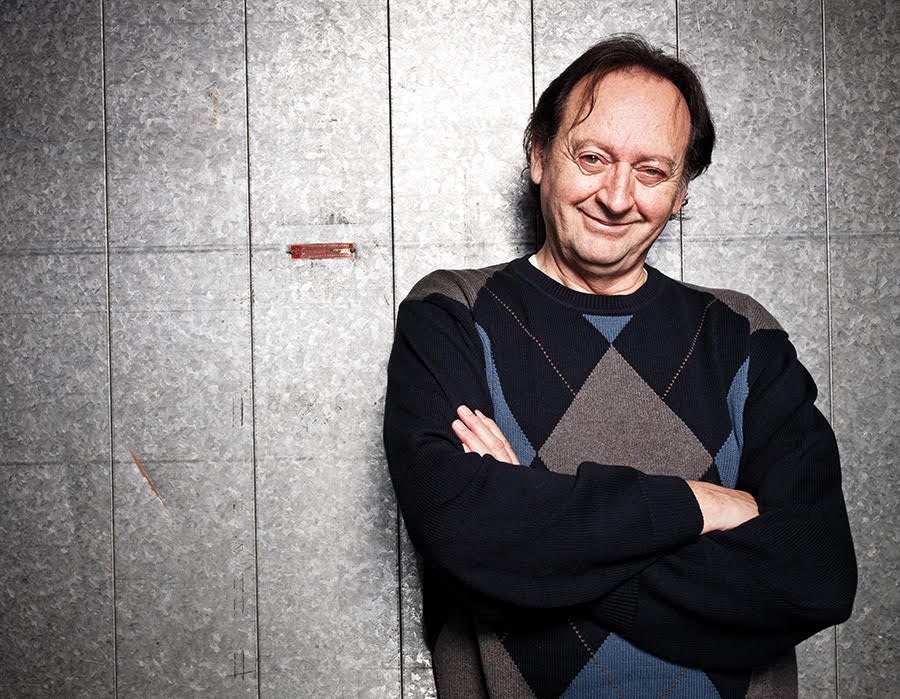

Joe Flaherty’s tall stature almost fills the Global Edmonton studios’ doorway as we leave the green room. We’re on the hunt for the old make-up room he remembers from his SCTV days. He pauses, eyebrow raised, eyes dancing, before releasing a Count Floyd howl that echoes down the hall.

The funny thing about Count Floyd, Flaherty explains, is that during his SCTV years, only one person ever asked why the character howled like a werewolf, even though he’s supposed to be a vampire.

I ask him, “So, why did you do it?”

“The howl just worked,” he says, shrugging.

Back in the ’70s and ’80s, Global was ITV, producer of SCTV, and Flaherty frequented the hallways with comedy legends like Dave Thomas, John Candy, Catherine O’Hara, Eugene Levy, Andrea Martin and Rick Moranis, all stars on the seminal sketch comedy show.

But, with many doors to choose from, Flaherty is stumped whether to go left or right. He says the studio looks pretty similar to those days, but now he can’t find the room where the cast sat for hours as hair and makeup added prosthetic noses or cheekbones that transformed Thomas into Bob Hope and O’Hara into Meryl Streep.

While the actors sat in the makeup room, they generated stories, bits and gags, and watched their co-stars on a TV monitor as hours of skits were recorded and later broadcasted on CBC and NBC. The crew would even run out of the room, makeup partially complete, to give the actors suggestions.

Often, according to Thomas, the makeup artists themselves were a source of inspiration. One even suggested he stick out his chin when talking like Bob Hope. It suddenly completed his impersonation because, not only did he look like Hope, but the adjustment to his mouth changed his voice to just the right pitch.

The idea for SCTV originated from the Second City Theatre, an experimental comedy group that was rooted in Chicago in 1959, then grew a branch in Toronto in 1973. After many of the Second City comics were recruited by Saturday Night Live, including Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi, the Toronto chapter’s producer, Andrew Alexander, and his partner Len Stuart wanted to create their own TV spin-off.

Born in 1976, SCTV was initially produced from the Global studios in Toronto. Two years after it hatched, Global couldn’t justify the high production costs of a show that required so many actors, costumes and sets. The show stopped airing for a year between 1978 and 1979, but Alexander, not wanting to let it die, decided to approach Charles Allard and Doug Holtby at Allarcom, the production company that owned ITV, to see if they’d be interested in producing the show from Edmonton.

