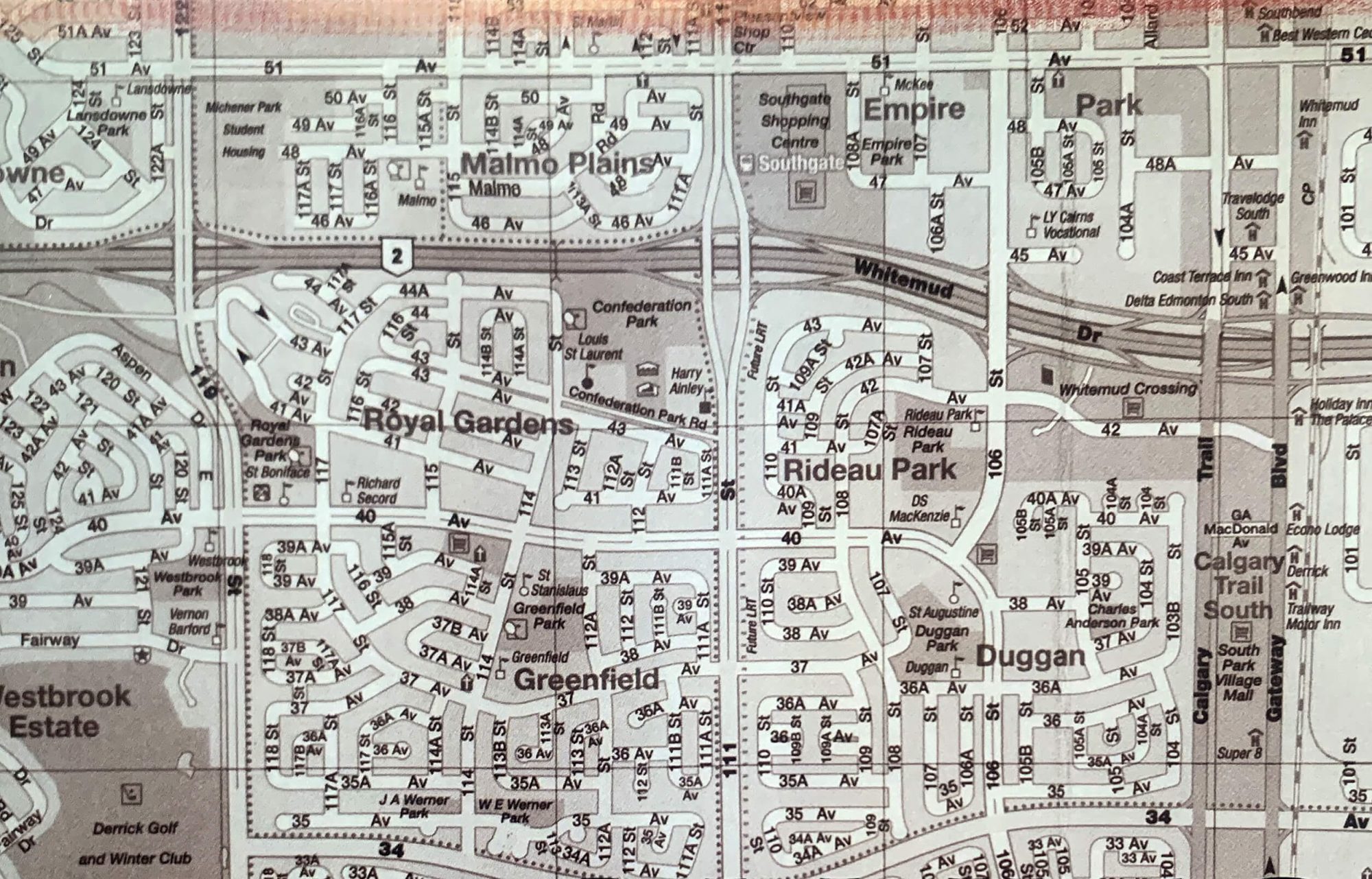

If there is a symbol of what our city is circa 2007, it might very well be the area around South Edmonton Common, where the froth and tumult created by billions of dollars worth of construction and commerce found. You’ve got IKEA, movie theatres, restaurants, dozens of big box stores, railroad tracks, the bowl of noodles otherwise known as Anthony Henday interchange. Not to mention the Edmonton Research Park just east of the Common, and a feeding frenzy of housing development west of Calgary Trail. It is, officially, insane.

