When Gurcharan Bhatia was a member of the Canadian Human Rights Commission, he’d regularly go to Ottawa for meetings. And, close to the building where the Commission was housed, there was a tower under construction.

It inspired Bhatia. He suggested a novel concept to his fellow commissioners: that they tackle a new human rights issue each time a new floor went up at the construction site down the street.

What did they tackle? Pay equity for women; laws that would not allow airlines to discard flight attendants when they got older, the right for Sikh RCMP officers to wear turbans, and the rights to clean water for Indigenous communities.

Bhatia sat on the commission from 1989-1995. As a citizenship judge, he’s sworn in more than 40,000 new Canadians, representing about 200 different nationalities, cultures and languages. He founded the Alberta Link newspaper in Edmonton back in 1980, which was aimed at bridging cultures and communties, immigrants and citizens. In 1982, multiculturalism was entrenched in section 27 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Bhatia has been a staunch lobbyist for that — and he met with Laurence Decore (a dedicated Liberal) and then-premier Peter Lougheed to make the case.

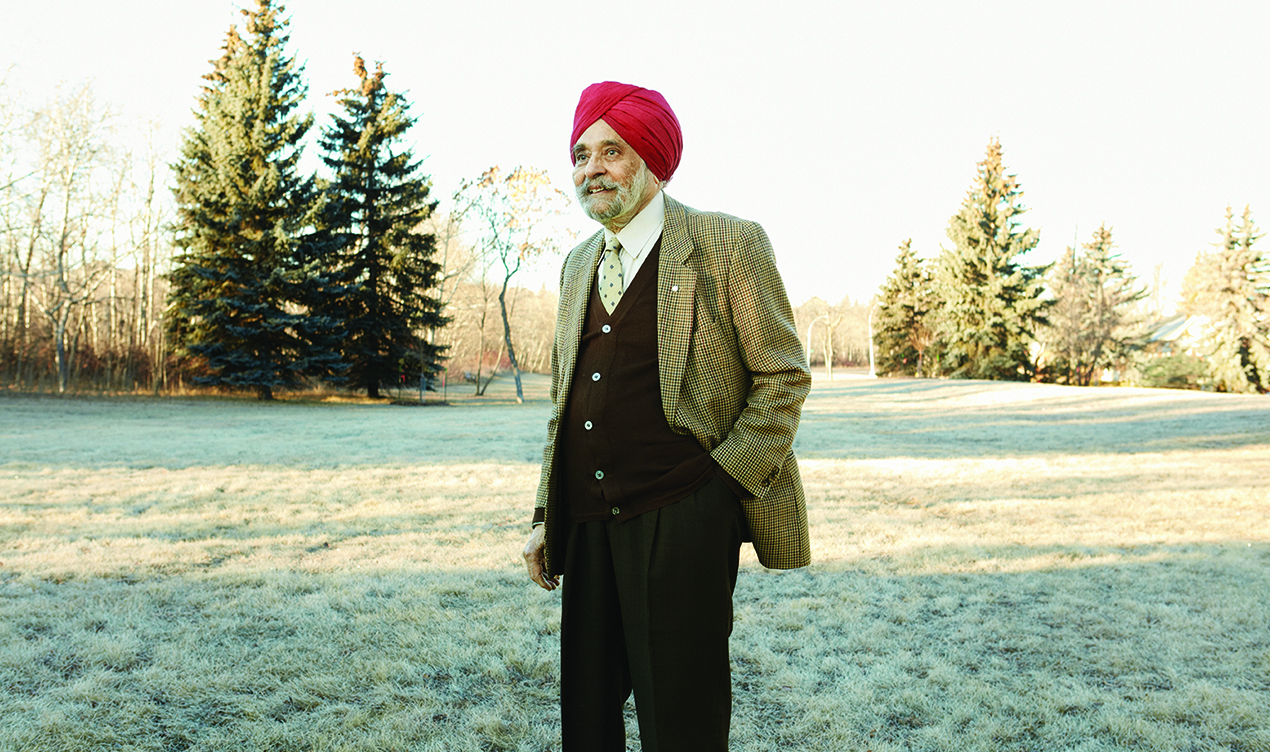

It’s an exhaustive résumé. And you’d be hard-pressed to find a prouder Canadian than him. Close to his Blue Quill home, you’ll find a park named for him and his late wife, Jiti, who he says “is still with me every day.” In his home, you’ll find pictures of him standing with the late South African civil rights leader, Desmond Tutu — one from his visit to Edmonton in 1998 celebrating the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights, which Bhatia chaired, the other from an interview with Bhatia when Tutu passed away.

But, even though he’s 92 years of age, he is still working with Canadians for a Civil Society, an organization he helped found in 2010.

“I am in my 90s, but I still have a lot of energy. Canada is a great country, but it can be even better.”