“It was produced on a shoestring budget in Toronto and we thought if we put some resources into it, we would have something,” says Holtby, SCTV‘s executive producer during its Edmonton years.

It was bigger than they expected. So big that, after a year, the show (now called SCTV Network 90) was picked up by NBC, who increased its run time from 30 minutes to 90 minutes an episode. The episodes ran late-night Fridays – making it a sort of sister-show to SNL.

But the new format also made the cast’s already tight schedule very challenging.

According to Flaherty, the cast would sometimes work until two or three in the morning. “We were doing everything – writing and performing, sometimes even producing for the show. There was no time for anything else. We were like monks in a monastery.”

The fictional town of Melonville was created as the backdrop for the faux network. While Melonville entered the picture before SCTV came to Edmonton, the small fictional town provided the perfect setting for a struggling TV station because of its seclusion, which mirrored the reality of filming in Edmonton. While in Toronto, the cast also formed station characters, such as the obnoxious owner of SCTV, Guy Caballero, played by Flaherty, and station manager, Edith Prickley, played by Andrea Martin. During its time in Edmonton, these characters were more frequent and wove the sketches together through behind-the-scenes plots about the inner workings of a TV studio.

Being in Edmonton meant there were no fancy Hollywood parties, and no gaggles of fans leering at the cast in public. But the isolation also meant that SCTV kind of flew under the radar when it came to the expectations of the entertainment industry. NBC would send out executives on occasion to make suggestions, but the cast largely dictated the creative content, and often dodged requests from higher-ups.

When NBC executives worried that young children might still be up at the start of the show, and suggested sexual content be reserved for the latter half (but drug-related stuff was OK) the cast balked. Thomas recalls an executive saying, “‘Wait a minute, wait a minute, you don’t understand. We’re the network. We’re telling you to do this.’

“And I said to them: ‘No, you don’t understand. We’re in charge of the creative on the show. And if you don’t like that, you can fire us and stop the show. That’s what we’re willing to put on the line here.'”

“We were like spoiled kids,” says Flaherty. But it wasn’t just about the control; the crew wanted the skits to be the best possible. If the set for one skit was ready, but the actors came up with something they thought was better in the middle of the night, they’d call the producers to change the sets, Flaherty admits.

Luther Haave, former vice-president of operations for ITV, once got a phone call at four in the morning, requesting a Viking ship for the next day, for a sketch about Vikings further tormenting the English by bringing along bees on their raids. A few days later, ITV’s carpenter crew completed the ship, a huge prop on a 40-foot long hydraulic driver that allowed it to jolt back and forth like it was at sea. According to Flaherty, the skit was a nightmare to shoot because the cast had to do so many takes. John Candy ordered a vodka punchbowl, and by the endof filming, the hair stylist was passed out drunk at the bottom of the boat, says Flaherty. The boat cost thousands of dollars and the skit wasn’t particularly successful.

But there were other sketches that made up for the money spent, including all of the skits involving Bob and Doug McKenzie, the tuque-wearing hoser brothers who came up with ingenious plans, like how to bamboozle beer manufacturers by stuffing a baby mouse into a bottle of beer, letting it grow and saying it was there all along – just to get free beer.

While the cast normally rebuked any creative suggestions, in the case of Bob and Doug, played by Moranis and Thomas, the idea was born from a request from the CBC for more Canadian content. Though, really, Bob and Doug were created as a mockery of the Canadian content issue. “It just seemed stupid to us to mandate that, because it was actually a Canadian show, shot in Canada with a Canadian cast,” says Thomas. So, they decided to create the most stereotypical characters possible, who in turn became the two most popular characters on the show.

There were parades when Moranis and Thomas visited different parts of Canada and sometimes the United States. The duo put out an album that included a hit single with Rush’s Geddy Lee, “Take Off,” that made the Billboard charts in 1982. Strange Brew, the only SCTV-related movie, featured the brothers in 1983. In 2009, Global aired a cartoon about their exploits. “There aren’t a lot of cultural icons [in Canada] . You have the Mountie, the beaver, maybe John A. MacDonald, and then the list gets thin pretty fast,” says Thomas, a native of St. Catharines, Ont. “Bob and Doug were quickly embraced by Canada as non-threatening, beer drinking, Muppet-like icons.”