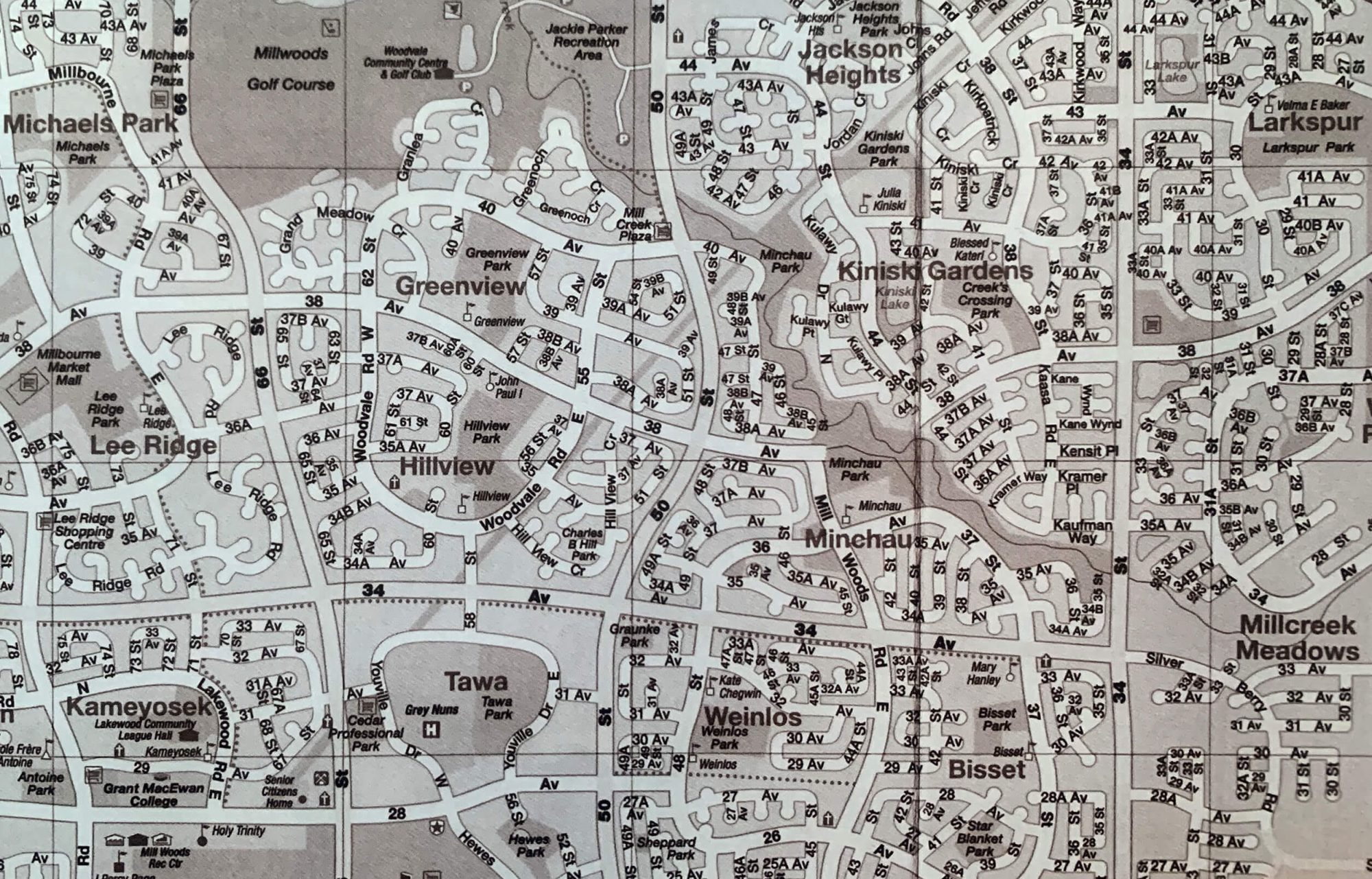

Yet this unrelaxed part of town shares one significant, if largely unknown, trait with more sedate regions of South Edmonton, such as the peacefully suburban Blue Quill, Twin Brooks and Mill Woods, and the clubhouse of the Derrick Golf Club. As different as these places are to the naked eye, the hundreds of businesses and tens of thousands of homes in the area — bordered by 122nd Street and 34th Street to the west and east, and by 51st Avenue and Ellerslie Road to the north and south — are all unified by one fact.

