A young parent’s death is a loss compounded — watching a young parent disappear to dementia before he or she passes is particularly cruel. While surely therapeutic, it could not have been easy to write poetry about her father fading away in his 80s, but, in Cold Metal Stairs, Edmonton’s Su Croll sure makes it easy, even lovely, to read.

In just over 70 poems, Croll takes us on the tragic journey of an adult daughter, with her sister and mother, grieving the loss of their father and husband while he’s still technically alive. While terrifying for all, the excruciating experience is arguably more traumatic for family members helplessly watching their beloved patriarch diminish into nothing — to the point they just wish it would end. In “Releasing the ghost,” she writes, “When my father goes, he will release us from the ghost he has become,” closing with lines about their grief “dovetailing into guilt, at how we long for my father’s death to relieve us of his pain …”

And yet, even from the depth of dementia’s darkness, her words point toward the light, sharing her family’s strength and resilience in a hope-sapping struggle. And the poems don’t end when her father does. “Cold metal stairs” could easily refer to the slow, steady decent into unknowing and death, but the words actually describe the family ascending to the roof of a university building, “where hooded telescopes waited to give us something of the sky,” which appear in “The night after he died,” the opening poem of the second-last section, titled “Flowering into light.”

Once damaged by dementia, the brain can’t heal itself, but in Cold Metal Stairs, Croll shows her mind can comfort others.

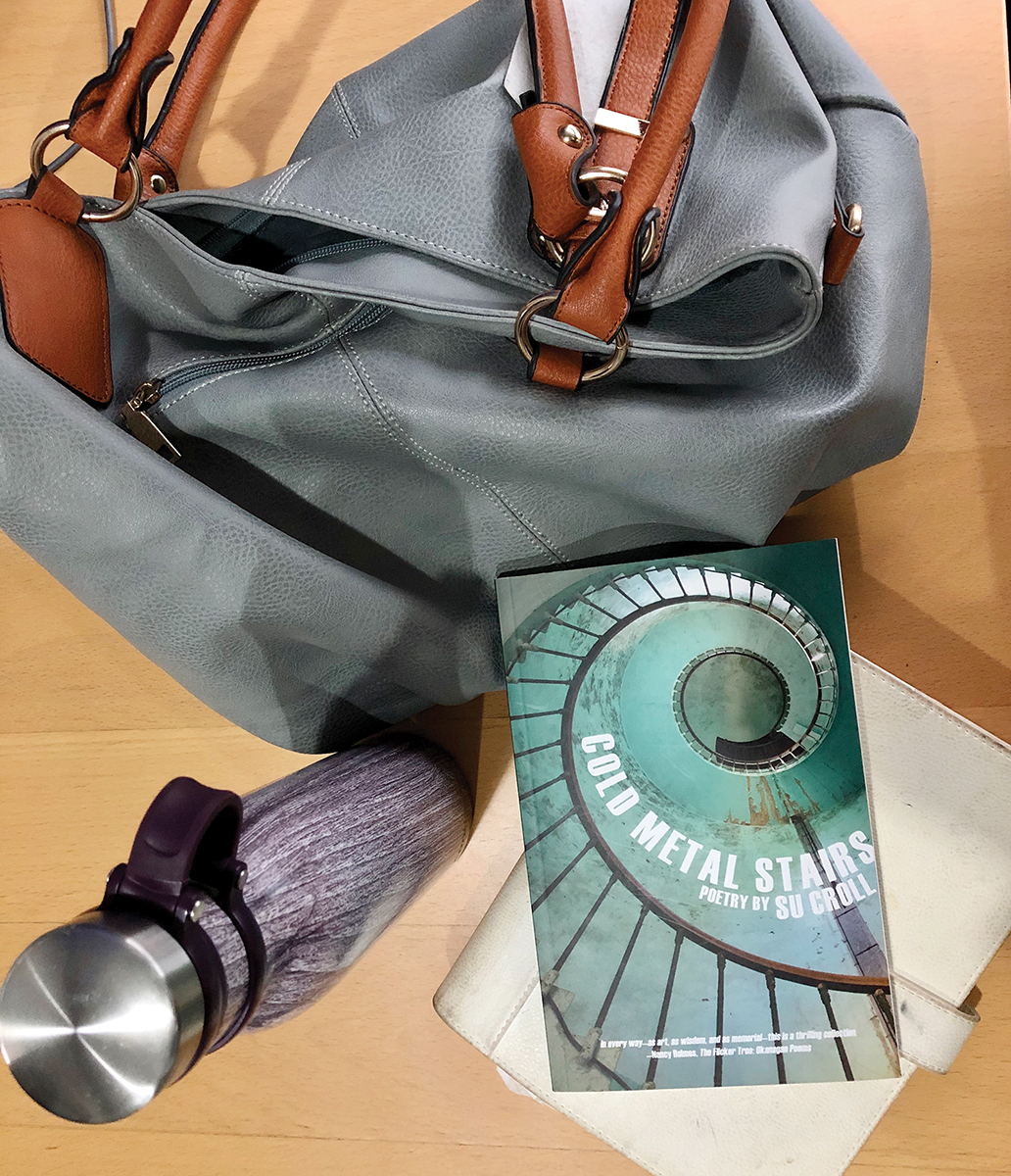

Cold Metal Stairs

By Su Croll, Turnstone Press