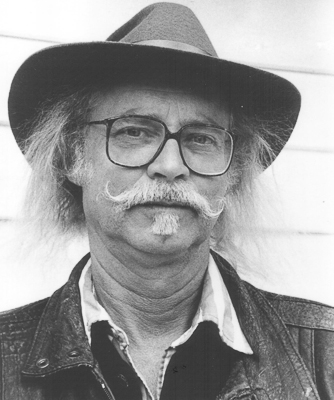

It’s hard to know what W.P. Kinsella would have thought of it all: Yankees slugger Aaron Judge taking a mighty swing and launching a ball into the Iowa night sky. Or, maybe, the sight of White Sox shortstop Tim Anderson rounding third and heading for home under the glare of the lights.

Would the Edmonton-born-and-bred Kinsella been thrilled about a real Major League Baseball game, one that counts in the standings, being played not in a metropolitan stadium of concrete and glass, but on a diamond hacked out of an Iowa cornfield? All in honour of a story he wrote nearly four decades ago?

Kinsella had a long and controversial literary career before he died in 2016. But, there’s no arguing that Shoeless Joe, his most famous work, has endured. The story is known to baseball fans who have never even opened the book — it tells of the ghosts of Major Leaguers past who gather in a diamond hacked out of an Iowa cornfield, and rekindle their love for the game.

