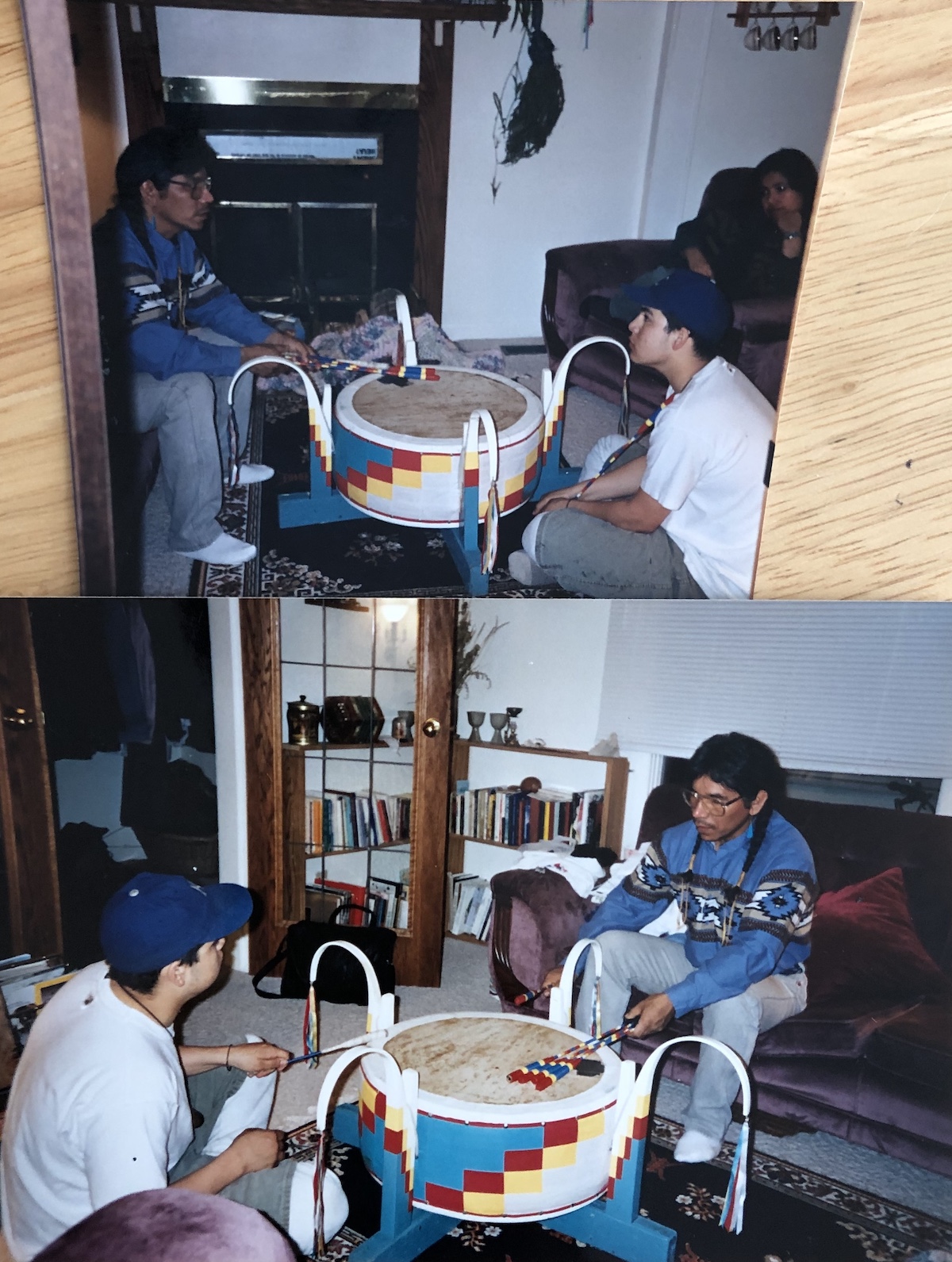

When Marek Tyler was 16, growing up in Saskatchewan, his uncle Glen, a renowned Cree fancy dancer, visited from Onion Lake Cree Nation, and brought a traditional powwow drum with him. Tyler, who had taught himself to play the drums on his family’s driveway, where the noise was tolerated, was instantly drawn to his uncle’s instrument. That week, Tyler’s uncle taught him how to play a round-dance beat, the heartbeat of the traditional Cree ceremony, where participants form a circle and move in a clockwise direction.

