With the start of the show a few minutes away, Colin is suddenly, debilitatingly exhausted. We just hauled in drums, guitars and amps from our cars parked outside this rundown northside bar. But Colin didn’t. He hasn’t had the strength to do that for years now. The walk to the stage alone has left him collapsed in his folding chair — now necessary for every show. His guitar sits at his feet, his right hand rests atop an aluminum cane planted in front of him. I ask Colin what he needs. He raises his other hand gingerly from his knee, a gesture meant to reassure me. It doesn’t.

“Just a bit of time,” he says.

I get him a glass of water and return to setting up, stealing glances. Colin looks confused, even mildly angry, the resentment probably aimed at the disease that’s doing this to him. I check the time but it doesn’t really matter what it says. The truth is, time’s running out.

We’re both around 50, Colin and I. So are the other members of our band, Daughters of England: Guy, the drummer, and Brock, the bassist. Too old to have just released our debut album, and definitely too old to be performing it live around town. We could be dads to most of the musicians we’ve played with.

But we have to perform. I’m convinced destiny is at play here. Why else would we still be doing this if it wasn’t? Frankly, it’s silly for guys our age to play at being rock stars, to entertain dreams of headlining festivals with legions of screaming fans. But I believe we’re obligated to acknowledge that, a long time ago, because of the history that Colin and I share, we were put on a path to at least try, however remote the possibilities would be.

Colin and I have been friends since eighth grade, quiet suburban kids bonding over grunge music when we should have been focusing on trigonometry. We begged our parents to buy us instruments so we could make sounds like the Smashing Pumpkins or Dinosaur Jr. They did, and then we grew up playing together.

Musically, Colin grew up faster, often in awe-inspiring, even irritating ways. While I struggled with fretting basic chords, he was mastering the fundamentals of soloing. He insists it was because he loved the challenge of figuring out a riff. “It made me feel like I was actually good at something,” he tells me all these years later.

But that’s too characteristically modest of Colin. I have another theory. I believe that music was part of his DNA, like a dormant gene. And when he touched his first guitar, a gene flipped on like a switch on an amplifier.

DNA, however, is also the problem. Alongside the genes responsible for his talent were those that would lead to its undoing. Colin has Kennedy’s disease, an adult-onset loss of neurons in the spine and lower brainstem that slowly weakens all muscles. It’s extremely rare. Maybe 30 people in Edmonton live with it. There’s no known treatment.

If there’s an upside, it’s that Colin doesn’t have amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease), which is fatal and was his initial diagnosis around 2007. He lived with that grim news for two weeks until a second doctor caught a facial twitch — one of few differentiating symptoms between Kennedy’s and ALS — and lifted his presumed death sentence. He could grow as old as any of us. The question is, will he be able to enjoy it?

Colin already lives in sharp contrast to his youth. In high school, when not playing guitar, he’d ride freestyle BMX or ace me on the tennis court. He’d easily push 15-rep sets of bicep curls with 25-pound dumbbells. “Now I can only do three to five pounds,” he says, which he does to battle muscle atrophy. He’s told his muscles are weakening at a rate as high as five per cent a year. He thinks his strength is less than half what it was in his 30s, before the first signs of the disease.

There are other symptoms, too, though Colin is less inclined to reveal if he’s experiencing them. Sufferers of Kennedy’s, who are primarily men, may have trouble swallowing. They can experience a loss of basic sensation and reflexes. Testicular atrophy and a decrease in the masculinizing effects of testosterone can give way to the influence of estrogen.

What’s for certain is that it will eventually take Colin’s ability to play guitar.

“I think I’ve got a good couple of years before my hands start giving me real problems,” he says. The tradeoff in the meantime, Colin adds, wryly but not wrongly, is “there’s a possibility I could grow boobs.”

During the pandemic, I realized that I’m a songwriter the way a framer is a house-builder. I can rough things out and get the studs positioned, but I can’t really make a place where people would want to spend time.

For years, my bandmates and I would meet weekly in a rehearsal space above a central Edmonton pawn shop. We’d joke and jam and drink beer and write.

We let it go during the lockdown, leaving behind almost everything we made there, ghosts of songs I now hope haunt the place. A few weeks after the lockdowns started, loneliness drove me out to the garage with an acoustic guitar. Soon enough, I was writing new songs. But they were incomplete somehow, inhospitable. They needed Colin.

Swept up in the now-or-never aftermath of COVID, I asked if he’d consider preparing them for a studio.

His only question was, “Why didn’t we do it before?”