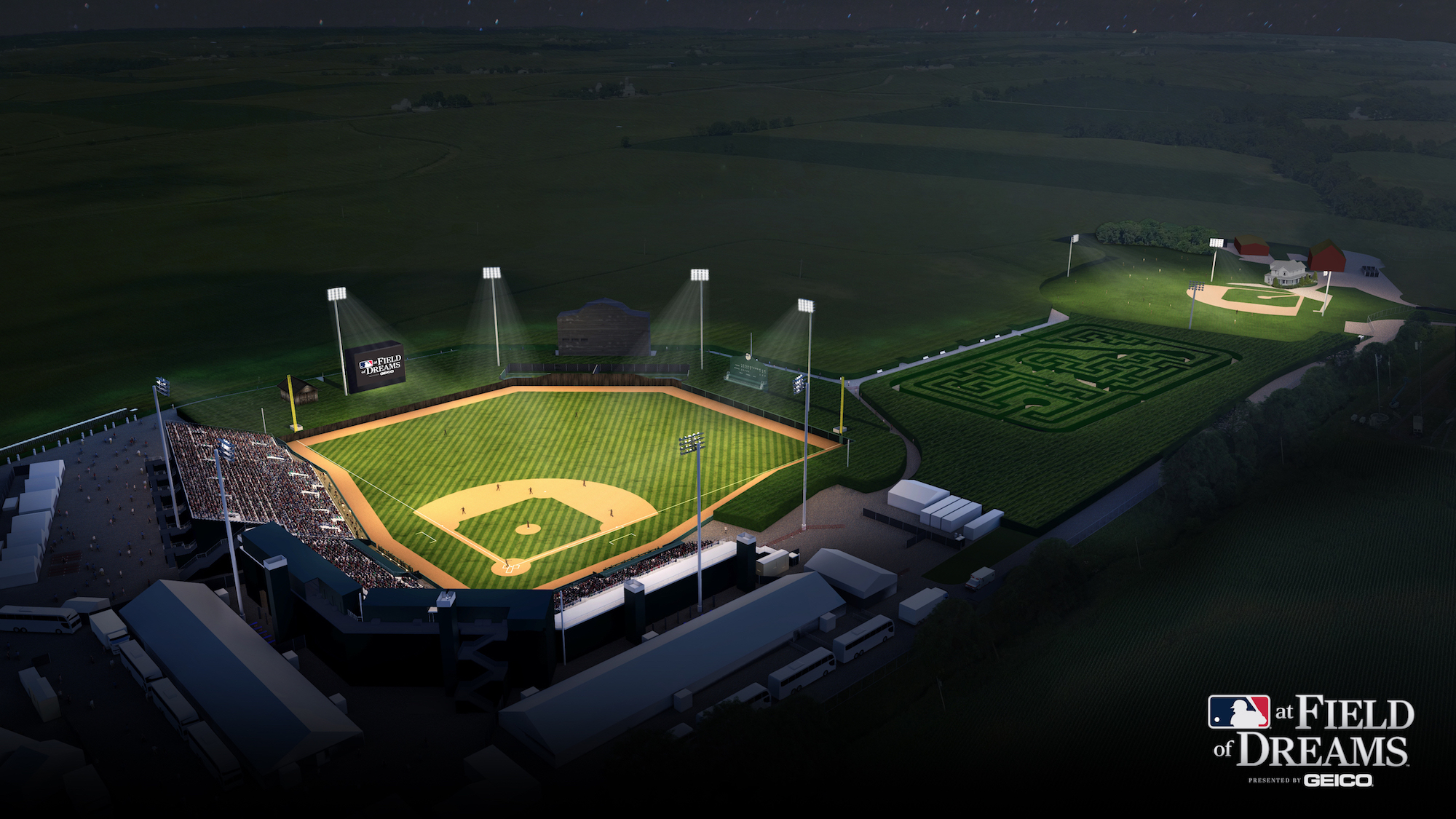

The book became the 1989 film Field of Dreams, maybe the most famous baseball movie of them all. And, to honour that great slice of Americana — written by a Canadian — Major League Baseball is staging a Field of Dreams game between the New York Yankees and Chicago White Sox in Dyersville, Iowa on August 12, a made-for-TV celebration of a story hatched from the mind of an author who spent part of his childhood at Edmonton’s Parkdale School. (He wrote about his time at Parkdale for this very magazine, shortly before he passed.)

In fact, Kinsella wrote many stories about baseball. In 1991, the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame awarded Kinsella the Jack Graney Award for his lifelong contributions to the game.

MLB’s brass has confirmed that Kinsella will be honoured during the game — a unique connection between Edmonton, Iowa and Major League Baseball. A “Dreamer” segment will be shown on the sideboard during the game that will include facts on Kinsella and others who were instrumental in making the event happen. Kinsella’s Canadian roots will be acknowledged.

“We are thrilled to host MLB at Field of Dreams in Dyersville, Iowa, marking the state’s first-ever Major League game,” says Jeremiah Yolkut, director of special events for Major League Baseball. “As we celebrate the movie’s meaning to generations of baseball fans, we also remember W.P. Kinsella’s novel Shoeless Joe. Both the book and the film highlight our game’s generational appeal and bring together the baseball fans of the United States, Kinsella’s native Canada and beyond.”

In a 1996 interview shortly after the release of If Wishes Were Horses, a book that united itself, Shoeless Joe and The Iowa Baseball Confederacy as a loose trilogy about baseball and magical realism, he told me this: “Baseball has always given me what I’m looking for as an author. Take a look at hockey, even Wayne Gretzky isn’t capable of doing anything and everything.”

Without a clock, with lines that separate at home plate and continue on and on, baseball has the potential to be infinite. Remember that hitting a ball over the outfield fence is only a home run if it lands — if, by some miracle, an outfielder leapt over the fence and caught the ball in the stands, it’s an out. And Kinsella was the author who may have understood the magic of baseball more than any other.

“I have to decide if I want to bench a certain character, save characters for later or have the character swing away,” he told me.

So why aren’t we sure what Kinsella would have thought of a game that’s been created in honour of a story he dreamed up? Like the author himself, it’s complicated.

In 1996, Kinsella told me he’d sworn off Major League Baseball — he’d said that the labour stoppage that led to the cancellation of the 1994 season had turned him off the bigs. It was a season where the Montreal Expos had been the dominant team before the stadiums went dark. Had the Expos gone on and won the World Series that season, it’s a reasonable argument to make that the franchise would have survived — there would have been no move to Washington, D.C. Canada would still have two Major League teams.

So, if he was alive today, would he have accepted an invite to go to Iowa for the game? If how he lived his life was any indication, the answer is… maybe?

Shoeless Joe was first published in 1982: it was an extension of the short story, “Shoeless Joe Jackson Goes to Iowa.” In the novel, Ray Kinsella is instructed by a supernatural voice to “build it, and they will come” in a cornfield not too far from where the author had attended the famed Iowa Writers’ Workshop. The ghosts of baseball legends, who can only be seen by mortals who believe in the magic of the game, play night after night. But central to the story is the ghost of Shoeless Joe Jackson, the baseball legend who was banned from the game for life after the 1919 “Eight Men Out” scandal.

