He dreamed of wearing the colours of his favourite team. Except those colours were black and gold. He dreamed of being on a football field, not a sheet of ice. He wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps, and play for the hometown Hamilton Tiger-Cats.

“I was always a huge football fan. I wanted to play football since I could learn how to walk,” Nurse says. “I saw the pictures of my dad playing for the Hamilton Ticats, and I’d go to the game and picture myself being a receiver for the Hamliton Ticats.”

The one problem? His dad, Richard, who played six seasons in the CFL, told his son that he would be allowed to play hockey and lacrosse, violent sports in their own rights, but the pigskin was verboten.

“I definitely wanted to play football, but my dad wouldn’t let me play football,” Nurse laughs. “I went to him multiple times, and he said it was too violent of a sport. But he let me play hockey, where you can fight and hit anyone whenever you want. In hockey and lacrosse, there’s a lot of violence in those sports some days, too.”

Adding to the irony of the football ban was the fact that Nurse’s uncle is Donovan McNabb, who amassed more than 37,000 passing yards in an elite NFL career.

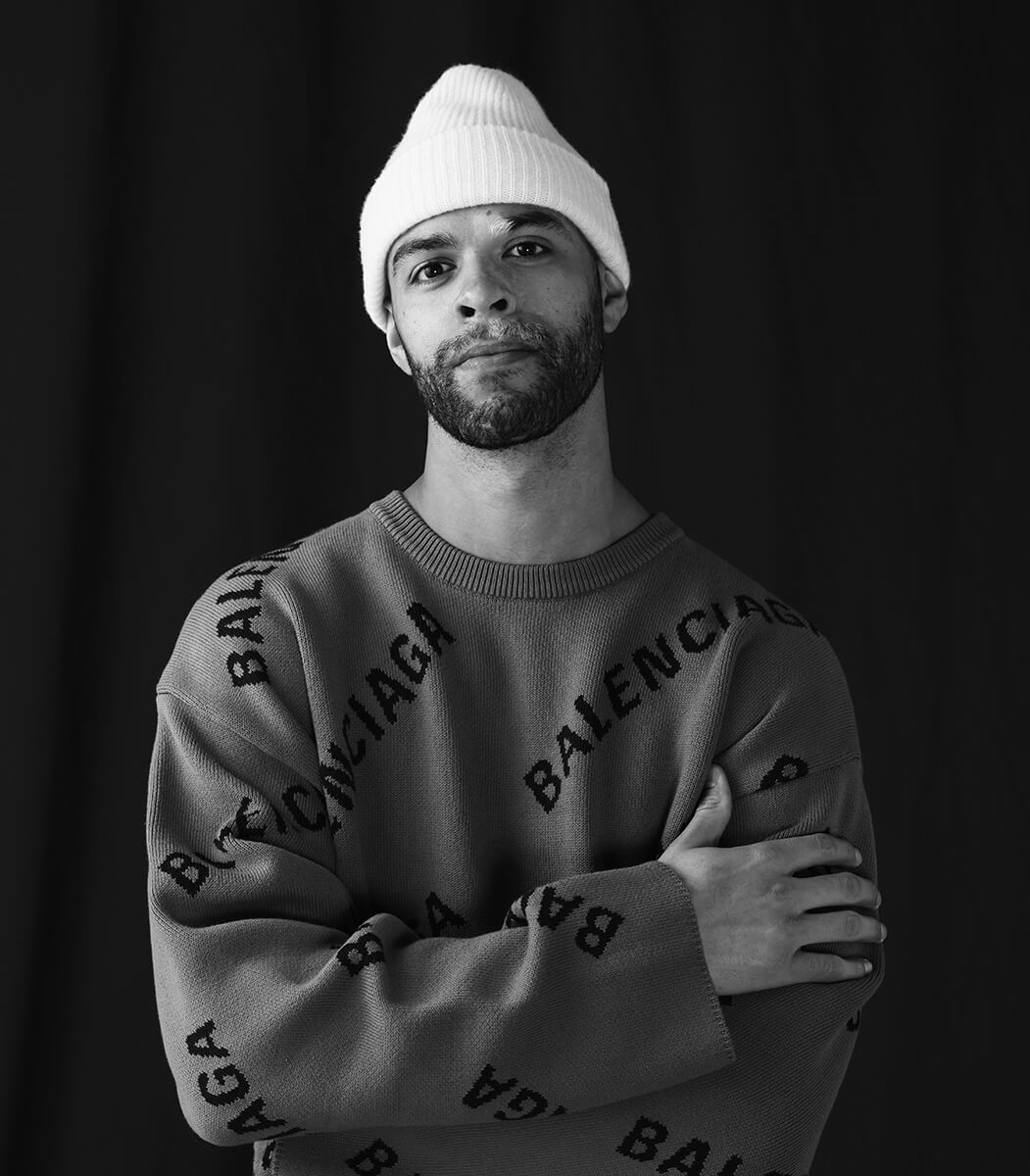

But, hockey was the right choice. This past summer, Nurse signed an eight-season extension to his contract, which will see the Oilers pay him $74 million over the life of the deal. That extension kicks in at the start of the 2022-23 season, so the deal essentially commits Nurse and his young family to Edmonton for nine years.

