Walk into the Citadel Theatre’s Lee Pavilion, and you’ll find it. Its metal pins and shattered disc rise out of the greenery like spaceship wreckage on a jungle planet.

Its name is “Genesis.” And it’s one of sculptor Roy Leadbeater’s most famous pieces. A disc of metal is molded to look pockmarked, like the surface of the moon or a meteorite. The disc is then shattered into two bits; the cut isn’t clean. It’s a violent, jagged break.

Originally, Leadbeater was toying with the idea of a lunar-looking sculpture in the early ’60s, when man first began to leave the atmosphere to explore space, and he was a Calgary-based sculptor looking for his work to be seen. The moon was visible – but we hadn’t visited it yet. So Leadbeater made a sculpture based on how he thought the moon would look, close up.

But, there was one problem. Before he could wrap up the project, man had visited the moon. The myth of the moon had given way to science. And what good was a sculpture of what the moon might look like if Neil Armstrong had already taken one small step for man on its cratered surface?

Then, he read a book on Einstein – and it gave him his eureka moment. He was fascinated by science, and found the idea of the Big Bang so riveting, he reframed his lunar disc by shattering it to look like it was being ripped apart. It became an artistic re-creation of the explosion that created the universe.

The idea for “Genesis” was born in the years that man was going to the moon. And, in 1984, a decade and a half later, it finally came into public view, taking its place at the Citadel Theatre.

It took decades for the sculpture to evolve. The fact that Leadbeater was able to transform his work shouldn’t be a surprise. That’s because Roy Leadbeater is a man of transformations. He was abandoned by his parents when he was a child; he travelled the world’s oceans as a member of the Merchant Marine; as a member of the British police, he tried to keep the peace in post-Second World War Palestine.

And then there’s the Roy Leadbeater who is known to Canadians. The famous sculptor, the man behind some of the most noteworthy monuments you’ll find in this country.

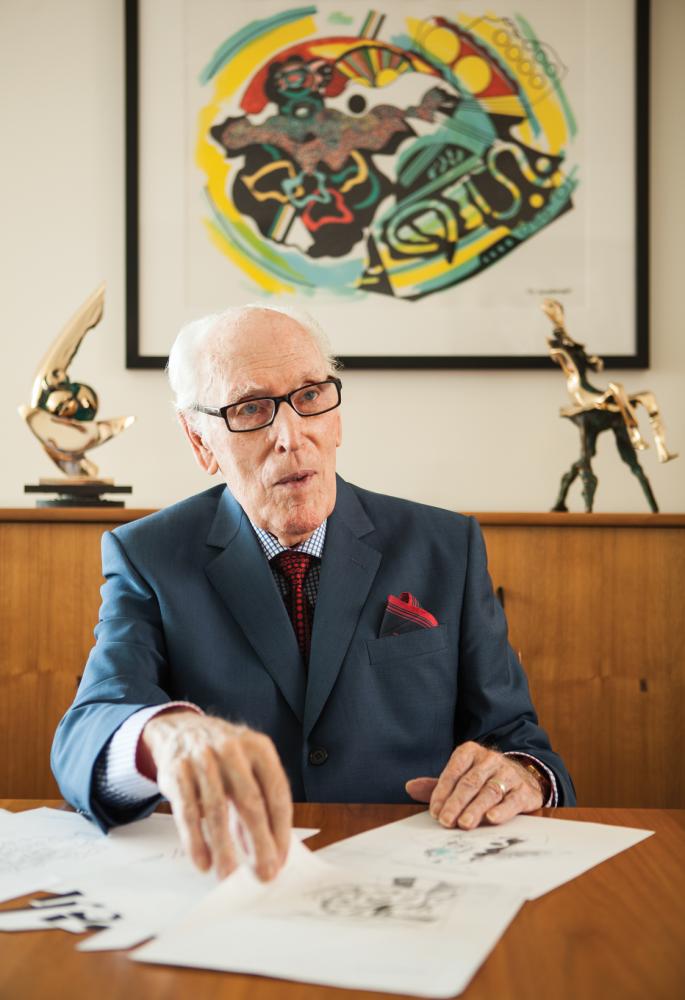

Now 86 years of age, Leadbeater lives with his third wife in a condo that overlooks Edmonton’s river valley. It’s white and clean, like a gallery. The backdrop serves to showcase his work, from sketches of geometric shapes to tables that look like Industrial Revolution machines turned inside out.