For those of you who aren’t baseball-history buffs, it went like this; a large number of Chicago White Sox players had agreed to throw the 1919 World Series, and Jackson was implicated. Jackson later confessed to being part of the match-fixing scheme, but then recanted and maintained his innocence till his death. Baseball historians have suggested that Jackson’s illiteracy may have played a part in his confession. But his stats bore out his claim of innocence — he led the World Series in hits. (His batting average in the World Series was .375, even better than his .351 regular-season mark.) Even today, there are those who believe Jackson should be posthumously reinstated into Major League Baseball and delivered to baseball’s Hall of Fame.

The novel was not universally loved. From Kirkus Reviews: “A sweet, imaginative fantasy — but, unfortunately, one doesn’t need to know this first novel’s publishing history to recognize it as a short-story that’s been fatally overextended. The Peter-Pan-ish theme wears thin, drifting from goodheartedness into simplemindedness.”

But, in Canada, the reaction to the story was celebratory. Shoeless Joe took the Books in Canada First Novel Award and the Canadian Authors Association prize. But it didn’t quite launch Kinsella into the stratosphere of Canadian literature, either.

Kinsella’s life was a maddening collection of contradictions. Loved and hated. A maverick, but a man who wanted to be accepted and loved as a true man of letters in his home country.

While many of his baseball stories were set in Iowa, where he studied, Kinsella’s writings about Canada didn’t come in the form of baseball books, but in a series of comic stories with Indigenous characters. And, in the 1980s, he was lauded for it. The Fencepost Chronicles won the Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour. The stories were the basis for a movie and the CBC series, The Rez.

It wasn’t until the 1990s till Kinsella’s stories were cited as examples of cultural appropriation. And his reaction was to be anything but apologetic. He and Alberta literary giant Rudy Wiebe refused to be in the studio together for a CBC debate on the topic; Wiebe had become a vocal critic of Kinsella’s stories about the reservation, despite the fact that Wiebe himself was not Indigenous. A cynic would have pointed out the folly of two white Canadian literary voices at odds about how Indigenous people were portrayed by, well, white writers.

As well, Kinsella began an affair with Evelyn Lau, a writer three decades his junior. She would eventually publicly humiliate Kinsella with a Vancouver magazine essay that described his feeble, aging body in rich, lurid detail. A year after his death, his book based on that failed relationship, Russian Dolls: Stories From the Breathing Castle, was published. But, is a last word really worth anything when it comes from the grave?

Kinsella, in true Western Canadian maverick fashion, became politically engaged in the 1990s, appearing at Reform Party meetings, and offering his voice to their campaigns. It was almost as if Kinsella enjoyed affiliating with anything that the majority of the Canadian literary scene would have found distasteful. The RPC spoke to the stereotypically Western Canadian value set that Kinsella espoused; he hated religion, or organized anything. He was a staunch libertarian. The fact he found such joy in writing about a team sport is another irony. But baseball is a unique team sport in that it’s made up of one-0n-one battles; pitcher vs. batter.

If Kinsella were a ball player, he would have been the foul-mouthed veteran who got tossed out of games for arguing balls-and-strikes calls; he would have been comfortable on a team of rogues, like the Pittsburgh Pirates of the 1970s, who often brought together players considered too problematic for other teams.

But, even the most maverick ball player wants to win the World Series. And, as much as Kinsella liked to portray himself as an outsider, much of his bitterness came from the fact that he simply wasn’t accepted as a part of the serious Canadian literary scene. Did he long to be considered alongside the likes of Robertson Davies or Mordecai Richler? Senator Paula Simons, who profiled Kinsella for Alberta Report in 1988, thinks so.

“He always liked to see himself outside of the Canadian literary camp, but that isn’t true,” she says.

In fact, because Shoeless Joe and so many of Kinsella’s baseball works use magical realism, which wasn’t uncommon for prairie writers in the 1980s, Simons argues that his works are an advertisement to how much he belonged to the Canadian literary scene. He may have acted the part of the outsider — but, like Kevin Costner in the film version of the book, he was playing a role.

