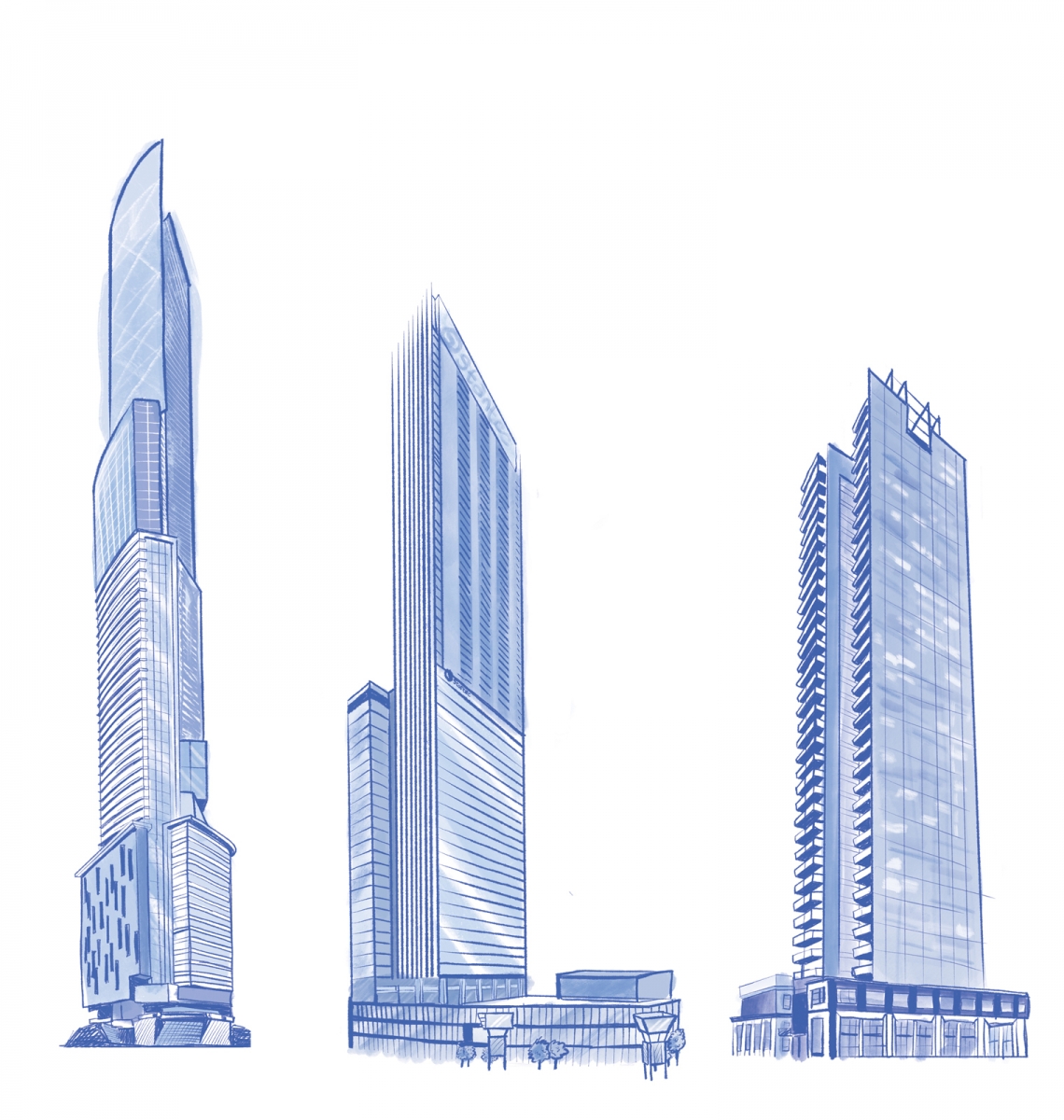

The window of a second-storey boardroom offers a vista of 124th Street. It is filled with nine architects’ renderings of the needle-thin, 80-storey tower planned for The Quarters downtown district, all sitting on stands as if part of a gallery display. Another stand features a shot of the Edmonton Folk Fest site at dusk, looking back towards downtown. But a rendering of the tower has been added, creating a beacon on the east side of the photo. There’s a white scale model of downtown in the centre of the room, which shows off just how high the Alldritt tower will loom over the city.