It’s a world away from a London orphanage, which is where Leadbeater spent much of his childhood after being abandoned by his parents.

Leadbeater was born in Ashbourne, England, into the class system; his parents were servants, and they told him that, while they weren’t “of the house,” they could still enjoy some of life’s luxuries. They saw the food before it went out to the lords and their ladies. And while they didn’t have the privileges of blue blood, by being in the house so much of the time, they could at least see how 1930s English aristocracy lived from the best seats in the house. It was the stuff of an Evelyn Waugh novel.

Leadbeater was just eight years of age when his parents told him they were going to go off to the store and they’d soon return to the flat. Leadbeater and his younger brother, Paul, who was just six at the time, waited for them to come back. Hours turned into days. Days turned into weeks.

Their parents weren’t coming back. The two Leadbeater brothers moved into an orphanage.

Roy discovered that he loved art – especially sketching -and, when he was ready to leave the orphanage on his 14th birthday, he asked if he could go to art school. But he was told it was important for a young man with no one to depend on but himself to have a trade.

“They got me a job as an apprentice electrician at a hospital,” he recalls. “There were so many wounded there for treatment, men coming back from D-Day. And one of them asked me ‘How come you’re not in the army?’ I was too young to join, but I could help by taking a job in the Merchant Marine.”

Desperate to help in the war effort, Leadbeater left England behind and found himself in the engineering room of a Merchant Marine ship. But, the life of a sailor didn’t completely diminish the emerging artist within; on the chalkboard where the crew’s duties were posted, Leadbeater would regularly leave a doodle or two behind.

Leadbeater was part of a crew transporting equipment for an airstrip and he sailed through some of the roughest waters in the world – the southern Indian Ocean.

But, the teenage sailor found that he loved the sea. Even when the waves made his crewmates barf up their breakfasts, he found something relaxing about being a speck in the big blue. “You hear every creak and moan and groan in the engine room,” says Leadbeater. “And when you get into rough seas, you’d feel the strain in two diesel engines, each 16,000 horsepower. You didn’t ride on top of the waves as much as you crashed through them.”

The love of the sea didn’t mean the voyage was without tension. When Leadbeater left home for the first time, the world was still at war. The ship was headed to the Pacific theatre, where it was to supply troops. There were whispers aboard the ship that the Japanese had perfected a sub that could be dropped into the ocean well away from the fleet, meaning the merchant ships could be fat, easy targets for the rumoured new enemy weapons.

And Leadbeater didn’t know how to swim. Surprisingly, not knowing how to swim was a common trait with sailors.

“If you were torpedoed, you knew you were never going to swim to shore,” says Leadbeater. “You’d never make it. The other sailors told me the best thing was to take a good gulp of water and go down with it.”

But, when they got to the Panama Canal, news spread that the Americans had dropped the bomb on Hiroshima. The crew knew it was the beginning of the end.

Leadbeater’s voyage would take him to India, the Philippines and to Singapore. He remembers Japanese prisoners of war unloading the boat and seeing the lights of New York City when the ship got close to the American shore.

But, after his tour was done, he found himself back in post-war England. Still a teen with nothing to do, he wanted another adventure.

He wouldn’t have to wait long. While the Second World War had ended, the world was not a peaceful place, as Leadbeater would soon find out.

After Leadbeater returned to England, his wanderlust was interrupted by a strange message received from an even stranger messenger. A girl who claimed to be his sister asked him to meet her in a train station in Birmingham, England’s second-largest city.

The girl informed Leadbeater that she’d be waving a yellow handkerchief on the station platform.

Intrigued, Leadbeater answered the invitation. He spotted the girl with the yellow handkerchief. She told him that there was someone who wanted to see him.

“She tells me she is with someone that she knows I will want to meet, and she takes me right to my mother,” recalls Leadbeater. But, at this point in the interview, the tone of his voice isn’t warm. “Then, my mother puts her arms around me, but I couldn’t stand it. I could never forgive her. I could never forget what she’d done to me and my brother. That we’d be left with some food in a room in a flat in London.”