It’s also worth noting that, early in the 21st century, he judged the Books in Canada First Novel Contest.

It really is amazing how people who write for a living are so often misunderstood. But Kinsella went out of his way to be misunderstood.

Baseball has a long history in Edmonton. Sure, many of us can still remember the Trappers teams that played in the Pacific Coast League, and were AAA affiliates to the Montreal Expos, California Angels, Oakland Athletics, Minnesota Twins and Florida Marlins, to name a few. Players like Devon White and Ron Kittle played in Edmonton. Canadian slugger Matt Stairs played here, as did Dante Bichette, who would go on to become an MLB all-star and is the father of current Blue Jays phenom, Bo Bichette. The Edmonton Trappers won four Pacific Coast League titles — 1984, 1996, 1997, 2002.

RE/MAX Field is one of the hardest parks in the world in which to hit a home run. “The Other Green Monster,” located 42o feet away from home plate, rises 30 feet high in centre field.

But, let’s go back even further. After the Second World War, there was a glut of elite baseball players across North America. Players were returning from combat, adding to the young phenoms coming out of colleges and prep teams. There weren’t enough minor-league teams to stash them all.

Enter the Intercity League, a four-team semi-pro circuit, with two teams in Edmonton and two in Calgary. And, to keep them away from the prying eyes of scouts who patrolled the minor leagues across the United States, the Brooklyn Dodgers used the Alberta teams as places to stash some of their prospects.

Glen Gorbous played in Calgary, was in the Dodgers system, and would later play for the Cincinnati Reds and the Philadelphia Phillies. He would also set a Guinness record for the longest throw of a baseball, at 445 feet, 10 inches.

The Edmonton Eskimos (Ed. note: We are using the team’s racially charged name in the first mention because it’s historical fact — and we can’t gloss over the fact that this nickname was commonplace in this city’s sports scene at the time) were led by Bob Lillis, who hit over .400 in the Intercity League; he’d go on to play for the Dodgers, St. Louis Cardinals and Houston Colt .45s (who later became the Astros).

As a teenager, Eskimos’ team owner John Ducey brought in Allan Wachowich to be the bat boy. Wachowich would later become the chief justice of Alberta’s Court of Queen’s Bench.

“When I became the bat boy, it was really a big honour because it was an envious position with all kids my age in the city,” says Wachowich. “It was a pretty old building and I had to try to keep the clubhouse neat and clean, which was very, very difficult. I’d come early and hang up all the uniforms, line up the spikes, shine all the spikes. My brother taught me how to shine shoes so that was somewhat easy. I became somewhat of a favourite to a lot of the people there.”

While many of Kinsella’s baseball books were set in Iowa, you have to wonder where Kinsella’s life-long love of baseball was stoked; was it in this city? And, well, the comparison between the Canadian prairie and the American plains is a pretty easy one to make.

It was in If Wishes Were Horses, that his hometown got a mention, with Kinsella’s tongue firmly planted in his cheek. The book came out when Edmonton still had a team in the Pacific Coast League. When the book was published, the Trappers were affiliated with the Athletics, but had just recently had their affiliation with the Angels ended. It’s safe to say that, during the writing of the novel, the Trappers/Angels affiliation was still a going concern.

In the book, a character from the fictional Caribbean dictatorship of Courteguay refers to Edmonton, without actually mentioning the city’s name.

“I, Hector Crucible, have signed a contract with your California Angels. I am to be assigned to a team in Canada, where I am told there is ice in the outfield all year round.”

On August 12, there certainly will be a lot of talk that day about how baseball is the great American game, and how Shoeless Joe and Field of Dreams reflected that.

But, will anyone in an Edmonton sports bar, with the game on the tube, tip his or her cap when the first pitch is thrown? Because, there is no game in an Iowa cornfield if it wasn’t for a kid from Edmonton who allowed his love for baseball to influence so much of his writing. I am not a religious man, but I’d like to believe that the ghosts of Kinsella and Shoeless Joe will take in at least a few innings, and maybe Jackson will confide if he really was guilty or not.