As I wait for architect Brad Kennedy to arrive, I soak in the views of a project that might end up being just as talked about as the downtown arena. I feel like James Bond, awaiting my quarry in an opulent mountaintop lair, as I look over his plans for world domination.

The planned Alldritt tower is designed to soar 80 storeys into the sky. For those near the top, looking down towards the River Valley, it will feel closer to 90 storeys or more. On December 21st, the shortest day of the year, when the sun is lowest in our sky, Kennedy estimates that the tower’s shadow will stretch for – get this – 2.4 kilometres.

If built – Kennedy and the developer have a 10-year development window to get the mixed condo, hotel and commercial complex done – it will soar above the ICE District’s Stantec tower, currently under construction next to Rogers Place. That project is planned to be 66 storeys.

Condo and commercial projects have transformed Edmonton into a city of cranes. The closing of the downtown airport means that city council and administration no longer have height restrictions to consider when voting on proposed tower developments. But, a 66-storey tower followed by an 80-storey tower – are we looking at a race to the top like we saw in New York City in the early 20th century, when architects and builders turned height into a competition? Where opulent spires and needles sprung from the tops of skyscrapers, just so their landlords could claim they were higher than the building just across the street?

“I don’t think we’ve been as artificial as the spire and what we’re trying to do to get that number in the book,” says Kennedy. “I can’t speak for Stantec and I can’t speak for some of the other projects that have gone out with taller numbers…I don’t know if a race to the top was the primary goal, but I do know it is something that Edmontonians are starting to talk about. I find of the dozen re-zonings we’ve done on towers in the downtown, from Pearl to Icon to Fox to Symphony [all condo projects] , this is the first one where we’ve had people who are completely unconnected with it saying on social media, ‘hey we’re a big city now.’ There’s something about it. There’s an energy to say we’re as tall as places like Seattle and Chicago and Miami. We’re taller than many of those big U.S. cities with a tower like this. It’s an interesting feeling because people are no longer like, ‘hey we’re a grown-up version of Red Deer.’ It’s not about how great and exciting we are, but isn’t it exciting that we’re growing up?”

WHY SO HIGH?

Kennedy says that the Alldritt tower wasn’t designed to set a record as Edmonton’s tallest building, and as Canada’s tallest building outside of Toronto. The project soars to 80 storeys, Kennedy says, not due to hubris of the architect or the developer, but because of economics.

The east side of downtown, from Jasper Avenue moving downward into the River Valley, presents a challenge for developers and builders. Years ago, that area of town was filled with gas stations and dry cleaners, which contaminated the soil. And an abandoned mine – Kennedy says that tests have shown it has collapsed – is buried 45 metres underneath the surface. So, no matter the project, a significant amount of geological work has to be done to stabilize the site for construction. To make that pay back, a building needs to be, well, awfully big.

The project could have been shorter and wider, but Kennedy says that profile would have blocked more downtown views and blotted out the historic buildings on Jasper Avenue to someone looking on from the south. A taller, narrower, transparent building allows the developer to realize needed revenue-generating square footage but, in Kennedy’s opinion, also allows for the least disruption to the downtown view.

“One of the key factors in this Alldritt hotel and residence is the foundations below this tower are the same for a 40-storey building or an 80-storey building,” says Kennedy. “So, there’s an incredible investment that needs to go subsurface, due to the mine, due to the slide, due to the retaining of the bank, due to the former environmental conditions. So, there is a considerable economic advantage to going bigger.”