I think I know the answer: the moment you truly understand what it will mean to lose something is just before it’s taken from you. It’s a tragedy of being human that we’re incapable of preparing for such permanence. Or maybe the tragedy is mine alone. No matter what I know is coming, I’ll never be ready.

That album, Anomalies, came out in November 2024 — and no, I haven’t quit my day job. There’s been no Billboard charting, no world tour. We’ve had a handful of shows in venues no further than about 100 kilometres from home, a few songs on listener-supported radio, a single positive review in a local zine. That’s all. But the album makes me feel like we accomplished something just the same. Colin built homes out of the shacks I made, places where a listener could live comfortably for a few minutes of their lives. But more than that, he gave me, and the world, a record of his talent that will outlive us all.

In return, I want to share his talent as widely as possible — but it’s not that simple. Most promoters aren’t eager to book a quartet of middle-aged musicians with little social media savvy and no real following to show for it. I struggle to align the band’s schedules or ambitions enough to rehearse as often as we should, and I’m constantly juggling the band’s demands with the needs of my own family. The industry doesn’t help either — it’s broken. We’re just a faint whisper in the deafening roar of terabytes flooding music streaming platforms. Still, I feel like I owe Colin a debt I’ll never be able to repay.

If so, Colin has forgiven that debt.

Since the album was released, he believes we’ve done more together than we ever did in the decades previous. For him, it’s not how many shows we play, it’s what happens after each one. People buy T-shirts we had made, some even part with 10 bucks for a CD that they probably have no way of playing. But what stands out most to Colin are the people who approach us after a show to say how much they appreciated the music, that hearing it meant something to them.

“It gives me something to be proud of,” he says. “That’s all I need.”

Which is to say that Colin’s perspective, just like his playing, has evolved faster than mine. Maybe quantity — of shows played or songs recorded or streamed — can’t be the goal. That can’t be controlled. But quality can. Rarely can we choose our circumstances, but maybe we can choose how we see them.

For Colin — for all of us — there’s no need for a Rolling Stone feature or a Coachella slot. Just making the effort to share our music, even with the few who stop to listen, feels like enough. We’ve spent more than half our lives nurturing this talent and our love for it. In that sense, we’ve already “made it.”

Back at that rundown northside bar, Colin rallies in time for the show just like he said he would. He plays every song with fewer mistakes than any of us. He breathes life into music, and music, it seems, is breathing it back into him.

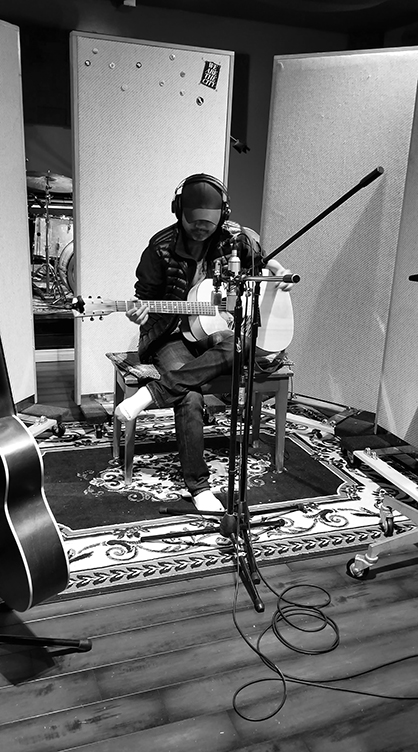

A few weeks later, we’re back at work on new material at Guy’s house, in a room so small I some-times set up just outside of it, poking my head in the door. Colin sits in the corner, improving a sketch of a song I’d brought in. I watch as his fingers find a melody on the fretboard as if it had been there all along. Then, for the first time, I notice his right cheek twitch, a slight and rapid pull and release, like a note bent on a guitar string.

It stays with me for being so ephemeral yet so deeply rooted in something absolute. Is time like that? The whole of it too big to comprehend, leaving us the also impossible task of trying to make sense of a single moment. Here and gone, here and gone, and then just gone.

But for now, at least, it’s here. So we give it our best, playing through a crescendo ending. I think Colin gets that. He hears those moments, and their potential, in our music in a way that the rest of us don’t. “We all keep getting better,” Colin says — and that, he adds, is rare at this point in life. “You’d think there’d be a decline in whatever we do. We’re getting old and tired, but the music gets better. It’s weird.”

That sketch I gave him turns into one of our best songs, a piece about, perhaps ironically, the unabashed confidence of youth — more mature and confident than almost anything on that debut album. In fact, it reinforces Colin’s hopes for a sophomore release, and that, together, we will, in his words, “do this as long as we can.” There’s more music in him, and in us, just waiting.

This article appears in the October 2025 issue of Edify