Whenever I give an interview or talk about my two crime novels – Fall From Grace and A Killing Winter – something inevitable happens: I’m asked why I set my novels in Edmonton.

Normally, I give a stock answer, noting that since I was born and live in Edmonton, it would make more sense to set my books here, rather than New York, Los Angeles or even Minneapolis.

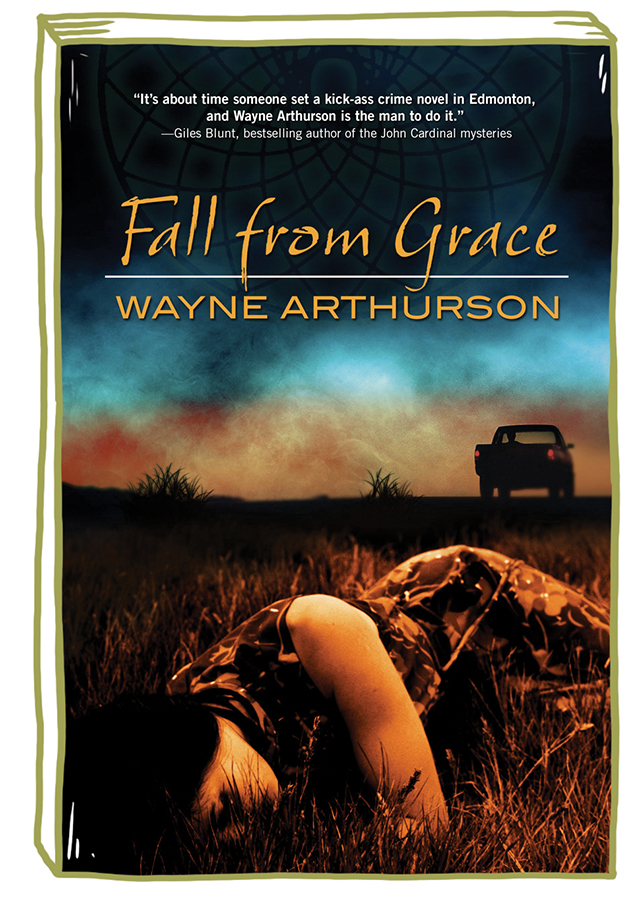

The first novel in my crime series, Fall From Grace, opens with a dead body in a field outside the city. This was done for a reason. Edmonton has had its share of dead bodies found in fields, most of them female and many times aboriginal. So I wanted to draw attention to that.

And while the main character, Leo Desroches, does interact with locales familiar to Edmontonians – the Baccarat Casino, the now-demolished Hotel Cecil, the LRT – I made a point not to focus much on specifics. These places, the restaurants, the clubs, the businesses, are subject to change. Like the Hotel Cecil, which was the site of a major scene in A Killing Winter, written (although not published) before it was demolished. Instead, I focused on more durable intangibles of the city – the weather, the light of the sun in various seasons, the history and geography – to give a more solid sense of place.

“What I loved [about Fall From Grace] were the little observations about Edmonton life,” Ted Bishop, the author of Riding with Rilke: Reflections on Motorcycles and Books, a finalist for the 2005 Governor’s General Award, wrote me one day. “The light at the warm end of the spectrum, the houses with the living room in the front and the kitchen at the back – things I’d absorbed by living here all my life, but never really saw till you pointed them out.”

But, to be honest, the question of “Why Edmonton?” comes up more often than a response like that of Bishop. And I’m disappointed in it, especially if it comes from an Edmontonian. It reflects an attitude that our beautiful and dynamic city doesn’t have what it takes to be a setting for a novel, that the people who live here aren’t interesting enough to become characters in books.

The truth of the matter is Edmonton is a fantastic place for literary works. It’s not a new development; Robert Kroetsch (The Studhorse Man) and Henry Kreisel (The Betrayal) both set their novels in Edmonton at a time when you could count on one hand the number of Canadian publishers located outside of Toronto. The Studhorse Man won the Governor General’s Award for Fiction in 1969.

But there is a growing desire for writers to use Edmonton as a setting for their literary productions. So, I talked to three out of a growing cadre of writers who look to the city, not just as a setting for their books but for inspiration.

The inner city area of Kush, featuring the neighbourhoods of Queen Mary Park, Central McDougall, McCauley, Spruce Avenue, Norwood and Alberta Avenue, is key to the novels of Minister Faust. In his first novel, The Coyote Kings of the Space Age Bachelor Pad, two African-Canadian fanboys battle evil in the midst of these Edmonton blocks. In a review of this book, the New York Times wrote: “Faust anatomizes [the Edmonton setting] with the same loving care Joyce brought to early-20th-century Dublin.”

In The Alchemists of Kush, Faust writes about a teenaged refugee from Sudan who finds his voice in Kush, while Edmonton is a catalyst location for an interstellar war in his fourth novel, War & Mir, Volume 1: Ascension.