“Right then and there, it clicked for me,” recalls Tyler. “This felt unique and distinct, just for me. It was like meeting an old friend for the first time.” He continued to feel the same connection to cultural drums whenever he was near them, but he had few opportunities to learn. Soon, he was living in B.C. while touring North America and Europe with acclaimed indie rock bands like Kathryn Calder of The New Pornographers. But the beat of the family’s drum never left his memory.

It wasn’t until his late 30s that Tyler, who moved to Edmonton in 2015, began to imagine the role of the cultural drum in his own studio work. During a recording session for the alternative folk-rocker Kandle, he played a round-dance beat on a track and instantly felt as if he was honouring his uncle.

He began integrating Cree rhythms into contemporary indie rock and, in 2019, released an album with Kris Harper and Matthew Cardinal as nêhiyawak (pronounced neh-HEE-oh-wuk, meaning “Cree people”). Anchored by Tyler’s playing of carved cedar log drums, nipiy was shortlisted for the 2020 Polaris Music Prize and earned the group a Juno nomination.

For his next project, a solo electronic music album under the name ASKO (“to follow” in Cree), Tyler was inspired to document his Cree maternal family’s protocols for respectful cultural interaction. He spent three years honouring these protocols, starting with a days-long consultation with his mother, Dr. Linda Young, a residential school survivor, who also serves as his cultural advisor. Patience was key to his artistic process, as he consulted with other knowledge keepers, like his uncle Dale Awasis and University of Alberta professor Diana Steinhauer. Tyler carefully considered every musical decision, from sampling traditional drums to seeking permissions to work with sacred instruments. He followed his teachings by not bringing hand drums into venues that served alcohol. He collaborated with family and cultural experts, translating recordings of his great-great-grandfather into musical compositions that respected Indigenous knowledge transmission.

The self-titled album, released last year, is a living, breathing document in which modern electronic sounds become a vessel for ancient lessons. When performed live, there’s a visual component that’s equally important to the story Tyler is telling: video of Indigenous dancing is synced to the music, producing an immersive, multi-sensory audio-visual experience that bridges past, present and future. Reflecting on what it taught him, Tyler says, “If I work in a cultural way, if I exercise patience in learning, caring, and sharing, I take on the responsibility that affords me the opportunity to share without appropriating.”

Across North America, a cultural resurgence is reshaping the landscape of popular music, as Indigenous artists reclaim long-suppressed languages, traditions and stories. The movement, described by W magazine as a “pop cultural Native awakening,” is visible in everything from TV and film to fashion and literature. In music especially, the blending of ancestral knowledge with current genres has created a fresh, evolving sound. It reflects how Indigenous creators are reclaiming space and visibility in pop culture after generations of erasure and appropriation. It’s about reimagining Indigenous identity on modern stages, screens and in spaces that once excluded or misrepresented it.

Edmonton and Alberta have become a quiet powerhouse in the movement, home to artists blending cultural knowledge with boundary-pushing sounds. From Juno-winning family acts like Northern Cree to rising stars like Shawnee Kish, Celeigh Cardinal and Wyatt C. Louis, the province is rich with musicians turning personal histories into public declarations of identity and resistance.

Ella Coyes, who performs as Sister Ray (after The Velvet Underground song), grew up in Sturgeon County surrounded by Métis culture and music. The fiddle played a central role in Coyes’ earliest musical memories, with their father’s playing and jigging creating a foundation for their understanding of how music embodies cultural identity. The non-grid musical structure of Métis fiddle tunes, learned orally through community, gave them the freedom to experiment with song structures and phrasing.