The land they’re on does not belong to them.

Or so say the Papaschase Band, something of a forgotten Cree tribe with roots in the Edmonton region. Whether they’ll get the chance to argue that is a matter that’s scheduled to go before the Supreme Court of Canada in 2008.

In 1877, the Papaschase were granted a reserve through an add-on to Treaty 6, a tract of land identified as Indian Reserve (IR) 136. But a decade later, after what the Papaschase say was the illegal surrender of their reserve, the Crown quickly commenced the sale of the land; by 1930 it had sold off every acre of the 40 square miles. (Using a conservative average of $100,000 per acre, recent news reports have valued the land at $2.5 billion. The unimproved land value, that is.)

Because of the sheer scale of potential damages, this land claim is nationally significant. It may also have implications for other First Nations who lost treaty members under circumstances similar to the Papaschase.

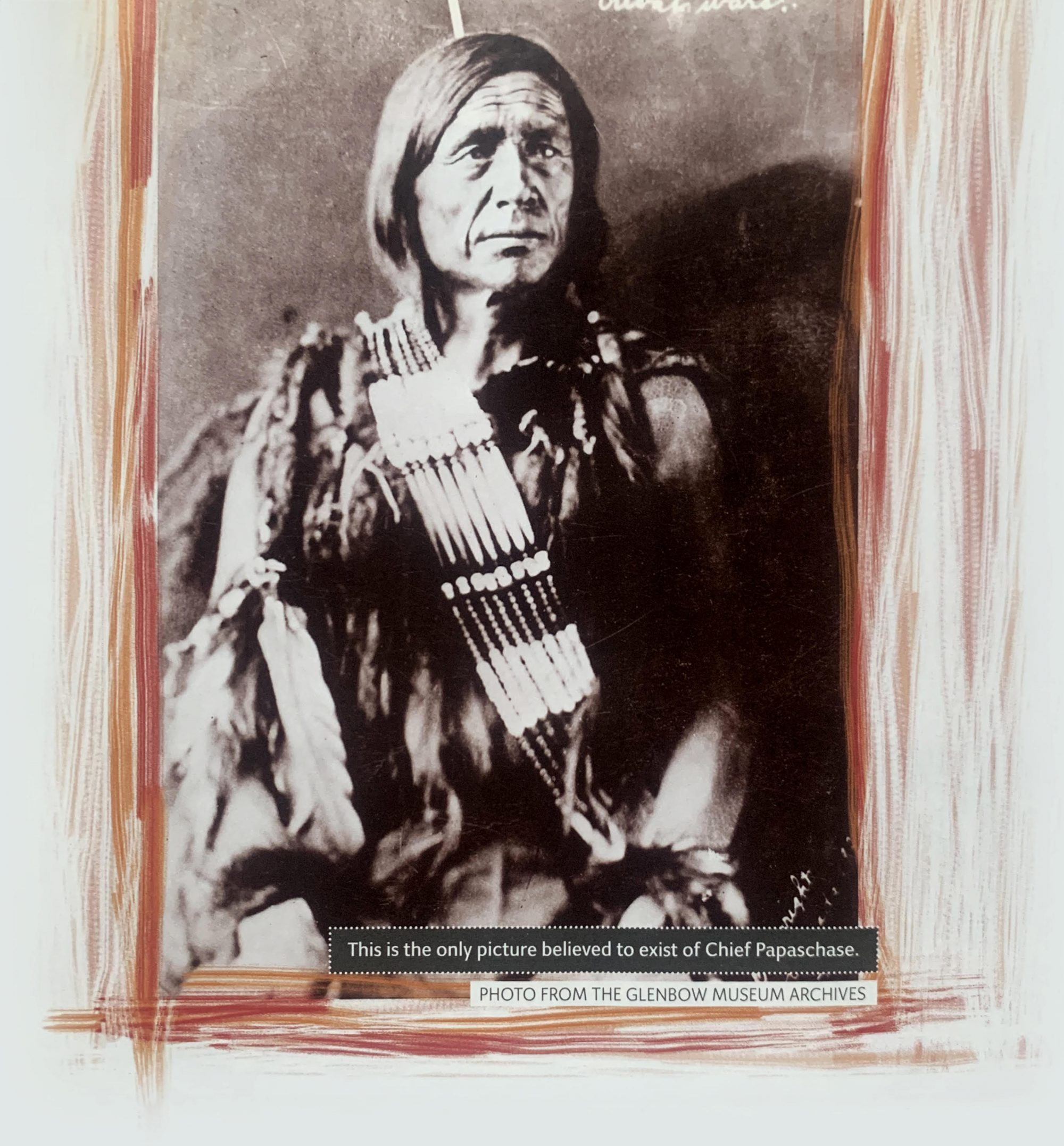

When the Papaschase lost their land, their band was also dissolved. Rose Lameman is the great-great-granddaughter of Chief Papaschase, and she has been Chief of the Papaschase Band since it re-formed under a chief and council governance model in 1999 (it’s now considered a legitimate band by other First Nations bands but is not recognized by the federal government). Lameman’s apparent good nature can’t hide the bluntness of her words in attempting to characterize the fate of the Papaschase. “Our land was stolen from us,” she says. “That’s basically what happened. I don’t think there’s any other way to say it.”

Dwayne Donald is a soft-spoken man, with a ready smile, but an intensity close beneath the smile. He’s an assistant professor in the faculty of education, so we meet at a coffee shop near the University of Alberta campus to talk about his heritage as a descendant of the Papaschase Band. We are surrounded by our city’s educated elite, and the irony is heavy, since we can safely assume that even here a random poll would reveal utter ignorance about the Papaschase.

“I think what happened to the Papaschase was about frontier logic,” says Donald. “And I think that logic still exists today.” In frontier logic, he explains, whatever needs to get exploited or removed to achieve ‘the goal’ is justified. “Perhaps it was Aboriginal Peoples then, and maybe it’s the environment now. But the logic is the same.”

