Edify is publishing this series as a tribute to life of singer and lyricist Ken “Chi Pig” Chinn, who passed away this summer. Part One. Part Two.

PART 3: FIRST ALBUM

Think of the most important bands in the history of punk rock; of course there’s the holy triumvirate of punk—the Sex Pistols, the Clash and the Ramones—but you’d also think of the Damned, the Buzzcocks, Black Flag and, of course, San Francisco’s Dead Kennedys.

Led by the socially-active Jello Biafra (who once ran for mayor of San Francisco), the DK were the leaders of a movement that shifted the headquarters of the hardcore movement from New York to California. So, when DK decided to tour Western Canada in 1984, it was sure to be one of the major events on the prairies’ burgeoning punk scene.

And who did Biafra hand-pick to be the opening act on the tour of the prairies? None other than SNFU, those Edmonton punks who were preparing to record their first album for the B.Y.O. record label.

The gig went off at the Sportsworld Roller Disco — and Biafra was so impressed with the young Edmonton punks, he asked SNFU to continue as the opening act for the rest of the Canadian tour, which included stops in Regina, Saskatoon and Winnipeg. Later, the band would be offered an opening slot for the next Dead Kennedys’ tour of the United States, but mechanical problems thwarted those plans. The engine fell out of SNFU’s touring van, forcing them to pull out of the American DK tour.

The breakdown occurred in Idaho; and the band was forced to abandon ship and bus back home to Edmonton, a 36-hour ride north. Worse yet, the band didn’t have clean clothes, and the members dealt with scabies for the bus trip; tearing away at itching skin while confined in the bus.

But, touring with the Dead Kennedys was the preparation SNFU needed; the band was about to go to Los Angeles to record their first record for the Stern brothers, owners of the B.Y.O label. Just a few weeks before Christmas, guitarists Marc and Brent Belke, Chi Pig, bass player Jimmy “Roid” Schmitz and drummer Evan C. Jones got in the van to begin their California journey.

But the band didn’t quite prepare properly for their trip. The guys were still so young, and maybe more than a bit naïve. No one thought that a work permit was a necessary item to have in hand when trying to cross into the United States.

When the band got to the Alberta/Montana border, they were told to turn back; the customs officials made sure to do full checks on the fivesome when they saw these freakishly dressed punk rockers claiming they had work across the border. Marc was nailed on parking tickets, and was forced to pay them at a nearby location. But Schmitz was truly sunk — he had a prior conviction for simple drug possession. But, when it came to crossing the American border, he may as well have killed a guy.

The band was told to hightail it; and they did. Hastily, they thought up a plan B — make the 10-hour drive west to Vancouver, and try to sneak Schmitz across into Washington State. The band had a friend there by the name of Bob Montgomery, who was the road manager for Vancouver punk act, DOA. The feeling was Schmitz would have a better chance getting across with Montgomery. They would rendezvous with the rest of SNFU on the other side of the border.

Schmitz and his accomplice were successful; it was a Sunday, and British Columbia laws at the time forbade the sale of liquor on the Lord’s Day. When Montgomery and Jimmy got to the border crossing at Blaine, Wash., the discussion with the customs officials were short and to the point.

Said Jimmy: “He asked us where we were going and Bob answered, ‘Blaine.’ He asked us why we were going, and Bob answered, ‘Beer.’ He just waved us across, without even looking at our IDs.”

But the rest of the band was nailed for not having work visas. The thought of needing work permits in order to professionally record an album in the United States hadn’t crossed their minds. The guy with the drug record had got across the border, but the rest of the band were blocked. Desperate, they moved to another border crossing — and made it. Now, they had to find Schmitz. He had been dropped off at the first Denny’s across the border. Frustrated by the wait, and the fact it was getting dark, he decided to book a room at the motel across the street from the eatery. Eventually, the rest of the band tracked him to the motel. When they knocked on his door, they found Schmitz, simply wrapped in a towel. He was getting ready to crash for the night, simply because he figured his bandmates weren’t going to make it across.

But make it they did, and the album was recorded at Track Record Studio in Los Angeles, where the Beach Boys had recorded so many of their hits.

When time came to mix the record, SNFU found that the recording sessions had gone overtime — and all they had left was 12 hours. The band was forced to mix 10 songs in just half a day. But, the short mixing sessions may have been a blessing — it gave the debut record, … And No One Else Wanted to Play, an edge.

And the accompanying tour of the American southwest was a mixed bag; Schmitz recalled that the Phoenix show was a surreal experience. It was a big gig, with 400-500 punk kids crammed into the back room of a church (that’s right, a church).

“And the promoter got up on the stage and started going on about all the violence that was going on in this club, or church,” said Schmitz. “And then the people started to circle dance, something which hadn’t come to Canada yet. And I remember that when we would stop playing in between songs, they just kept on dancing.”

The Tucson show, the next on the mini-tour, was more sedate, but the SNFU boys made a scene at a local post-show house party with a patriotic but musically-abysmal stab at “O Canada,” which came as a shock to most of the punks there.

San Diego was a traumatic experience for the band. When lost people think of San Diego, they think of Los Angeles’s quiet, civilized and conservative neighbours to the south. A city dominated by Navy brats and tourists looking for Sea World. But for SNFU, San Diego proved to be even more whitebread than expected.

“A lot of those Navy guys are skinheads,” remembered Chi. “And it made San Diego a rather dangerous place to be.”

Orange County, which has always been the West’s headquarters of punk, was an inspirational show for the band, just for the fact the people at the gig actually sung along to “Victims of the Womanizer,” a song that had been recorded for a meaning that the song had earned a following in Southern California, even though SNFU had yet to release a full-length album.