“That’s where my interest in folk music began,” says Coyes, who moved to Toronto in 2020 to record their debut record Communion, released by Royal Mountain Records. “It felt like I knew it in another life, like it was in my DNA. People before me, who I’m from, were raised listening to this music and dancing this way. I think I’ve always had a hard time being in my body, and that music really put me firmly in my body for the first time.”

These experiences fostered a deep appreciation for the power of folk music to preserve moments and feelings across generations — something Coyes now channels through their own songwriting. Their music is a conversational brand of confessional indie rock that recalls the stream-of-consciousness lyrical style of Big Thief’s Adrianne Lenker, weaving together personal memories and introspective reflection.

Both their debut and sophomore albums, Communion and Believer, were longlisted for the Polaris Music Prize in 2022 and 2025, but Believer is a more confident and accomplished album. Recorded in a short span of time, it features an off-the-cuff, first-take-best-take quality that reflects the vulnerability Coyes displays in their songwriting, which is brighter and more uplifting than that found in their debut. Coyes prioritizes emotional authenticity over technical precision on Believer, creating organic and true-to-roots folk songs. And folk music, to Coyes, is a form of storytelling that connects them to the past. For their ancestors, music was a vital way to share knowledge and preserve memory, using only their voices and instruments to carry stories across generations.

“When we take contemporary stages in front of non-Indigenous audiences, we introduce people to the richness of our teachings, philosophy and culture,” says Alan Greyeyes, who chairs the Indigenous Music Office, which was formed in 2023 with the goal of supporting and developing Indigenous musicians. The new generation of Indigenous musicians, he says, have found a way to use contemporary music as a platform to showcase their identity, bridge traditional elements with modern expression and, in doing so, present their cultures as dynamic and multifaceted.