As our city grew and modernized, says Donald, the stories Aboriginal Peoples tell of Edmonton were forgotten. That, he argues, led to a subtler but vital loss: we now fail to fully appreciate how related we are through he stories that spring from us living together here. He envisions a new kind of citizenship, one in which “the stories people tell reveal these relationships.”

That’s hopeful, but the reality is less encouraging. After 10 years of formally trying to be heard, the Papaschase have yet to secure he right to go to trial to argue that they were cheated out of their land. “Some days I want to quit,” says Lameman. “I’ve put family and relationships aside for this. And I wonder here we are supposed to go. What do we do? Squat on Crown land? I suppose we could, but who wants to do that? I’m not militant. I could be if I wanted to, but I’d rather negotiate.” She laughs softly, almost seemingly in spite of it all. “I won’t quit. You can’t say whoa in a horse race.”

If the Papaschase obtain the right to go to trial, a final decision is years away. Then perhaps we can concern ourselves with with what they want, and whether they will get it. But of more immediate interest for those living in this city is: Who are the Papaschase? How did they lose their land? And what does it mean about our home?

It began with Chief Papaschase, when he and his five brothers moved to the Edmonton region with their parents in the late 1850s from around Lesser Slave Lake. They lived a typical Cree life, ranging the area and setting up camps as they followed buffalo, berries and fish throughout the seasons.

On August 21, 1877, Chief Papaschase (who was also known as John Gladu Quinn) representing more than 200 members of the Papaschase band, signed the add-on to Treaty 6 giving them a reserve, although it took another three years to agree on the size and location.

The location seemed cursed almost from the start. Early in 1881, Edmontonians sent two petitions to Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald demanding that the Papaschase be relocated, the rationale being, in part, that they had no right to the land “not being natives of this part of the country.”

