Newport Coast is a community of gates and estates. Only about 20 minutes south on the expressway from Anaheim, depending on the unpredictable southern California traffic, it feels like it’s a world away from the sprawling Los Angeles suburbs.

The In ‘N’ Out Burgers are nowhere to be found. There are no 7-Elevens, no Sizzler steak houses, no signs in Spanish. The main street winds through a valley, with perfectly manicured public grasslands off to the side. On the tops of the canyons above the main street, the backyards of the wealthy loom above anyone who’s paid the $2 toll to get off of Highway 73 and into the town.

At each traffic light, there’s a choice. Turn left into a gated community, or turn right into a gated community.

But, somewhere on the end of one of these winding roads, in a mansion that sits at the edge of the canyon, you’ll find an interesting slice of Edmonton. On a wall of Bill Comrie’s office, you will find a certificate that confirms Comrie as a Chancellor and Principal Companion in the Order of Canada. Around it are news clippings, photos and plaques, celebrating his work in helping to launch the Mazankowski Heart Institute and the Stollery Children’s Hospital. Then, you look out the window to a scene that is not Canadian in any way; past the palm trees, past the putting green, over the canyon edge and down towards where the bright blue of the Pacific Ocean meets the pale blue sky.

Comrie places a napkin on his desk. The napkin is covered in numbers, scrawled in ink.

“It’s my first budget,” he says.

It was on this napkin that he mapped out the finances of the first Bill Comrie’s Furniture Warehouse. Opened in 1971, two years after Comrie turned down an invite to go to training camp with the Chicago Blackhawks, that store became the seed for the Brick furniture empire. Comrie went into the family furniture business after his father suddenly passed away. He took over the store and gave up a chance at a pro hockey career. But Mike and Paul, Bill’s eldest sons, did make it to the NHL. Mike, now 33, played 11 seasons, until chronic hip problems forced him to retire from the game. At an age when his former peers are negotiating multi-million-dollar contracts, his bad hip now limits him to playing in men’s-league games in Los Angeles. Paul, now 36, played 15 games with the Oilers in 1999 before the effects of a concussion forced him to prematurely end his career and go into his dad’s furniture business.

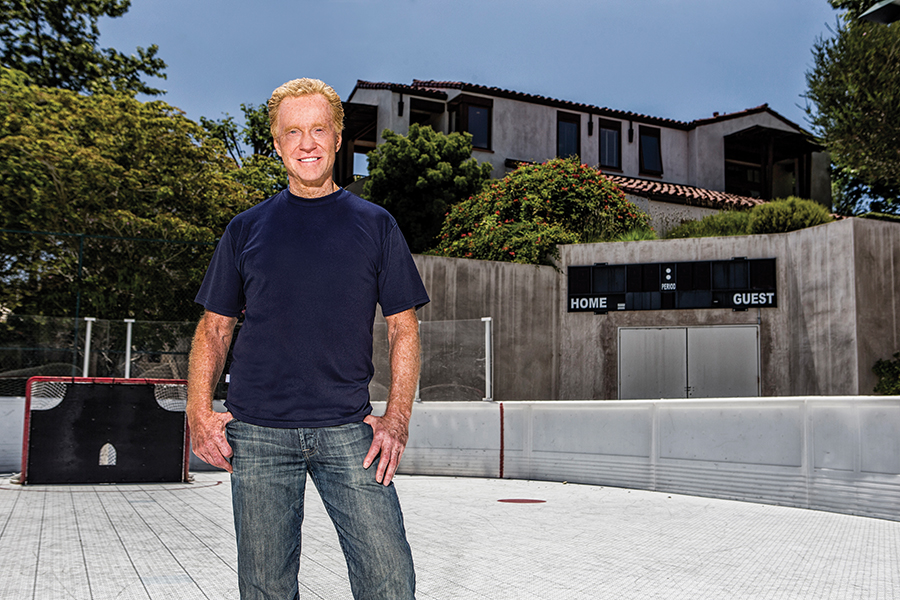

Alongside Mike and photographer Curtis Comeau, I walk across the lawn from Bill’s office to the main house, past the full-size roller-hockey rink. It’s there we find Eric Comrie, Mike and Paul’s 18-year-old brother. In a month, Eric will be selected in the second round of the NHL draft by the Winnipeg Jets. He could be the third Comrie kid to make it to the NHL.