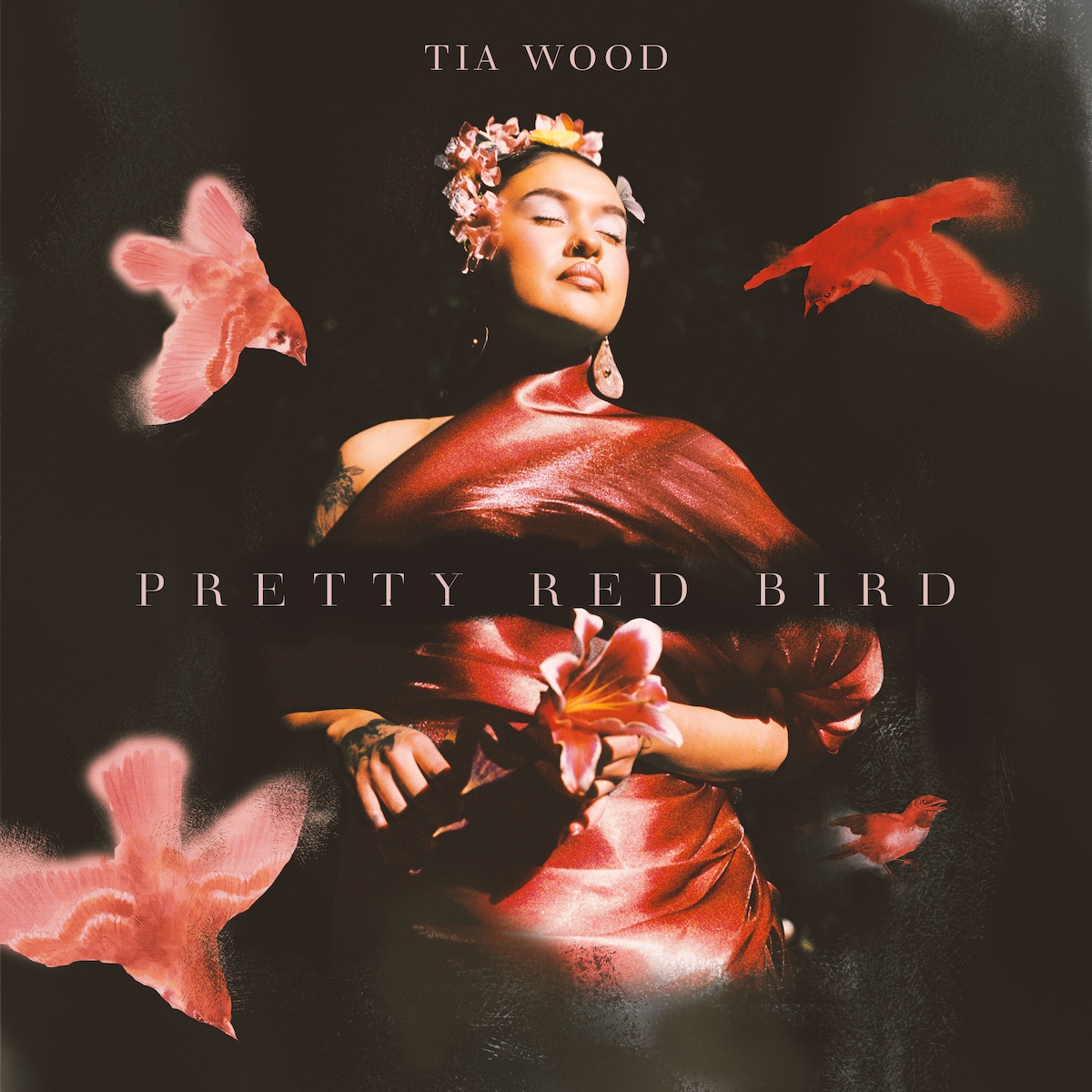

One of the most prominent voices to have emerged from this movement belongs to Plains Cree and Coast Salish singer-songwriter Tia Wood. Raised on the Saddle Lake Cree Nation reserve, a community of 6,000 people about two hours northeast of Edmonton, she comes from a musical dynasty. Wood’s mother, Cynthia Jim, played in the all-women drum group Fraser Valley. Her father, Earl Wood, is a co-founder of the legendary powwow drum group Northern Cree and a Juno Award winner — as is her sister, Fawn Wood.

That deep musical lineage informs not only her sound but the stories Wood tells. Her songs reflect the tension between where she comes from and the world she moves through, a balancing act between cultural pride and the pressure to conform. “Should I take out my braids or leave ’em in? They look at me like I’m a Martian,” she sings on her 2024 debut single “Dirt Roads,” a song about longing for home and the struggle of staying true to her Indigenous roots in a Western world that’s often hostile to them.

Wood first found her voice performing at ceremonies and powwows as a child, but she also grew up listening to artists from all genres, including Amy Winehouse, Dolly Parton and Avril Lavigne. In 2020, she began posting TikTok videos in which she layered Indigenous-style vocals over contemporary beats, which went viral, helping her amass over 2.2 million followers on the app and, more critically, gain the attention of major music label executives. She then decided to focus on a more contemporary sound once labels started reaching out with interest, feeling her family already had the traditional sound covered. For Wood, she relished the challenge of making modern pop music heavily indebted to the R&B she grew up listening to while still honouring her heritage.

Her debut EP, Pretty Red Bird, released by Sony Music last September, is a tight collection of spacious R&B jams. It showcases Wood’s rich and sultry vocals and a songwriting style that feels both uniquely hers and universal, referencing her Indigenous roots while also touching on topics that people who have never heard of Saddle Lake can still relate to, like on “Sky High,” an ode to overcoming obstacles in pursuit of your dreams.

What unites Tyler, Coyes and Wood is a commitment to making space for Indigenous identity in a world that has long tried to suppress it. Their work underlines the fact that reclamation isn’t static or nostalgic but forward-looking and deeply personal. And from basements at home to stages across the country, this new generation is not only preserving Indigenous culture but reshaping it, on their own terms, for generations to come. “When I close my eyes on stage now, I don’t see the audience anymore,” says Tyler. “I see my family.”

This article appears in the September 2025 issue of Edify