“When I watched television as a kid, I saw all these neighbourhoods in older cities that really felt alive. And Kush was the one neighbourhood in Edmonton that had that same feeling. And it really has it today,” says Faust. He calls the area “Kush” because of the recent influx of immigrants from Africa and development of businesses and restaurants to service them, especially those from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Somalia, Sudan and South Sudan.

“You visit Giovanni Caboto Park on a sunny afternoon and you are sitting at a place where you see the beautiful, shining towers of downtown, a beautiful landscaped park filled with folks and families, and old businesses that aren’t chains. It’s a neighbourhood that’s alive in a way that I think the rest of the city deserves to be alive.”

And while Faust believes that writers can and should use any settings they wish, he also believes that Edmonton writers should write more books set in their home city.

“You’re here now, open your eyes. The question shouldn’t be: Why you are writing about Edmonton, but why wouldn’t you write about Edmonton?”

When Janice MacDonald said she was going to write her master’s thesis on sub-literary material, literary types scoffed at her. And when she said she was actually going to write a detective novel set in Edmonton, the scoffing continued.

“And if you do that sort of thing enough to me, I get more stubborn. So it became Edmonton or bust in a lot of ways,” says MacDonald. That novel, The Next Margaret, was published in 1994 and featured amateur sleuth Miranda “Randy” Craig. In the story, someone is killed at the University of Alberta and Randy Craig is thrust in to solve it. The novel set the stage for the subsequent books. Since Randy Craig is connected to the university as a researcher, historian and sessional instructor, all of her investigations are connected to the supposed ivory tower of academia and the neighbourhoods around it.

So MacDonald’s books are packed with bits of Edmontonia, such as seeing Ben Sures play at a small club or Randy Craig ordering food at her fave restaurant, The Highlevel Diner. And because these are mysteries, bodies are sometimes found in specific locales, such as the (gasp!) hill at the Edmonton Folk Fest, which was the case in her 2011 novel, Hang Down Your Head. Or (gasp!) in Rutherford House, the home of Alberta’s first premier, which happened in her more recent novel, Condemned to Repeat. The fifth instalment in the Randy Craig series was published in June of 2013 and spent 16 weeks on the Edmonton Journal bestseller list, with 13 of those weeks in one of the top two spots.

“I can put a fictional body where I damn well please, but I know they were really, really nervous at Rutherford House when they heard it was happening,” says MacDonald, who does research at places before she makes them murder scenes. “But I haven’t heard anything but positive reaction from those folks. In fact, I’ve heard of people inspired by the novel to make their first visit to Rutherford House in years.” (To give it and MacDonald credit, Rutherford House did not ask to vet the manuscript before it was published.)

Using specific and actual locales is essential in detective novels, MacDonald says, because if the location feels real, so will the murders. “When you unpack the whole concept of detective novels, you really need people to buy into a location that other people don’t necessarily know about,” she says. “Which was my bonus because at the time no one was really writing about Edmonton.

“Most readers outside Edmonton don’t go ‘Ooooooh Edmonton.’ But within Edmonton they’ve embraced it as a celebration as well as a series. And I’m all for that.”

Originally serialized in the Edmonton Journal over a three-month period in 2005, and then published by McClelland & Stewart in 2006, Todd Babiak‘s The Garneau Block captured the attention of Edmontonians with his satirical look at distinctive Edmonton characters in the distinct upscale Edmonton neighbourhood of Garneau. Babiak also set his third novel, The Book of Stanley, partially in Edmonton.

But The Garneau Block wasn’t just set in the city, says Babiak. “Edmonton was the main character,” he adds. “I wanted the book to be about the city’s mythology, what it means. So I populated the book with the kind of people that represented Edmonton. I also wanted to set that book in Garneau because I’ve been drawn to that neighbourhood so much that I now live in Garneau. I feel like I’m living in one of the great neighbourhoods of North America.”

The museum shaped like a glass buffalo that appears in The Garneau Block was so inspiring to Creative Writing and Design students at the University of Alberta, that they named their new literary magazine, Glass Buffalo. That salute to his book almost made Babiak cry.

But he admits that some readers complained there was too much of Edmonton in it, making it seem phony.

“We have so much fun saying negative things about our city. In the past we have been the worst ambassadors in the history of ambassadorship,” he says, adding that if you give Edmonton a superficial glance and only look at the power centres, strip malls and industrial zones, you won’t see a place that cares about history, culture or identity.

“But when you do peel it back, you’ll see, as Satya Das calls it, a 21st century frontier. But it’s always been a frontier. And at the moment, it’s an idea frontier. This is a great place to launch an idea.

“Edmonton as a literary microcosm has everything you need to tell. You could write the greatest novel of the 21st century, set it in Edmonton and there would be no problem.”