There was no small hostility during this period. Frank Oliver, founder of the Edmonton Bulletin and one of Edmonton’s most celebrated pioneers, proved particularly venomous in his remarks about the Papaschase. In an 1881 editorial, Oliver characterized the band as a questionable group of half-breeds led by a chief, “six or seven of his lazy brothers, one or two Indians and all the old squaws who generally hang around each of the Company’s forts.” He called for Ottawa to void the Papaschase reserve, and to hand the land over “to better men.”

But the band’s troubles had already begun. By late 1879, the buffalo had disappeared. Famine and starvation were general across the western reserves. The government had failed to fulfil some of the most basic agreements of Treaty 6, such as providing sufficient agricultural tools and seed. Even some basic annual payments were being witheld.

In 1885, the government’s Half Breed Scrip Commission arrived in the Edmonton region. Treaty Indians were eligible for scrip (a promissory note entitling them to a certain amount of non-reserve land or money) if they could show mixed-blood ancestry. The condition for accepting scrip was the loss of Treaty status. It was both a blessing and a curse: it perhaps saved many Indians from starvation, but the loss of Treaty status would return to haunt them.

Initially, 12 members of the Papaschase band accepted the scrip. The Chief and 60 band members applied for scrip in the summer of 1886. The remainder who could make a case that they had mixed blood soon followed. This fact is at the core of the argument made against the Papaschase by the Crown: this was the deal and they took it. At that point, they ceased to be Treaty Indians, and therefore ceased to have a claim for reserve land or Treaty Indian annuities. Whatever the reason, there’s nothing that can be done about it now.

Historian Dr. Clint Evans, who prepared a report for the Crown used in the first phase of the Papaschase’s legal action in 2004, offered the interpretation that it was primarily the surrender of Treaty status, effected by individuals taking scrip, which led to the band’s decline and eventual demise. There was no clear evidence, he concluded, that the band was in any way coerced or tricked into taking scrip so that the Crown could dissolve the band and return the land to the settlers. There was no plot.

Yet some Papaschase did not take scrip. Some stayed on the reserve; others moved to other reserves or Métis settlements. By late 1887, the government insisted that those remaining either leave or move to the Enoch reserve.

In 1888, with pressure mounting from the settlers and civic leaders of Edmonton and Strathcona, the Department of Indian Affairs arranged a “surrender” meeting of the Papaschase reserve. On Nov. 19, just three members of the band living on the Enoch reserve agreed to surrender the reserve. The government’s Indian Act stated that a majority of the voting members of the band had to be present at a surrender vote. Expert research on Treaty pay lists of the day presented in court argue that there were at least 10 and as many as 20 Papaschase in the area who were eligible to vote (band members who had not accepted scrip, who were male, and who were over the age of 21). These pay lists suggest there were no fewer than eight on the Enoch reserve, where the vote was held.

So, argue the Papaschase, no matter the criteria, a majority of eligible voters did not attend the surrender meeting. It didn’t matter. The vote was taken and the reserve declared surrendered. This was the end of Papaschase ownership of IR 136. Since Chief Papaschase had taken scrip, the loss of the reserve also effectively spelled the end of the Papaschase Band’s existence.

Chief Papaschase died in 1918. The band did not re-form until 1997. But Lameman says that non-profit organizations did form periodically since the 1930s to get their story out. It was largely the aboriginal historical method — storytelling of the kind Dwayne Donald says binds us together — that kept the Papaschase ember glowing.

“My dad’s childhood is a good example of how it was kept alive,” says Donald. “Relatives and friends would come over to his grandmother’s house, where he was raised, and often they talked about the surrender of the reserve. His grandmother was born in 1869, so that was a very direct link to that time.”

While the Treaty Papaschase (those who once had Treaty numbers and a band) kept the oral tradition alive, The Papaschase of Métis heritage kept close track of their genealogy relative to the original band. When they joined forces in the late 1990s, they embarked on getting heard legally. “We decided on the chief and council structure, elected a chief and a council, and then basically got to work to get where we are today,” says Lameman.

Which begs the question: Where, precisely are they today?

I meet with Ron Maurice, a Métis lawyer who is not a Papaschase member, in a prosperous middle-class Calgary suburb where signage features First Nations symbols. He took the case on a contingency basis, and has worked for free for eight years.

“This whole case has shaken my confidence in the justice system. I’m proud to be lawyer and to be part of the justice system,” he says. “But this case is very frustrating. I feel there are people who have gone out of their way to not have this case heard, to rationalize, and to arrive at a decision without hearing all the evidence.”