But, today, Eric is bending his knees, a hockey stick draped across his back. Watching him is Andy O’Brien, the Calgary-based training guru who has worked with the likes of NHL superstar Sidney Crosby and world champion figure skater Patrick Chan. O’Brien knows that we’re coming to visit Eric; but both trainer and Bill have made it clear to Eric that his training session won’t be cut short because an interviewer and photographer are here from his hometown of Edmonton. Eric will talk once his workout is done.

As we are introduced to Eric, Mike points to the outdoor rink.

“It gets pretty heated in there,” he says.

“From the sun?” asks Comeau.

“No, us.”

And that’s the thing. There’s a competitive fire inside all of the Comrie boys. Mike says that, just the day before, the boys were trash talking with their dad over a putting competition on the green. They’d compete over tiddlywinks. It’s part of their DNA.

The sliding doors to the workout room are wide open. Inside the home gym is a collection of art the Hockey Hall of Fame’s acquisitions branch would love to know about. There is Wayne Gretzky, posing with the Stanley Cup, crouching next to two kids whose smiles jump off the photograph. Paul and Mike clearly can’t conceal their excitement. There are autographed jerseys, medals and news clippings – the baubles and awards from Paul and Mike’s hockey careers.

This is where Eric spends the off-season, as he recovers from a hip injury that cut his previous junior-hockey campaign short. He knows that his road to the NHL will be a long one. Goalies take a long time to develop. And he knows that he will be spending the next season not in Winnipeg, but back in the Western Hockey League, riding the buses across the Pacific Northwest and the prairies as a member of the Tri-City Americans, a major junior team based in Kennewick, Washington.

It’s a heck of a long way from Edmonton. Or Newport Coast.

“The draft only means that your rights are owned by a team,” says Eric, who has put on a blue dress shirt after his workout is done. “It doesn’t mean you have a spot. Once your rights are selected by a team, that means you have to work twice as hard if you want to take the job of someone like a Roberto Luongo, Marc-Andr Fleury or a Carey Price.”

Riding buses on cold winter’s evenings across Washington, British Columbia and Alberta seems like a world away from the Comrie mansion. And, this year, Eric will be joined by Ty, 16, the family’s youngest hockey phenom. Like Mike and Paul, Ty is a forward.

“I can’t wait to play with my brother [Eric] ,” says Ty. “Our success, it comes from parenting, learning to live with hard work, playing the game right way.”

If all goes according to plan, Bill will be able to boast about four kids who made it to the NHL; it’s a pretty fair trade for a man who had to give up his shot at the big leagues.

And that’s saying something. It would be easy to write off the Comrie boys as rich kids, children of privilege, who ride on the coattails of their entrepreneur father. But that’s not the way dad raised them. You’d think it would be easy for Eric and Ty to grow up in California and ignore their Edmonton roots. They live in a home where their brother Mike and his wife, Hilary Duff, are regular fixtures. There is celebrity and there is wealth. But Eric sees just the opposite.

“Dad always taught us the value of money, and that you have to work very hard in order to get success,” says Eric. “We know his success was based on hard work, and it’s something that influences me every single day.”

And Eric has a sense of place. He may be spending the off-season at the Comrie’s California home but, like his father, he regularly gets back to Alberta. In 2011, he represented Alberta at the Canada Winter Games. At the 2012, World Under-17 Hockey Challenge, he played for Team Pacific, which was made up of kids from Alberta and British Columbia.

Eric was born in Edmonton, and that’s where his allegiances lie. In fact, his dad says the family members have no interest in dual citizenship. They want to be seen as Edmontonians who spend time in California, not Edmontonians who want to become Americans.

“I really do find myself in two places,” says Eric. “I love living in California. I mean, how do you not love it, it’s 80 degrees [Fahrenheit] here every day. But Canada has been great; I have been lucky that I have grown up in two exceptional places to live.” Eric, though, doesn’t just get advice from his dad. He has his siblings to look up to. Eric and Ty’s mother is Roxanne, Bill’s wife of 19 years. Bill remarried after his first wife, Theresea – mother to Paul, Mike and their older sister, Cathy Robinson – lost her battle with cancer. But if there’s one thing the Comrie clan hates, it’s when the term “half-brother” is used to describe Eric and Ty’s relationship to Mike, Cathy and Paul. They are brothers and sister.