The reunion was brief. There would be no reconciliation. Leadbeater couldn’t forgive what his mother had done to him and his brother.

Leadbeater wonders out loud if there is something more that could have been done, whether he should have been so quick to reject his mother. It’s clear he’s still trying to understand why his mother left him behind 78 years ago. Later, he admits that he enjoys watching episodes of Downton Abbey; to him, the show rings true. On the show, when the wealthy family begins to lose its money, the servants are the first to go. Leadbeater wonders if that’s what happened to his parents – that they’d found out they no longer had a blue-blooded house to attend to, and didn’t know what to do with a young family to support.

Leadbeater’s time in England didn’t last very long. Even though the Merchant Marine had given him life experiences well beyond his 18 years of age, he wanted to leave again. That’s when he spotted a notice which spurred him to enlist with the British forces, who were trying to keep the peace between Jews and Arabs in Palestine.

“When I got back to England, I was still too young to be called up to the army, navy or the air force,” he says. “Merchant Marine was a civilian job. Then, I saw a large poster of a mounted policeman in full regalia chasing a pig. I thought that I’d always wanted to ride a horse. My father was apparently a good horseman. And, you know, the son always want to beat the old man.”

Leadbeater arrived in Palestine on Christmas Day, 1946 – half a year after the Irgun, the Israeli nationalist group, bombed Jerusalem’s King David Hotel, a station for British forces. Ninety-one people were killed.

The young Leadbeater realized there would be no romance. In the land that would become Israel, the British police force was a target for extremists on both sides. The Palestinians and the Jewish sides could only agree on one thing: That neither wanted the Brits involved in their fight.

“Jersualem wasn’t the city I sang about in choir,” says Leadbeater. “It was a city of murder and mayhem. If I had a wish, it would be to get the Palestinians, Arabs and Jews together so they could figure out how they could all live together. I tell you, after getting to know them, they are some of the sharpest people I’ve ever met. If they could get together, they would be a force to be reckoned with.”

In the months that followed, Leadbeater struggled with the conflict. He met wonderful people on both sides – but he understood that there was always a target on his back. He was stationed in Jericho, working with Bedouins who looked to cut off smugglers and arms merchants flowing into Palestine from other areas of the Middle East.

He remembers that, after more than 100 Arabs were killed in the massacre at Deir Yassin, the British were perceived to have allowed it to happen.

British convoys were attacked by both the Arabs and Israeli nationalists.

“Our dilemma, being British, was that we were sympathetic to what had happened to the Jews in Germany. But now, there were Jewish individuals who were trying to kill us. We were being shot at by the same people we had sympathy for.”

Those sympathies remained with Leadbeater throughout his life. He sculpted a menorah that was given to Shimon Peres, the former president of Israel. In 1986, he completed “Ashes to Life,” a Holocaust memorial placed in front of Calgary’s Jewish Community Centre. Three figures, with flowing bodies and cubed heads, rise from the flames.

Fast forward to 1953; Leadbeater has suffered through the death of his younger brother – who was killed in a car accident. With no hope of reconciliation with his mother or her new family, Leadbeater’s only real family was his wife, Mabel. On the recommendation of a shipmate, they decided to move to Canada and settled in Edmonton. With limited education, but lots of military experience, Leadbeater was well-suited to physical work in harsh environments.

Newly arrived in the Alberta capital, Leadbeater queued up at the employment line. He was told that he could get a job right away if he was willing to get on a plane for Uranium City, Sask. – a remote town with a reputation for being home to roughhousing gamblers and drinkers. It was a place where the men, flush with cash, were rumoured to play just as hard as they worked. It was Fort McMurray before there was a Fort McMurray.

Thinking he needed to look good to impress the bosses, Leadbeater wore a fine suit on the plane ride northeast.

When he got there, he knew he was overdressed. “The foreman looked at me and said: ‘I hate Englishmen, but I hate bohunks and DPs even more,'” recalls Leadbeater.

But that rough beginning wasn’t indicative of Leadbeater’s experience in the mines of Uranium City. He remembers the food rations being massive – that every man could eat like a king.

“And what I found is that the miners read the most interesting books, had the most interesting minds. They were diamond drillers who had travelled the world.”