The foundation for the Alldritt is estimated to be 75 metres deep, going right through the old mine. To stabilize the ground, before drilling begins, low-compression concrete will be injected down into the old tunnels, filling up the cracks and crevices.

WHO IS GOING TO LEASE ALL THE SPACE?

The Stantec project, new hotels and condo towers have all insulated Edmonton somewhat from the economic slowdown that’s kicked the rest of the province in the ankles. But, with floor after floor of new office and living spaces being stacked atop each other, will this create the kind of crippling vacancy issue that we’ve seen in Calgary? Do we simply have enough businesses to fill up all the new space?

Jimmy Shewchuk, the business development manager at the Edmonton Economic Development Corporation, says that Edmonton’s current commercial vacancy rate is at 15.1 per cent. New buildings will put even more pressure on that number. For a healthy balance between market rate and opportunity, the vacancy rate would be at about 10 per cent, which means most of the spaces are utilized, but there is enough space to not put huge upward pressure on lease rates.

Shewchuk says the Stantec tower and the 25-storey Enbridge Centre, which opened in 2016, are considered “AA” office buildings. They are attracting marquee clients who had previously leased elsewhere in the city, in what are considered “A” or “B” level properties. “These projects had people flocking to quality, and they showed what the market was starving for,” says Shewchuk.

But, as these new buildings fill up, the landlords of the older properties will look for new ways to attract new tenants. That means better lease rates, better long-term options, some needed renovations and possibly repurposing of some of the older commercial spaces.

“They have created an opportunity to invite some new businesses downtown,” says Shewchuk. “New businesses will look at downtown and see it as a viable option.”

Shewchuk believes that new types of businesses, whose owners realize they don’t need main-street frontage, can thrive on floors of these older office buildings. Fitness clubs, daycares and medical offices could replace the law firms, energy companies and accounting services.

“The real question is: Who is worried? The market dictated that we needed new buildings. We’re transitioning from Big Little City to Little Big City.”

CONVERT OR ATTRACT?

The issue of rising vacancies was tackled by the Downtown Business Association (DBA) in the fall of 2016 when it hosted a talk by University of Alberta student Satish Narayanan, who presented his research on cities that have successfully transformed vacant older office towers into residential and mixed-usage spaces. He talked about a vacant office building in Amsterdam that was converted into a mixed-use building with student dorms and a four-star hotel in the same building. The students staying in the dorm subsidized their costs of living by working at the hotel.

Jim Taylor, DBA’s head in 2016, said he understands that some of Edmonton’s office towers would be difficult to convert, so there is a need to bring new tenants to these buildings when the old tenants move to the gleaming new towers.

“It’s converting out-of-towners to downtown,” says Taylor. “I think the most modern of the office towers would be the hardest to convert, just because of their structure and size. Those might be the buildings where we encourage young firms to come downtown and move into.”

PRIDE AT ITS HEIGHT?

As a whole, we’re obsessed with height. Many of us can name the tallest buildings in the world. Even a person who’s never been to New York City knows about the Empire State Building. Same goes for Toronto and the CN Tower. The Burj Khalifa in Dubai is a modern wonder.

So, no matter if we’re building upwards because of pride or density, tall buildings like Stantec and Alldritt have certainly stirred up the passions of Edmontonians – both positively and negatively. When it came to council in April, Alldritt passed by a narrow 7-5 vote. Mayor Don Iveson cast a nay vote. When asked about it, Kennedy gives a wry smile and simply says, “it’s election season.”

Kennedy says the 36-storey Pearl, the condo tower which looms over Oliver, was transformative for Edmonton, and he expects the downtown projects to do the same.

“What I’m interested in about being an architect in Edmonton right now is I think Edmontonians have started to say ‘what’s possible?’ They’ve stopped worrying about some of the issues that some of the other bigger cities are long past concerned about.”

Kennedy thinks that Edmonton has been “insecure about height” for a long time, and that projects like Alldritt tower are “game changers.”