“I feel like we are close friends, even though I was 20 when Eric was born,” says Cathy, who is up from Edmonton with Paul, visiting the California home. “Ty and Eric are uncles to my children but they seem more like cousins.”

Eric became a goalie at a young age because older brothers Mike and Paul needed someone to help them practice.

I first met Eric in 2005, at the West Edmonton Mall Ice Palace; he was the goaltender for the rep LA Hockey Club at the Brick Invitational Super Novice Tournament, one of the biggest annual events for nine-and 10-year-old elite players.

“They needed someone to shoot on, so they put me in net,” he said back then.

But as much as the put-the-kid-in-net is a cliche when it comes to Canadian hockey families, the fact that Paul and Mike had to deal with hardships at the NHL level offers sombre lessons for their kid brother. Paul, who went to school at the University of Denver, was drafted by the Tampa Bay Lightning in 1997, but never played for that team. His rights were traded to Edmonton later that year. Paul finally got his shot to play NHL hockey in 1999, but a severe concussion cut his 15-game career oh-so-short.

Mike, though, was supposed to be the prodigal son, the hometown hero whose name was destined to be raised to the rafters. A junior-hockey and University of Michigan scoring star, the kid who went to Jasper Place High School was signed by the Oilers on New Year’s Eve, for the 2000-01 season. For two and a half years, he was the face of the Oilers – but in 2003, an ugly contract dispute with then-general manager Kevin Lowe, fought through the media, saw Mike’s reputation as the squeaky-clean hometown hero get dragged through the mud. Mike held out for 30 games before he was dispatched to Philadelphia. He stayed in the City of Brotherly Love for only a couple of months before being sent to Phoenix. And, when he came back to Edmonton on road trips, he was booed mercilessly by Oiler fans who used to wear his jersey on their backs.

It wasn’t easy on the family, either.

“Definitely, when Mike got booed when he came back, it wasn’t a good feeling,” admits Paul. In his first game in Edmonton as the member of a visiting team, Mike was laid out by a thundering check from Jarret Stoll. When Mike, wearing the Phoenix Coyotes’ jersey, hit the ice, the crowd roared in appreciation. Before Mike left the city, rumours were passed along on fan blogs and message boards about him possibly having an affair with a teammate’s wife. It was unfounded – and, as any athlete will tell you, it’s fair game to take issue with him for on-the-ice issues, but the personal life is off limits. When the fans went into lynch-mob mode, it didn’t sell Edmonton as a city that’s an attractive place for players to call home. In a city that has a storied hockey history, it wasn’t our finest hour.

Mike would later go to Ottawa and the New York Islanders, before coming back to play a season in Edmonton in 2009-10, a chance for him to bury some personal demons. It was in 2010 that he and Duff married. He then went to Pittsburgh, but his hip issues got to the point where he had to hang up his skates.

“I think I’m not going to tell them [Eric and Ty] how to live their lives, but we do have conversations about playing hockey,” says Mike. “For a player today, staying healthy is half the battle. My dad did a good job with all of his kids, laying a good foundation. Family comes first. Even though we have been successful with hockey, we try to stay true to the values he’s instilled in us.”

“Mike was awesome laying out the choices for me between junior hockey and college,” says Eric of his older brother. “He laid out all the pros and cons. He didn’t make the choices for me, he just wanted me to understand all the options.”

As we talk, Duff watches over her and Mike’s infant son, Luca. The little boy is already showing that he has some of the athlete genes from his dad; by the time most kids are still getting comfortable with crawling, Luca was walking.

“Luca was 11 months and he saw all of his cousins walking, so he decided to get up right there and walk,” says Duff.

But Mike is insistent that neither his son nor Duff be photographed. It’s clear that the paparazzi is one part of the Los Angeles tradeoff he hasn’t enjoyed. He doesn’t enjoy a walk with his family becoming the subject for photographers. Just Google the words “Comrie” and “Duff” and you’ll find hits such as “Hilary Duff and Mike Comrie, Shopping in LA!” or “Family day out! Hilary Duff and Mike Comrie trade holding baby boy Luca as they head out for an early Father’s Day lunch.”

Mike is now a principal in HPM Partners, where he advises NHLers on how to make their investments and have cash left for when their careers are over. Too often, Canadian middle-class kids go from prospects to millionaires, too fast, too young – and they squander their cash through big living or fly-by-night investments. Friends show up and start pressuring the player for cash. And the player feels he has to pay for all the meals when he goes back to his hometown to see all his buddies. Mike is a unique position; he understands big business through his family, but relates to the day-to-day life of the NHL player.

