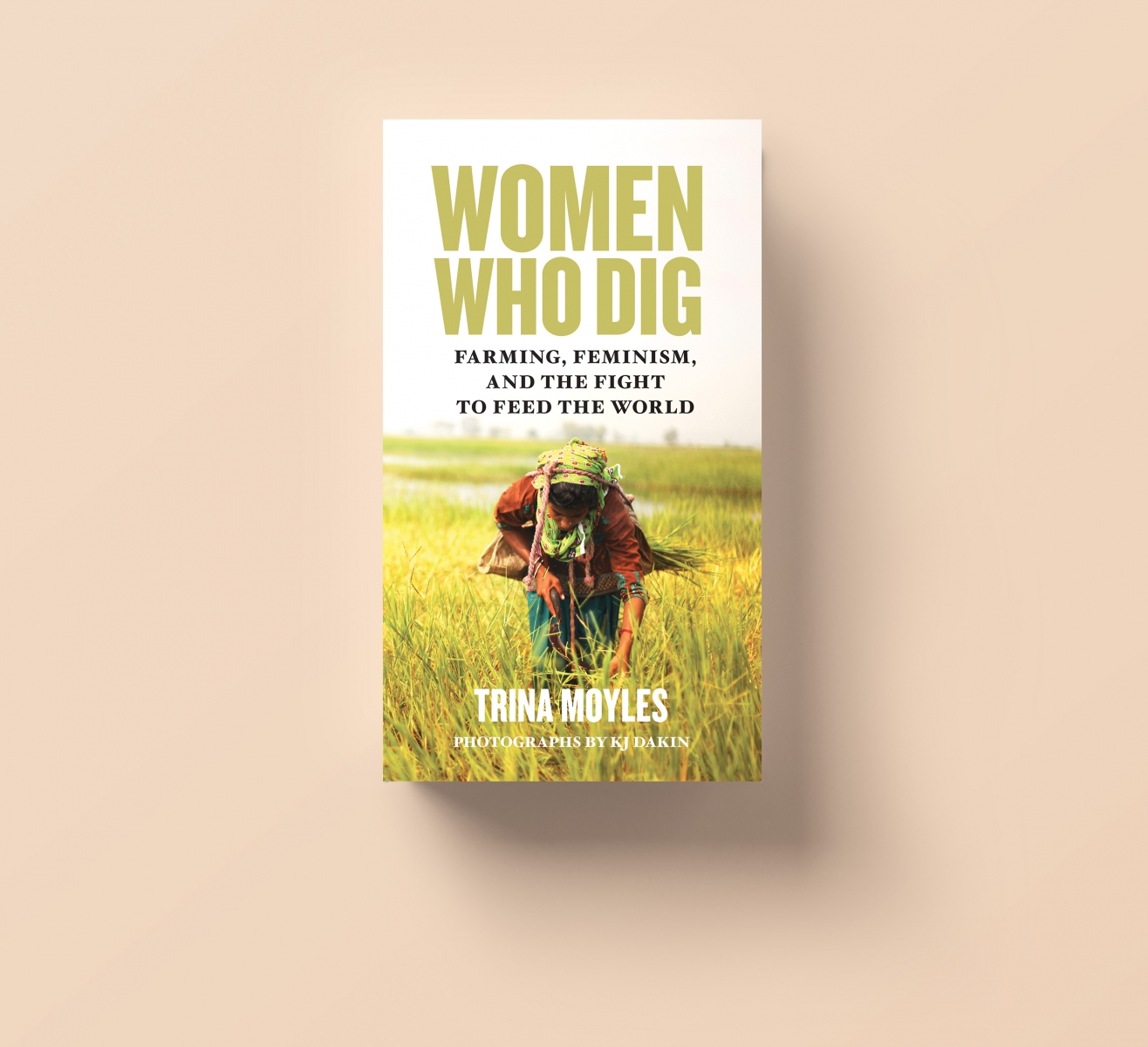

Trina Moyles is a journalist and anthropologist based in Peace River who has spent the past several years dedicating her time to international development. When she moved to Uganda In 2013, she started working on a food-security project that brought her face to face with women farmers. That experience has become the basis for her book Women Who Dig: Farming, Feminism, and the Fight to Feed the World, a travel narrative that looks at farmers from three continents.

Q: Why did you choose to highlight these specific countries for which each chapter is named?

A: I had connections in most of the places that I went [because] it was really important to me to be able to work through organizations that were already doing this amazing, inspiring work with women farmers. I wanted each chapter to sort of focus on a different issue whether it was climate change or how gender-based violence impacts women. I interviewed women in the refugee camp in Uganda to look at how war and conflict displaces farming practices and yet how even someone who has been living in a refugee camp for years is still contributing to the food economy.

Q: What is the connection between farming and feminism?

A: Globally speaking, women tend to be on smaller plots of land, typically growing food crops versus cash crops like coffee. I don’t think they always identify themselves as feminists but they were bearing the responsibility of nourishing their communities – keeping people healthy, getting food to them – yet not getting the recognition. In Uganda they called them abahingi mukazi, which literally translates to “women who dig.” They didn’t see them as farmers because they were growing food by hand and they were on small plots of land so I wanted to change the narrative around that. Other feminist expressions can’t even take place without food; feminists in North America rely on these farmers.

Q: What was the writing process like?

A: I wrote most of the book in Uganda actually, which was quite lovely. I had a garden there and so I would write in the mornings and then in the afternoon go down and work in the garden, weeding. I loved that direct connection between what I was writing about and also having my hands in the soil. I think I realized in the middle of it all I would never write a book like this again. There’s just so much research that went into each chapter and also each chapter felt like it could be a book in itself.