The Papaschase filed their lawsuit against the Crown in 2001, claiming that the government caused the dissolution of the Papaschase Band through various breaches of Treaty 6 and its fiduciary duty to the band. Since then, the lawsuit has been bogged down in a back-and-forth battle.

In 2004, the Crown made a motion to have the lawsuit summarily dismissed, a motion granted by Court of Queen’s Bench Justice Frans Slatter. The Papaschase appealed, and in December of 2006, Slatter’s decision was indeed reversed by Justice Jean Cote of the Alberta Court of Appeal, who granted them the right to go to trial. That decision was immediately challenged by the Crown to the Supreme Court, which has decided the matter is of interest.

Michele E. Annich, a lawyer for the attorney general of Canada in the proceeding before the Supreme Court, says the Crown’s basic position will be that “the Court of Queen’s Bench did not err and that there was ample evidence to support a summary dismissal of this action on the merits.” In other words, because the ancestors took scrip or moved to other reserves they lost their Treaty status, and that because such a long period had passed without legal action in the interim, going to trial is not warranted.

It’s not difficult to understand the Crown’s motivation. The government must challenge, or at least subject to strict tests, the authenticity of every claim, because it’s in the country’s fiscal interests to do so. If every First Nations claim was met according to actual loss of potential income, the government might be immediately bankrupt.

Yet the Crown’s argument — that the plaintiffs lack the right to bring the claim — appears to Maurice to be a circular, illogical argument.

“It’s almost as if the Crown is using sleight of hand,” he says. “Their argument is that, OK, when people took scrip and then the government moved, or pushed, everyone off IR 136, the government stopped keeping a pay list, which meant that effectively there were no more Papaschase. If there was no band pay list, there was no band. Which means, by that logic, there can’t be anyone to properly pursue this claim, because the Papaschase don’t exist.”

Should the Papaschase ever actually get to trial, what they want can be reduced to three elements. The first is land that can be called the Papaschase Reserve. Where that would be, and how much land would be granted, is a factor the band hasn’t even considered yet. That would be way too premature,” says Lameman. All that’s clear is that they are not suggesting something as ludicrous as getting their original reserve back. “We don’t want to do what was done to us,” says Lameman.

The second thing they want is financial compensation for the loss and use of that land. Again, details have not even been broached by the band. “We’re looking at it from the perspective of obtaining restitution for the loss of the land,” says Maurice. “We’re talking about either the replacement value of the land or replacement lands somewhere else.”

The third aspect of the claim is treaty reinstatement for those who lost it due to their ancestors taking scrip. But it’s possible none of this will matter a whit after the Supreme Court rules.

“If we lose that, then, really, we’re done,” Maurice says. “If the Supreme Court upholds the Crown’s appeal that we don’t have the right to go to trial, then it’s over.” Not just for the case, either. The fight to gain legal status as a band will effectively end, and the Papaschase will be reduced to one of history’s footnotes.

But if the Supreme Court denies the Crown’s appeal, then the Papaschase get to go to trial and be heard, “which is at the very least, what they’re entitled to,” says Maurice. A settlement and claim may result. The money could be astronomical, given the value of the land today and the loss of income from that land over the course of 120 years. But even for those who might benefit from it, it’s not finally what’s at stake. Dwayne Donald says it’s having the story heard that’s ultimately important, not just to the Papaschase, but to everyone who lives in the area. “If we don’t understand and acknowledge the way things happened in the past, it doesn’t bode well for our future, for trying to overcome frontier logic.”

Pasikôw: The Papaschase Cree and the Story of Edmonton

>> 1877: Chief Papaschase signs an adhesion to Treaty 6. He is promised 128 acres per capita, or approximately 50 square miles.

>> 1880: The government surveyor arrives. He calculates that the Papaschase are entitled to 48 square miles. An Indian agent cuts that to 40 square miles.

>>1885 and 1886: More than 70 members of the Papaschase accept Métis scrip (cash or non-reserve land for those of mixed blood) and forfeit their Treaty status.

>> 1887:The government takes a vote attended by three, still Treaty, members of the reserve. The land is surrendered.