Leadbeater worked during the day, filling the lanterns for the miners and helping start up the oxygen compressors. He would doodle at night, inspired by the mighty machines that were part of the mining operation. Uranium City was in the wilderness, and Leadbeater would often take a canoe and row past what he imagined was the undiscovered country. He would imagine he was the first man to ever travel these wild spaces.

Because of the connections he made in Uranium City, Leadbeater lined up a job in Calgary, where he and Mabel could reunite. And it was there that he could reconnect with his art hobby. He spent time at the Calgary Allied Art Centre, working with clay. His work was informed by his love of the sea, geology and science. Rocky surfaces emerged. Waves appeared in his work.

The turning point came when Leadbeater, despite a lack of certified art education, entered a national gallery competition, and won. He never had a diploma – and yet he was building a reputation, all the while keeping his day job.

And that was the thing; Leadbeater didn’t think he’d ever be able to make art his full-time job. He was working at Shell, but word was getting out that he was an up-and-coming sculptor. An offer came to him from an official at Dominion Bridge who had seen his work. The proposal was made even sweeter with the provision of steel – otherwise unaffordable to Leadbeater – for him to work with. Dominion Bridge allowed him to come to the factory after hours, to give him space for a workshop. Leadbeater now had a place to work and better material to use.

By the 1970s, Leadbeater became a hot commodity – in Edmonton, his new home city. He and his second wife, Betty, were early into a 30-year marriage that would last until she passed away. Leadbeater not only enjoyed regular gallery showings, but was a sculptor of choice for Alberta’s rich and powerful.

In fact, he met Betty through a commission. Her previous husband, Bill Buchanan, was a powerful Edmonton lawyer, who had decided to give his wife a unique gift. He commissioned Leadbeater to create a sculpture for her. But, as Leadbeater worked, Buchanan died during an open-heart surgery. Now widowed, Betty fell in love with Leadbeater – and they married.

Before leaving Calgary, Leadbeater’s work was backed by the family of famed Calgary tycoon and philanthropist Alvin Libin, who acted as his benefactors. And, in 1967, he created what was his first landmark, internationally renowned work. He won the right to create the sculpture for the Four Western Provinces Pavilion at Expo ’67 in Montreal. The 28-foot “Kinetic Sculpture” had moving parts.

Leadbeater’s description of his landmark work is succinct. “It was a 28-foot machine gone mad.”

With Leadbeater holding a national profile, having one of his sculptures in your hotel, head office or home became a major status symbol. In fact, Leadbeater remembers getting a commission from Pat Bowlen, the famed American-born tycoon who has since moved back to the United States from Edmonton – and now owns the Denver Broncos of the NFL. Bowlen’s father, Paul, was a giant of the Edmonton oil industry, as the co-founder of Regent Drilling, one of the companies that launched the Alberta boom.

Paul was famous for not mincing words. And when he found out that his son had hired Leadbeater to do an abstract work for the family’s personal collection, Paul was sure that the sculptor was an artist, all right. A con artist, that is.

“He told me that he thought I was taking them for a ride,” Leadbeater smiles. Then he whispers, as if sharing a favourite secret. “One day, he walks up to me, looks at me, and asks, ‘what the f— is this sculpture business?'”

But, throughout the 1970s and 1980s, when Leadbeater became one of Canada’s leading sculptors, he never gave up his day job at EPCOR, which helped subsidize his artistic endeavours. At the height of Leadbeater’s popularity, he and Betty ran a foundry that had 11 employees. And, once the employees were paid, the Leadbeaters found there was little money left over.

To get public commissions, artists not only had to have original visions, but the ability to keep costs affordable for a community or charity. So, despite the contracts, the Leadbeaters walked the financial tightrope.

And the art business tends to be feast or famine. Even when Leadbeater had a good year, he understood that he might not sell another piece. That’s true, even in 2014.

“Last year, I sold every piece I had to Gerry Levasseur [who owns Maligne Lake properties] . This year, I’ve sold just one sculpture.”

Roy Leadbeater has led me here.

I’ve made the short five-minute drive that takes me from Morinville to Cardiff Echoes, a subdivision in Sturgeon County where houses ring around a central park.

