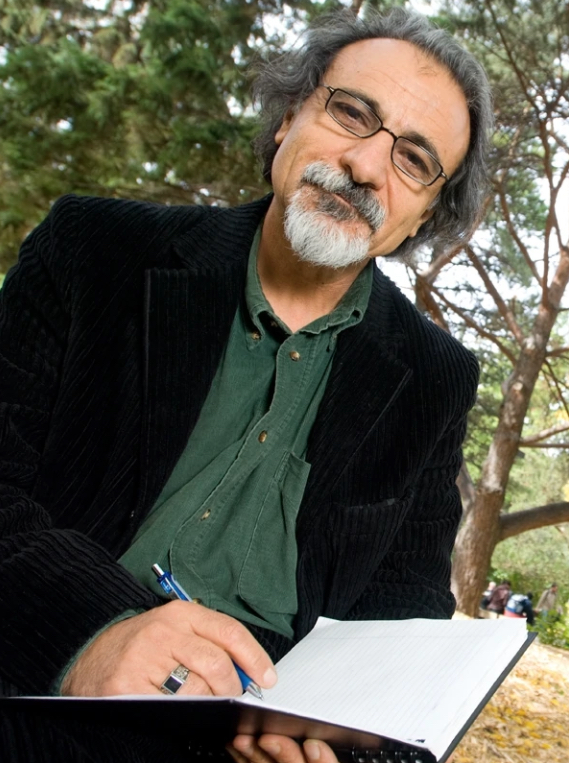

From 1986 to 1988, poet and journalist Jalal Barzanji lived in an Iraqi prison cell built for 15, holding 55.

He occupied a space 35 centimetres across. “That’s your home, your space for 24 hours, so we were sleeping on our sides. There was no space to sleep on your back,” says the Kurdish-Iraqi refuge who was imprisoned for being critical of the Baathist Party in his articles, and was Edmonton’s PEN-Writer-in-Exile in 2007.

In that hot, debilitating room, he wrote on scraps of paper snuck to him by one sympathetic guard. For two decades after his release, Barzanji ignored the poems and polemics he wrote in jail, but his recently published book, The Man in Blue Pyjamas (University of Alberta Press), translated from Kurdish, is a reflection on the writings.

Barazanji will be speaking at LitFest (CBC Centre Stage, Oct. 17).

What was it like to have a desk again?

It was the first time I wrote freely, ever, without fear of censorship. It changed my writing, my view and my style because I was writing whatever came to my thoughts. It was unbelievable for me, born in a country that doesn’t consider freedom of expression, and now I have freedom to write and space.

How did it change your style?

When you write under fear, you always hide something. You keep [constraint] on your mind. You try to use symbolism or masks to express yourself. But when you write freely, it’s different. [Censorship] affects even the concept and beauty of your writing because you use tools

to take you away from your heart and real feelings. Now, when I write, I consider it truly my real writings.

How has freedom of information changed Kurdistan and Iraqi-Kurdistan since the war began in 2003?

When I published my first book [of poems] , I submitted it and went through the censorship process; they rejected it three or four times. Now you can publish your book independently.

But on the other hand, there’s still no protection for writers. The consequences are the same [if you disgrace the government] . You can be arrested, you can be killed maybe.