Josh Miller has seen the ups and downs of Edmonton’s film and TV industry from a front-row seat. Returning to his hometown in 1990 as director of script development for the original Super Channel, after a decade as a screenwriter in Los Angeles, Miller found the city enjoying a relative golden age in production. Director Anne Wheeler was here making distinctive Canadian features like Bye Bye Blues and Angel Square. Hollywood had chosen our burg as the location for a major TV movie, Small Sacrifices, starring original Charlie’s Angel Farrah Fawcett. There were even a couple of locally produced, one-hour Canadian drama series; Destiny Ridge and Jake and the Kid both had two-season runs for CanWest Global in Edmonton during the early to mid-’90s. Miller got into the action himself, after leaving Super Channel, when he became an executive of Minds Eye Entertainment and created the half-hour young-adult drama series Mentors, produced out of the former Allarcom Studio off 51st Avenue for Family Channel from 1996 to 2002.

“Television series in particular meant steady work and training, and they built infrastructure and skills here,” he says.

Then things dried up, thanks in large part to changes in Canadian content regulations and CRTC licencing practices. Sure, a handful of shows have been shot here in recent years – the low-budget sketch comedies Tiny Plastic Men and Caution, May Contain Nuts, the only season of the wholly forgettable NBC horror series, Fear Itself, and the edgy First Nations drama, Blackstone, for APTN. But the cold reality is that, faced with only intermittent work, much of Edmonton’s production community either left town or left the business over the past 15 years.

Cut to December 2017. That’s when Miller, two years into semi-retirement as a producer, and working on his own writing projects, was persuaded to rejoin the fight as CEO of the Edmonton Screen Industries Office. The ESIO was established by the City to replace the former Edmonton Film Commissioner’s office, vacant since 2015, following strong lobbying from producers, guilds, unions and other stakeholders representing Edmonton’s various screen storytellers.

Cracking open the limited mandate of his predecessors (largely focused on luring out of town, or so-called service, productions here), Miller views his job as helping a diversified and nimble local screen industry co-exist and grow alongside Calgary’s more conventional film/TV industry. He doesn’t see Edmonton competing head to head with our neighbour to the south for major movies and big-budget series. Calgary (home to shows like CBC’s Heartland and FX’s Fargo) has the advantage of a large new production studio, nearby foothills and mountains, and more direct airline service to the United States going for it. Miller instead envisions Edmonton as a location for lower budget features and TV series seeking distinctive geography like our river valley. “We need to start by rebuilding our crew base here,” he says. Miller is after more than just film and TV business though. He points to the city’s growing contingent of interactive digital media developers, led by industry heavyweight, BioWare, as another area of local strength to build upon. But, most of all, he wants to support Edmonton’s screen-based storytellers (whether they are producing narrative for film and TV, web series, or interactive digital media like games and mobile apps) to own, develop and market Edmonton-based intellectual property. He views such homegrown creative capital as part of the city’s path to economic diversification.

“When I think about screen media and the potential out there, I use this analogy of walking into an airport lounge and seeing how many different screens are being used at any one time,” he says. (Miller counts 10 but challenges us to list them for ourselves, beginning with phones and big-screen TVs.) “All those people and age groups -what’s the value of all that content on those screens? If we focus on that, and especially on the possibility of local ownership in its creation, it could be a great opportunity for Edmonton.”

Like Miller years before her, Chantell Ghosh, executive director of the Citadel Theatre, has come home from a lengthy stint in the United States. Raised in St. Albert and educated at the University of Alberta, Ghosh practised law in Edmonton before following her husband’s career to stops in Pennsylvania and Florida. In addition to raising five kids, she worked in communications and public relations for Direct Energy’s HQ in Pittsburgh, then moved on to head up marketing for the Pittsburgh Ballet. When her husband was transferred to Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Ghosh took a job in marketing and communications for Spirit Airlines. Her return to Edmonton came about following a casual conversation with City Councillor Scott McKeen at the Edmonton Film Festival during a trip home to see her parents a couple of years ago. McKeen asked Ghosh if she’d ever come back to stay. She responded absolutely. Months later, conversation forgotten, Ghosh was surprised by a call from a corporate recruiter asking if she’d be interested in the vacant position of Citadel ED.