I park the car on the corner Mill Road and Discovery Drive, and walk on a crumbling pathway that leads to a park. A black Lab, on an uncomfortably long leash, comes to the edge of a resident’s property line, teeth bared. It’s growling just a couple of feet away from me, guarding the park like Cerberus.

I move past the dog and walk across a yellowed soccer field that cries out to be watered. At the other end of the park, I find what I am looking for, ringed by a half circle of evergreen trees. Red-winged blackbirds squawk in the meadow.

It’s Leadbeater’s “A Celebration of Life – Children Having Fun.” It was erected in 1996 as memorial to Leigh Kilarski, a local 11-year-old who, on his way to a hockey game, was killed in a car accident.

Time hasn’t been kind to the memorial, which the plaque tells me was funded by Leadbeater, Peter Pocklington and the Alberta Foundation for the Arts.

The chubby child on hockey skates is rusted. The faded blue columns are uneven, as the crumbling concrete pads have settled into the ground at different rates. A yellow soccer goalkeeper flies in the air, a metal disc clutched in her grasp.

It’s a stark lesson that sculptors can lose their work or see it diminish. Time is not always kind to the artist. Even though the elements haven’t been kind to the work in Cardiff Echoes, it still stands.

But, other pieces aren’t in public view. For decades, his bright, brassy “Fantasy Chariot” greeted those who walked through Entrance 45 of the West Edmonton Mall. But, as the mall was renovated, the art was taken down.

Sheri Clegg, spokesperson for the mall, says that “Fantasy Chariot” is safely stored away.

“The statues that were removed from our common areas, including ‘Fantasy Chariot,’ are in storage. They will be repurposed – that could be here at WEM or at one of our other properties.”

As well, Leadbeater’s “Aurora’s Dance,” a 440-foot long work of painted steel that was on 104th Street, is no longer in public view. Leadbeater completed the $85,000 commission in 2000. The two sections have moved over the years. When ground was broken on the Icon Towers, one section was moved to a park on 102nd Street just south of Jasper Avenue. When work began on the Fox condo project, another section was moved. Now, both sections are in storage.

“We want to keep it downtown,” says Jim Taylor, executive director of the Downtown Business Association. “It needs some paint work, some restoration. But we do hope that, when it’s ready, that it remains here. It was commissioned to be downtown.”

But other pieces can still be seen in and around the city- and are well preserved.

Leadbeater’s “Genesis” can still be found at the Citadel. His “Ocean Moon,” erected in 2001, is still on the patio of the Marriott Courtyard Downtown, with its distinctive D shape and what looks like lunar craters keeping the patrons company.

His ornate, decorative cross, which still acts as the centrepiece for St. Michael’s Cemetery, was installed in 1975. It was commissioned to commemorate Ukrainian veterans of the Second World War who fought against the Nazis.

Leadbeater still remembers anxiously watching as workers put the cross in place. Cables were lowered to support the piece, to make sure it would stand upright.

“I was sitting in my car, with the door open, listening to the opera from New York. And a man came up to me and asked ‘did you do this?’ And I said yes – and he said, ‘Jesus Christ, it’s beautiful.’ And it just made me feel so good.”

Roy Leadbeater isn’t retired. In a few years, he’ll be celebrating his 90th birthday, but he still paints and designs. He doesn’t cast his work anymore – but his partner, Wes Leonard, does the heavy lifting. They split the proceeds 50-50.

He’s now married to his third wife, Evelyn. Betty was with him for 30 years, but after she passed away, he met Evelyn through Lifemates, the online dating site. They’ve been married for eight years. When they first dated, Leadbeater remembered that she worked at a firm from where he got parts for his Expo ’67 commission. They had actually crossed paths four decades before they were married.

Evelyn also looks after the financial affairs – because Leadbeater admits he was always bad when it came to cash.

“To me, money was something that when you had it, you had it. She [Betty] was appalled at my bank account. Evelyn is also very sharp. I was very fortunate in that I always married the right women.”

For a man who was abandoned as a child and didn’t get the formal art education he so badly wanted, Leadbeater won’t allow you to think for a second that he is a tortured artist. In fact, he feels that life has been very good to him.

“I’ve always said someone up there likes me, because good fortune has always come my way.”