Starting with the arrival of the continent’s first Muslims during the transatlantic slave trade, Mouallem details the history of a faith that played a part in South American slave revolts, Midwestern manufacturing booms and a battle for the heart of the Caribbean. Mouallem also comes face to face with Islam’s still unfolding story in the Americas, which includes puzzling run-ins with a long-forgotten sect of Black mystics, a peek into a radically progressive secret mosque, and the response from Edmonton’s Islamic community following a 2017 attack near Commonwealth Stadium. The picture that emerges from Mouallem’s collection of interviews and vignettes is of an Islam that is far too diverse to ever be captured in a three-minute news segment, but also of a faith that can be incredibly regular.

“There was a need to normalize Islam and normalize Muslim people in the West,” he says. “I hope [Praying to the West] accomplishes two things. One, I hope it will help other people from Muslim backgrounds to feel more of a sense of belonging and entitlement here and less of a sense of alienation. To feel like they have always been a part of the story and to rediscover a bit of themselves through the rediscovery of Islamic history. And, I also hope that by revealing the long Islamic history of the West, it would help quell people’s fears and debunk this notion of Islam and Muslims as this modern phenomenon and cultural invasion. If people understood that it’s always been here, but they’ve been a little bit deceived to overlook it, then maybe that will make them feel more comfortable with their Muslim neighbours.”

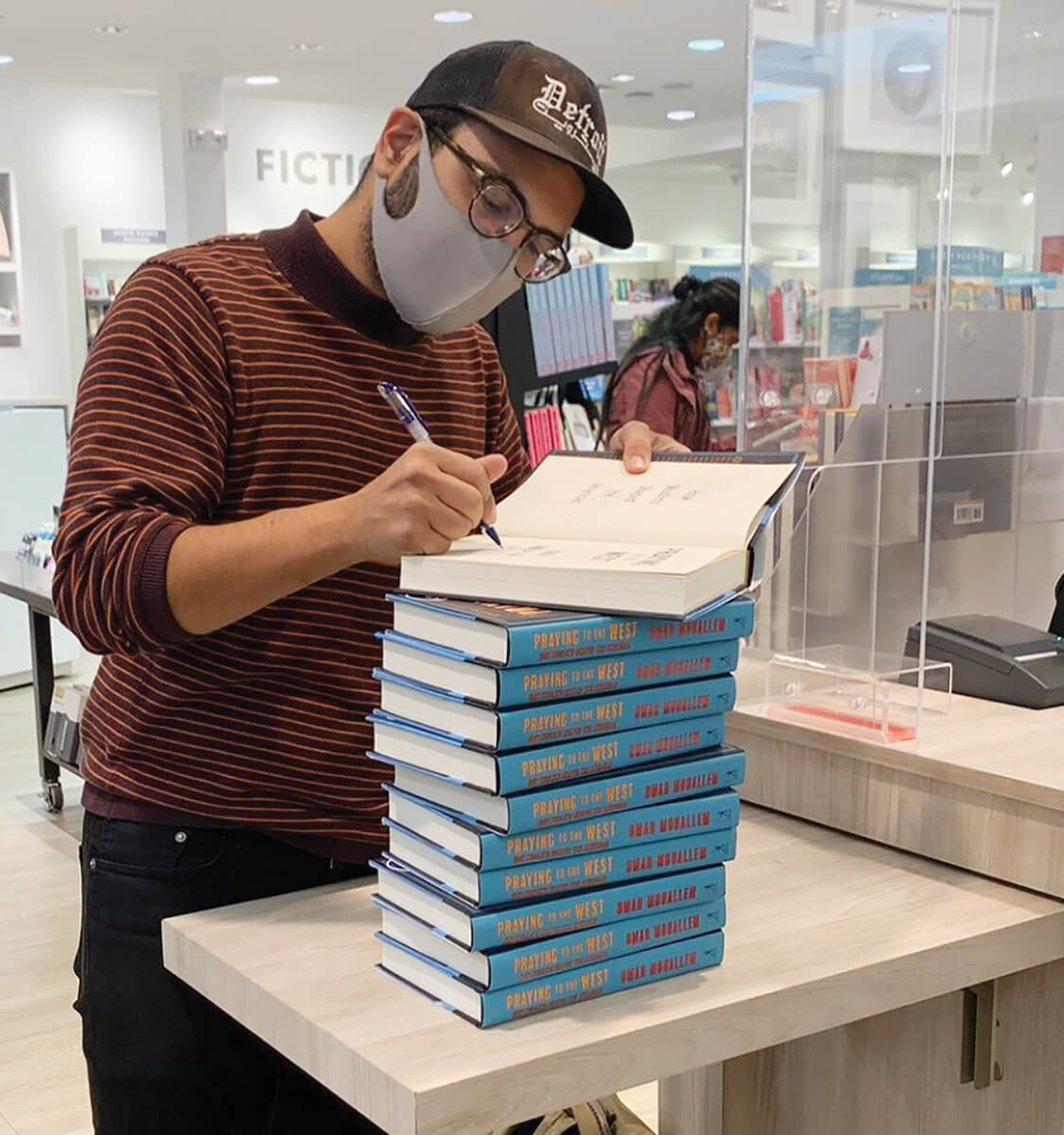

As a self-described lapsed Muslim, Mouallem’s own struggle with identity is documented Praying to the West, as he reacquaints himself with the religion of his childhood. What he discovers is a faith more beautiful and broken than he had previously thought, which is show-ing signs that it is truly coming into its own in the West.

“The only important thing is, can Muslim people in the West create an environment where they feel like they can worship on their own terms? Shape it the way that they want to and not according to how religious authorities in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Lahore… or Washington think they should be practising? Can they shape it into something that works for them and their micro community? And I think that the answer is yes, more than ever.”

This article appears in the November 2021 issue of Edify