“It feels a bit like the mothership calling me home,” she says. Ghosh’s first experience with the Citadel came when she was nine years old, riding in from St. Albert to see W.O. Mitchell’s The Kite with her class from school. “We all trundled out of the yellow bus. I remember watching this amazing show and taking my little bag lunch and eating in the atrium under that waterfall. I loved this building.”

Ghosh has been on the job since the start of the year. (“From Florida to Edmonton in January – nobody should ever doubt my conviction.”) One of her first acts as executive director was a radical one: She ended the Citadel’s longstanding prohibition on taking drinks from the bar into the theatre. It was an instant hit. “I’m not sure what that says about me,” she quips, “but patron experience is high on my list of priorities. I don’t want anybody having to chug a glass of wine so they don’t miss the cut-off for intermission.”

In broader terms, her role is to support the creative vision of Artistic Director Daryl Cloran with marketing strategies that will help fill the theatre and ensure it’s a sustainable hub to the creative industries in Edmonton. Just as Cloran has set out to do with bold and varied programming in his first two seasons, Ghosh wants to expand the Citadel’s tent. “Like every arts organization in the traditional sense – the symphony, ballet, theatre – we struggle because ours is an older demographic as a rule. So how do you reach down and engage that next generation of theatre goers as patrons, as supporters?” she says.

Ghosh’s approach includes a shift away from reliance on glossy mailers to greater digital marketing. “More people are on their phones and computers nowadays versus answering their land lines, if they still have one, or going to their super-box once a week.”

She also sees the value of collaborating instead of competing with other arts groups around the city. “I’m a strong believer in a rising tide lifting all boats,” she says. “I had the good fortune of working in a Cultural Trust model in Pittsburgh. We (the different arts companies) realized that when we worked to information-share, while respecting everybody’s data base and the privacy of their clients, it allowed us to cross-market to one another and we found it didn’t take away from anything, that everybody got more engagement and people would see more things.”

And Ghosh is bullish on what there is to see here. “I love how everybody has upped their game. I moved away and always thought that we had great art here – great music, great opera. But living elsewhere and seeing different groups and coming back, I am confident that we have world-class organizations here that I would pit against some of the leading arts organizations in North America.” Byron Martin believes we can’t have too many laughs in a city like Edmonton. Last spring, the founder and artistic director of Grindstone Theatre invited a bunch of witty friends and acquaintances to join him in a renovated storefront a few blocks south of his troupe’s previous home.

“Our mandate is to create opportunities for emerging artists, so it was always on my radar to find out what we could do to help other companies,” he says. “I noticed we weren’t the only ones doing shows in a church basement because there was no other space.”