Taken with the seventh overall pick in the 2013 draft, Nurse has already played more than 450 career games as an Oiler. He’s established himself as the No. 1 defenceman on the team, and he’s been in Edmonton so long, it’s easy to forget that he’s only 27 years of age. But, though he’s already been in this city for the better part of a decade, it wasn’t until the long-term deal was signed that the attachment between himself and the Oilers got the feeling of permanence. Before that, he signed two short-term bridge deals, and unrestricted free agency — where he could have tested the market — was looming.

Playing in Edmonton is not easy. It’s a city where the legacy of the best-ever team to play the game — Wayne Gretzky and co. of the air-hockey 1980s — casts a shadow on anyone who wears the oil drop on his chest. Over the years, I’ve had many Oilers players tell me that playing hockey in Edmonton is like playing football in Green Bay, Wisconsin. It’s one of the smallest markets in the league, but it’s a place where even a guy who was called up from the minors the day before is recognized when he goes out for milk. It’s a place where it’s much harder for the players to go out and about than, say, New York or Los Angeles. It’s a place where hockey is magnified. And, so, there is far more pressure to play hockey in Edmonton than in a big American city — just like playing football for the Packers carries more pressure than the majority of other places in the NFL.

“I think, as a player, to have the support and the fans and to be a part of a community that cares a ton about hockey, it’s a huge advantage,” says Nurse. “It’s something that you want, to be part of a market that cares about this game. But there’s a curse to it too, because you can win five games in a row, but if you then lose four games in a row, you hear ‘Get rid of everyone.’ That’s just how this city works.

“They [the fans] care a lot, and they’ve been disappointed in this team for so long. And you talk to fans, you talk to season ticket holders, and they’re not season ticket holders from just five years ago. They’re season ticket holders from the ’80s and ’90s. They eat, breathe and live the Oilers… the best part of it all is that we have die-hard fans who just love this team. They get mad when we don’t have success, and that’s just the give and take of a strong hockey market. But I wouldn’t wish to be somewhere where there are only 8,000 fans in the stands.”

Nurse says that, while he enjoys his quiet time, he’s built a lot of great friendships in Edmonton, which he unabashedly calls his second home.

And, after the long-term deal was signed, Nurse made the decision to partner with Free Play for Kids, an organization founded by Top 40 Under 40 alumnus Tim Adams that offers sports programming to disadvantaged children. Originally called Free Footie, the program began by creating chances for kids to play soccer, and one of the players it served in its nascent days was someone named Alphonso Davies — who is now regarded as the best left back on the planet, as he stars at Bayern Munich.

Now, the program has expanded its reach to other sports — including hockey, basketball and flag football — and Nurse has pledged his support to get more kids from marginalized communities onto the ice.

“I’ve always tried to look for causes and charities to team up with that have the same values I have,” says Nurse. “This is one of the first times I’ve seen a program, a charity, and said, wow, this lines up with everything I want to be a part of. It’s sport, it’s very inclusive, it brings in a lot of immigrant families. My dad was an immigrant to Canada [Richard was born in Trinidad and Tobago], so, that hits home for me. It gives people the chance to feel part of a community — people who may feel like outsiders in their everyday lives.”

Hockey, like many other team sports, is suffering from a decline in registrations that began before the pandemic, but has only been accelerated through the COVID years. Canada has only half the number of registered hockey players today than it did in 2014-15. The newly formed Hockey Diversity Alliance is looking to create more opportunities for players of colour. A pilot project, in conjunction with Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment, will provide 1,200 playing spaces for players in priority communities.

It will only be through being more welcoming to new Canadians and the BIPOC community that hockey will start to grow again.

“If you don’t see people like you doing the thing, that thing doesn’t seem attainable,” says Adams. When he first met with Nurse, he was simply amazed by the passion Nurse showed for the project — and he saw right away this wasn’t a case of an athlete supporting a charity simply as a PR exercise.

“It feels like we’ve been fighting for a long time. It’s nice to finally have someone like Darnell in our corner and willing to take the gloves off with us,” Adams says. “In every meeting we’ve had, his authenticity shines through.”

Adams says costs and transportation issues make up only a fraction of the reasoning that kids in need can’t access sport. There are issues of culture and race. And having Nurse as an ambassador gives Free Play for Kids “a bigger megaphone” to spread its message.

Kids in the Free Play program will get the chance to be the “Darnell Nurse Captain of the Week” and get the chance to go to an Oilers game.

“I couldn’t even imagine going to school and to know that your parents, or whoever you came over to Canada with, they’re doing every-thing they can to supply your everyday needs,” says Nurse. “And, on top of that, you’re just try-ing to fit in. That’s a lot of adjusting to do. This program gives not only an outlet to play and get support, but you see there are a lot of other people in the same position. Just looking at the charity as a whole, the program as a whole, it was kind of a no-brainer to be a part of.”