Most of the content was carefully written, but the Bob and Doug skits were improvised fillers with a set that consisted of discarded beer cans and Canadian maps, a budgetary dream. Thomas recalls: “The producer would come to us and say, ‘We don’t have the sets for the Sammy Maudlin thing ready yet. So, we’re going to shoot a bunch of Bob and Doug.”‘

Count Floyd also worked as a “minute-eater,” says Flaherty. The character came to him after Eugene Levy wrote a parody of the 1940s film Madame Curie. Count Floyd – the alter ego of “Floyd Robertson,” SCTV‘s fake newscaster – was a vampire who did intros and extros for fake horror films, including one about “evil pancakes.” (The most frightening part was John Candy swinging a plate of pancakes towards the screen in mockery of 3-D, which became a recurring theme throughout the segment.) Minute-eaters like Count Floyd were lifesavers.

As time went on, it was getting harder for the cast to keep the studio’s schedule. ITV also had to produce a newscast. Haave says Wednesday afternoons proved especially challenging during hockey season, when the ITV truck would leave early Wednesday with five cameras to film the Oilers’ games. Meanwhile, the remaining cameras would be used for news, which baffled NBC executives who’d never seen anything like it in L.A.

“We’d say, ‘Come on! We have to finish this scene,'” recalls Flaherty. “They’d say, ‘Why? We’ve got the Oilers? We’ve got to shoot them. Hockey! Hockey!”’ But if filming couldn’t be done, the cast could still brainstorm and write.

Initially, all of the cast members performed double duties as actors and writers, but when their schedules became difficult to manage, Thomas assigned extra writers to help flesh out ideas, particularly Candy’s.

Candy was the audience favourite. He was a brilliant comic, a bona fide ideas man and a talented actor, who later starred in many films, including Trains, Planes & Automobiles and Uncle Buck, until his death in 1994. But one thing Candy was not was a disciplined writer, says Thomas. “He would spout off more funny ideas in a day that ended up just getting forgotten or lost than the rest of us combined.”

So, Thomas assigned extra writers Doug Steckler, John McAndrew and Bob Dolman, largely to follow Candy on errands. Thomas told them: “He’ll take you to pick up his cleaning, he’ll end up buying something in the sporting goods department, he’ll run out of money, you’ll have to cover him, and then we’ll straighten it out. But follow him around and write down everything he says.’ And that’s the way we got material out of John.”

Candy’s impressive grasp of mimicry made for some uncanny imitations. In one skit he played Julia Child taking on Mr. Rogers, played by Martin Short, in a boxing match. In another, he imitated Beaver Cleaver with impeccable child-like speech patterns and body movements.

Haave says that, at one point, he’d heard rumours that NBC might want to move the show to L.A., to be more like the Friday night equivalent of Saturday Night Live. The producers were surprised by the response of NBC executives when they asked about the rumours. Haave recalls them saying it be a huge mistake because “the show gives a perspective on comedy that comes from outside the country. And people just don’t see things that way when they’re apart of it.”

But, alas, in 1982 the show moved back to Toronto. “The success of the show, the increased production facilities and time required to produce the later series, and the improved income from having sold the shows to U.S. networks, changed the dynamics and made it realistic to move the show back to Toronto,” says Haave.

But it was difficult to maintain the momentum of the show. “Everyone at one point or another showed signs of burnout,” says Thomas. And many of the actors started leaving for other opportunities. By the time the final season rolled out, only four original full-time cast members remained: Flaherty, Levy, Short and Martin.

NBC aired SCTV until 1983, when the station wanted to move the show to a slot on Sunday evenings, according to Thomas. But the crew didn’t want to change the show to abide by the rules of being on a Sunday night. Cinemax picked up the show in the U.S and Superchannel aired it in Canada, cutting its time to 45 minutes. Old skits were circulated along with new material and within a year the show was cancelled.

But, Thomas says, without its time in Edmonton and the support of people like Allard and Holtby, the show would have ended back in ’79. Having a crew work from a place like Edmonton meant they were not only focused on their work, but had a unique perspective.