When he was first an Oiler, he looked unsure in front of the cameras. There was never a sense he was comfortable with being thrust into the spotlight.

“Every player is different. Some players, some families enjoy it (playing in your hometown),” says Mike. “For us, our family did a good job raising us as normal as we could. We had a normal family life in Edmonton.

“But when I look back at it now, I can say some of it was definitely a challenge. Not every day are you going to wake up and feel amazing. Not every day do you want to go to the grocery store and talk hockey. Then, when things went the other way, they [media and fans] did want to make me look bad. There were false rumours. And then I began to understand that was part of the business of sports. But there were times that the Sun said something about me and I felt the kitchen sink was being thrown at me. I was 23 at the time, and sometimes it was too much to handle for someone my age.”

Playing hockey in Edmonton is infinitely tougher than playing in Los Angeles or New York; in Edmonton, everyone recognizes even the player who just got called up from the minors. There’s nowhere to hide, no escape from hockey. In New York or Los Angeles, you don’t play the most popular game in the city, you blend into the background.

Now, sitting on a veranda overlooking the Pacific, it’s clear that marriage and parenthood have greatly changed Mike. He speaks more easily, even when I have the recorder on and the notebook out.

“Any parent tells you that when you have a kid, it’s an amazing experience. It was even better than that for us. When you have a child, you can look back at your life and think how selfish you can be. And it made me realize that what my dad was trying to pass on to me were life lessons. There was a time Paul, my dad and I were on a fishing trip. We were trying to catch as big a fish as possible. And we talked about who would catch the biggest fish? My dad or my brother? And my dad said he’d be happy to catch the big fish, but he’d be happier if his son caught a bigger fish than him. Of course, you want better for your own kid.”

Bill Comrie wanted better for his kids, but he didn’t want that to come from privileged lives. They didn’t go to private schools.

Cathy recalls when she was passionate about dance, while attending Ross Sheppard High School. Her father found out she would be onstage as part of a show. His daughter explained to him the show wasn’t for parents to see – it was a closed performance. But Bill wasn’t going to let that stop him from seeing his daughter on stage.

“So, I went in and then I asked the sound man in the back if I could just sit and watch,” says Bill with a smile. “So, I asked Cathy how it went, and she said ‘fine.’ And I asked her, ‘what about when the male lead slipped?’ And she wondered how I knew that.” Bill says that even when the Brick was his full-time job, being at the head of a furniture empire worth in the hundreds of millions, the kids never took a back seat. He never wanted to be an absentee dad, so consumed by business that he’d miss the special events in his kids’ lives. And he credits Roxanne for being a rock in the family after their marriage.

“I think I spent a lot of time with them growing up, I tried to give them as much support as I could,” says Bill. “Theresea and, then, Roxanne, were there for them. For 19 years now, Roxanne was there, and she was there for Paul, Mike and Cathy growing up. Roxanne had a successful business – she ran Sheer Expressions, which had 16 people. She knew how to run a good business. And now [she] has cooked for us and looked after us all for almost 20 years. I don’t know how to cook. I think I made a sandwich, once.”

And, with Eric and Ty on the buses in the Western Hockey League this winter, Bill and Roxanne plan to make lots of visits to arenas across the prairies and the Pacific Northwest. They are already planning their itineraries. Just like when he watched Cathy all those years ago, he’ll appraise his sons’ progress from the background.

Paul’s business career also blossomed. After hockey was done, he moved up the Brick’s corporate ladder, carefully prepped to become the principal in the family business. He rose to the senior vice presidency of the Brick, and was involved with the 2012 sale of the furniture empire to Leon’s – a deal worth $700 million.

As part of the deal, the Brick retained its identity and its Edmonton head office.

Bill is matter-of-fact about the deal: “They made me an offer I couldn’t refuse.”

“Really, not much has changed,” says Paul, who kept his vice-president position after the sale. “We have some meetings coming. But both companies are being run independently. I think it was in Leon’s interest, too, to keep the Brick in Edmonton. One of the reasons they paid a premium for the brand was for the employee base here in Edmonton.”

The Brick name also carries on through the Brick Sports Central, which Bill notes annually gives out 11,000 pieces of sports equipment to needy Edmonton kids. It’s yet another achievement that Comrie can put on that wall in his office.