Before striking a partnership with Free Play for Kids, Nurse created a scholarship program at St. Thomas More Catholic Secondary, his old Hamilton high school. Two $40,000 scholarships will be awarded each year to kids who need financial assistance for their post-secondary education, and can show how they’ve overcome adversity to do well in their current studies.

For Nurse, being part of these charitable programs — both at home and in his second home — brings back memories of his childhood. He comes from a family of athletes. Not only did his dad play in the CFL, his mother, Cathy, played basketball at McMaster University. His sister Kia, won two national basketball titles at the University of Connecticut and plays for the Phoenix Mercury of the WNBA. Sister Tamika played basketball at the University of Oregon and at Bowling Green State University. And his cousin, Sarah, just won gold in Beijing with the Canadian national women’s hockey team.

So, that’s why St. Albert-raised Calgary Flames mainstay Jarome Iginla meant so much to Nurse. Last year, Iginla was inducted in the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Iginla told Sportsnet how important it was to have white teammates, and families of those teammates, stand up for him when he was coming up the ranks.

“Yes, there were some incidents where something was going on in the stands…later after the game, you’d hear somebody say something inappropriate and ignorant, and one of my teammates’ dads went over and talked to him. You know, those meant a lot for me, to have that support from my teammates and other families. It meant a ton — it wouldn’t have been the same if it’s my grandpa having to go over and talk to them.”

“It was the best when teammates who don’t look like you stick up for you — and I had that happen on multiple occasions in hockey or lacrosse,” says Nurse. “If I look back, I’m appreciative of the fact that my teammates had my back, no matter what.

“Whenever I look to get involved, whether it’s the scholarships (in Hamilton) or Free Play for Kids, I definitely look back and reflect on some of those instances. At the same time, I look back and see that those instances didn’t change me as a person, they didn’t stop me from getting to the position I’m in today. But, I’m not going to say they made me stronger, because you still sit back and think about them, even today.”

Through his Oilers career, Nurse has teamed with Kailer Yamamoto, an Asian- American winger, and Jujhar Khaira, one of only four players of Indian descent to play in the NHL, who has since moved on to Chicago.

He’s played with Ethan Bear, an Indigenous defenceman who was a fan favourite, but was dealt to Carolina in the previous off-season.

But the fact that we can still count players of colour in the NHL on our hands, well, that is something that needs to change. If it doesn’t change at the elite level, then we will continue to see minor hockey be the shrinking domain of white suburban families who take their kids to practice in their BMW SUVs.

“Hockey has been Canada’s game for so many years,” says Nurse. “And, as a country, we like to brag about how diverse we are and how inclusive we are as a people and as a country. Hockey hasn’t had the same effect, the same look. You look around hockey arenas, they don’t have lots of Black players, players of Asian descent, Aboriginal players. It doesn’t have that feel — there are a lot of white players who play hockey.

“For me, the way to look at it is representation. You look at the NHL, and slowly but surely, the league is getting more diverse. But it’s not at the point where you’re watching hockey every night and saying ‘There’s someone who looks like me, that I can see myself being one day.’”

It’s a chicken-and-egg thing. If kids watch a game and see opportunity rather than barriers, there’s more chance they invest themselves in the game, both as players and fans. This will lead to more BIPOC players in the NHL, who will inspire more kids. But, to Nurse, it’s not just about giving kids who can’t afford to play some ice time on Sunday afternoons. It’s about creating paths for these players, that those who show promise — like Alphonso Davies in Free Footie — can move up.

“A big part of it is representation, and that’s not only the grassroots part of the game, but also giving some of the better talent who are diverse the same opportunities when they’re coming up,” says Nurse. “When they’re 13, 14, 15, 16 years old, getting the skills trainers and the coaching so they can have the same opportunities to get to the next level. That’s where my mind goes. Having those kids have access to those types of resources, to be able to push to the next level, will make the league more diverse. And that will mean that more kids who look like me, who look like Kailer Yamamoto, who look like Jujhar Khaira, they’re going to want to play the game, as well.”

Nurse is going to continue to call Edmonton home for the better part of the next decade. And, while the charitable endeavours are important, he will be judged by how well he and his high-profile teammates, Connor McDavid and Leon Draisaitl, will do on the ice in their time together. With the long-term contract in place, Nurse feels some distractions have been removed from his life. There is a long-standing school of thought that players on short-term deals give more effort because they’re always playing for their next deal. But Nurse says that isn’t true.

“I’ve played through two bridge deals, and now I have a long contract. I probably put more — I wouldn’t say pressure is the word, say, attention to detail — now that I know I am locked in for a long time. I want to make this the most special nine years of my playing career. I’ve gone through two seasons where there’s uncertainty, where you’re playing for a contract and, honestly, I’m more hungry now that I’ve got the long contract. Each and every night, I have to prove why I deserve to be here for that long and why they’ve given me this opportunity. And, whenever an owner and a general manager put that kind of belief in you, as a player, it makes you more hungry to want to bring home a Cup.”

This article appears in the April 2022 issue of Edify