The band waited on pins and needles for the album to come out — finally, in the spring of ‘85, their dream was realized. The change in attitude on the home front was almost instantaneous — club owners who once ignored the band were now offering SNFU shows.

“We didn’t see the record until six months after we had recorded it in L.A.,“remembered Chi. “When it came out, things changed for us really quickly. People took the band more seriously. Before, we were a group of drunken crazy people. Then, those same people give you a lot of respect the second the record comes out. At the time, I had no idea we’d be doing many more records over the years. I’m still amazed that people would still voluntarily spend their money on our music.”

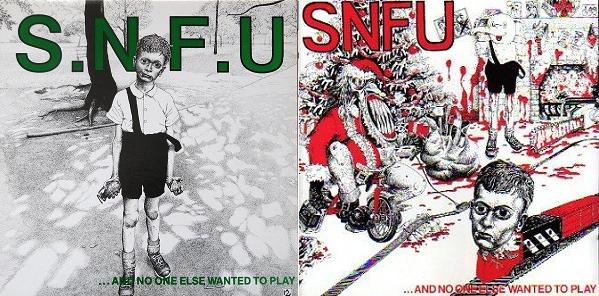

The album, …And No One Else Wanted to Play, didn’t go gently into that goodnight. It came out with four different album covers, showing that SNFU already had some marketing savvy. It was the first full-length forum for Chi’s cheeky lyrics, written while on bathroom breaks during his day job at Saveco.

“I remember that Keith Sharp from Music Express didn’t like the album,” says Chi. “He said our album was ‘…crude, full of toilet humour.’ I laughed when I read that. I thought, hey, that’s funny because most of those songs were written on the toilet.”

The only exceptions was the track “I’m Real Scared”— the lyrics were actually penned by Mike McDonald of Jr. Gone Wild fame; SNFU borrowed the words and put them to a special thank you to Ma Jones, Evan’s mom, who had provided the band with their rehearsal garage.

Unlike so many of their punk contemporaries, SNFU was able to retain their sense of humour; that was evident on …And No One Else Wanted To Play. SNFU’s strength has always been the fact that its members have never taken themselves too seriously; that attitude came to the fore on …And No One Else Wanted To Play’s punk anthem, “Cannibal Cafe.”

Chi came up with the idea while munching on the offerings at a long-gone Edmonton eatery.

“It was the worst burger I ever had,” laughed Chi. “I wondered if they were serving dog meat to me. Then the thought crossed my mind; am I eating people?”

WHAT STRUCK ME about the reaction to Chi’s death was, well, how widespread it was. The hashtag #ripChiPig trended on Twitter. For someone who never wrote top-10 hits, whose versions of SNFU didn’t hit the mainstream, he was well-remembered. (With all the member changes, breakups and reformations over the years, “versions” of SNFU is the correct way to describe things.) His memory was feted bankers and city councillors, by suburban parents and musicians you wouldn’t consider punks in the least.

That’s the thing. Most of us who listened to punk music in 1970s and 1980s and into the 1990s… grew up. Some might still have the tattoos, but the earrings are gone. Our bikes that had anarchy stickers on them have been replaced by SUVs. We pay mortgages on the suburban houses the 20somethings versions of ourselves swore we’d never own.

But Chi Pig remained rooted in time. He never stopped being the character that he invented. He was always the showman. Like Bowie, and I don’t think that’s a stretch, the persona was constant, whether it was 1985 or 1995 or just a few months ago. He was 57 when he passed; but icons don’t get old, do they? As the kids who grew up listening to SNFU got married and had kids, he remained a twentysomething icon, in our minds.

It also makes us nostalgic. We think back to those shows we saw when we were younger. We think, mistakenly, that our kids will never see bands as cool as the ones we saw. And the memories of those show grow.

When I was researching this project years ago, one show was brought up over and over. The final show SNFU played at the Spartan Men’s Club, a short-lived venue in the city’s northeast. This all-ages show took place in 1985, right about the time the band released… And No One Else Wanted to Play.

The fire code stated that at the most, 164 people could be shoehorned into the club. But on that night in ‘85, over 500 punk-rock fans jammed the place. The doors and fire exits were thrown open to accommodate the overflow crowd. Since playing their first Spartan gig as a band in 1982, the members of SNFU had been a regular part of the city’s thriving all-ages punk scene. SNFU’s manager, “Gubby” (Gabor Szvoboda), was booking Canadian punk acts at Spartan for the last three years, from the Subhumans to DOA, Jerry Jerry and the Sons of Rhythm to Jr. Gone Wild.

“There were the gigs that I put on for SNFU where I didn’t make a dime,” recalled Gubby. “Not even when they were drawing 500 to 800 kids in Edmonton. Any money made went into SNFU. And after those shows, everyone would leave the gig and me and a group of amazing friends would stay behind to clean up the club. SNFU was a group effort in the early days and that ‘group’ needs to be remembered too. Those people didn’t do it for any other reason than to be a part of the ‘scene.’ And it was a great scene too. SNFU was the band that rose out of that ‘scene’ to take their message and show throughout the world. But it was a collective effort for sure.”

The cops came to down to check out what all the racket is about; they warned Creighton Hoopalo, a teenager — and Gubby’s assistant — who was working the door this night, that the show would be allowed to go on if all the alcohol on the unlicensed premises ws gone within a half-hour. The club was cleared; thel patrons were forced to ditch or guzzle their liquor stashes. The club was then repacked; and the cops arrived 30 minutes later to find a dry establishment.

How crazy was the scene? Hoopalo, who passed away in 2015 — the ticket-taker from the famed oversold night — was a prime example; as a teenage fan, he was well-known to the members of SNFU; at one fateful Spartan show, he shattered his ankle in the pit. But, with leg still encased in cast, he staggered to the next SNFU show.