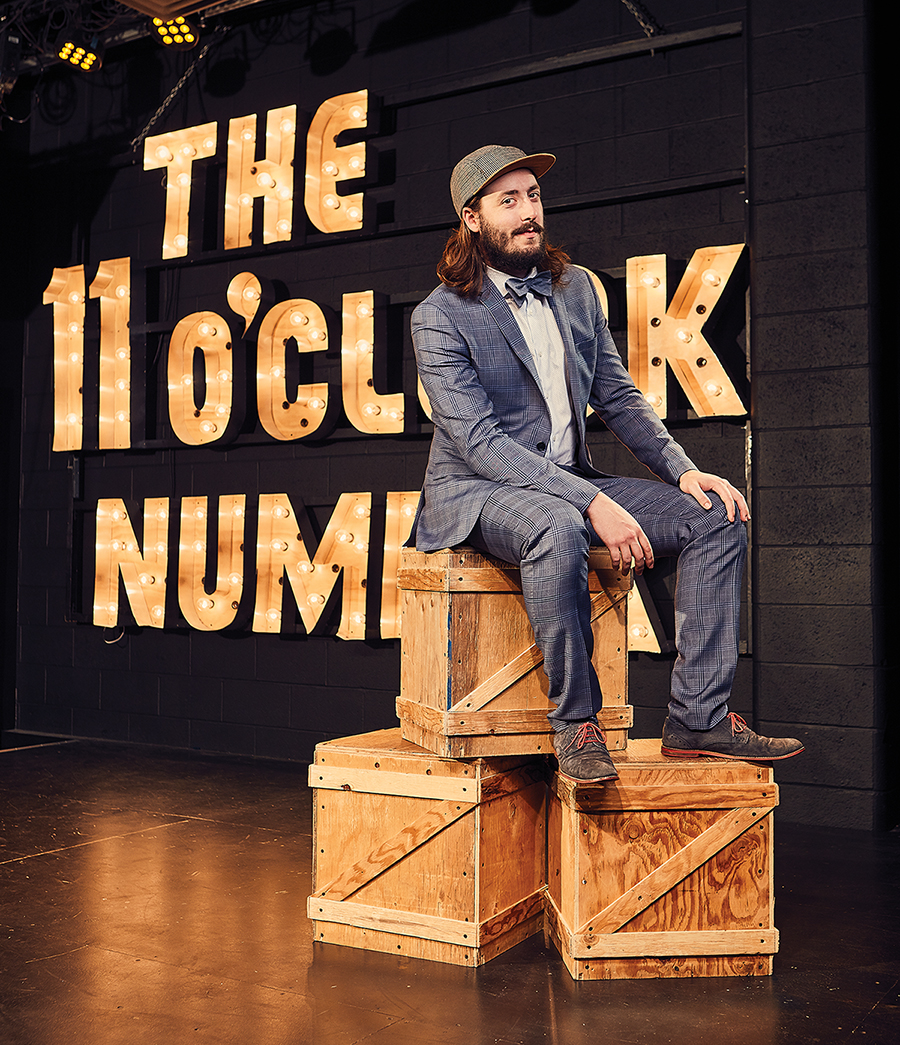

Since opening its doors in April, The Grindstone has served up a wildly varied menu of comedy six nights a week. A glance at the monthly calendar reveals improv (on bent and twisted themes ranging from Shakespeare to Star Wars), sketch, stand-up, burlesque and spoofy late-night talk shows. In all, more than 30 different companies produce 14 shows a week in the space. Regulars include well-known local performers like Donovan Workun, Neil Grahn and Dana Anderson. Martin’s own flagship, the long-running improvised musical comedy The 11 O’Clock Number!, runs every Friday night.

It’s an ambitious undertaking. After all, even a venue like Yuk Yuk’s, bolstered by national brand recognition and the steady foot traffic on West Edmonton Mall’s Bourbon Street, only dares roll out the funny stuff three nights a week.

Truth told, it’s partly a product of necessity. “I knew the only way to do a building would be to get other people involved, because we wouldn’t be able to carry it ourselves,” Martin admits. Acting as combination landlord and curator, he rents out The Grindstone to selected guest companies for a modest nightly fee plus a $2 surcharge per ticket sold. “We could charge way more than we do, but the goal is to make it super affordable. Even if there are only 20 people out at a show, they’re still surviving,” Martin says.

The Grindstone features a cozy 90-seat performance space fronted by a cafe bar. The menu in the latter offers comfort food like beer cheese chowder and bite-sized grilled cheese sandwiches with tomato bisque, washed down with a good selection of Alberta craft beers and special Grindstone cocktails.

The Grindstone might be a few blocks east of the main nightlife pulse on Whyte Avenue, and that’s risky, but Martin is confident the concept can survive beyond the novelty phase. He likens the club to a year-round Fringe Festival of comedy. “I’m excited about the community that’s going to develop naturally from having the bar in front of a cross-over of different audiences, and for people to get exposed to shows they’ve never seen before. And I’m excited for the artists to start talking and collaborating, hanging out in the bar together and saying we should do this show.”

This article appears in the October 2018 issue of Avenue Edmonton