song for a compilation record of Western Canadian bands. Because the band was still struggling in its search for a new bass player, Scott Alloy (real name, Scott Juskiw) — from local punk act Joey Did and the Necrophiliacs — filled in on the four-string. Alloy’s sub job went as good as could be. SNFU’s ensuing noisy chunk of punk rock “Life Of a Bag Lady/This is the End” was submitted for the compilation.

But, after the promoter had received tapes and money from the bands, he skipped town. It was all a scam. There was no record deal.

“I had heard that the promoter was spotted shortly afterwards driving a brand new car,” laughed Chi.

But it wouldn’t be long until the band got something on vinyl.