photography by Paul Swanson

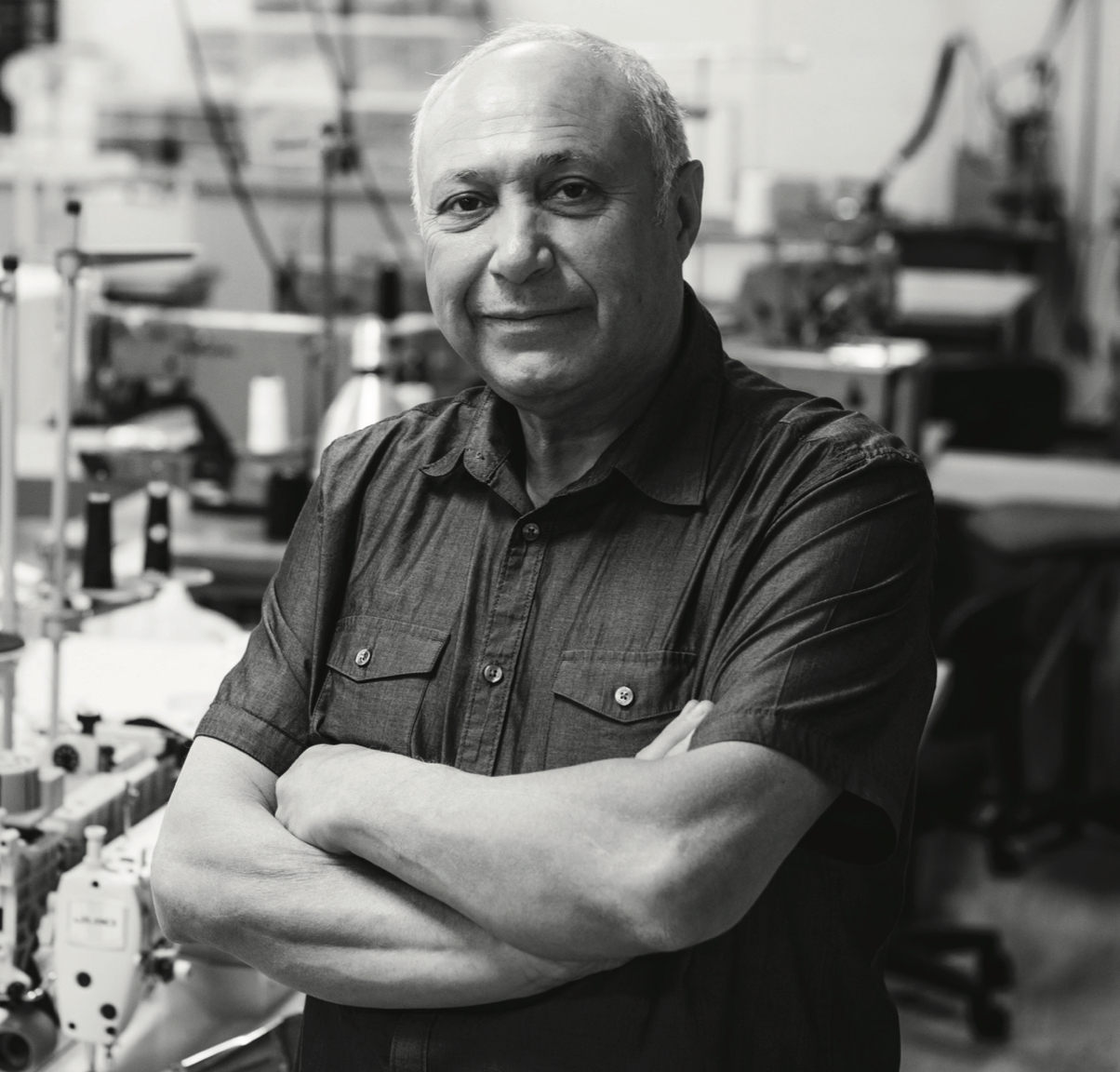

Edmonton has a culinary secret under its hat, and that secret is Claude Buzon.

Buzon – once a celebrated chef in the Edmonton culinary scene who helmed kitchens at restaurants like The Great Escape, La Boheme and the eponymous Claude – is the owner and CEO of Chef’s Hat Inc., a manufacturer of disposable chefs’ hats and other kitchen apparel headquartered in a northwest Edmonton industrial park. From its 15,000-square-foot facility, Chef’s Hat supplies hats, jackets and pants to restaurants and culinary schools around the world.

As such, the job requires a lot of travel. The company has distributors in Las Vegas; Provost, Que.; Winnipeg; and France. Last October alone, Buzon had meetings in Toronto; London, England; and Reykjavik, Iceland. But despite doing business across the globe, he has never dreamed of moving the base of his operations away from Edmonton.

“I’ve always loved Edmonton. From the minute I arrived in Edmonton, I fell in love with the city,” he says.

Buzon came to Canada from France in 1973, first landing in Montreal before making his way west. He served as the matre d’ at The Sahara, along Groat Road near Westmount, for two years before he and two partners bought The Great Escape, which was already on a list of the 10 best restaurants in Canada compiled by Cosmopolitan magazine.

After five years of success at The Great Escape – diners were making reservations six months in advance to get one of the restaurant’s 32 seats – Buzon opened a new restaurant, Claude, at Jasper Avenue and 107th Street, where, being so close to the Alberta Legislature, his regulars included political power players like Peter Lougheed, Don Getty and Ralph Klein. But in the 1990s, after a stint at the Shaw Conference Centre, Buzon decided he’d had enough of the restaurant grind, always working holidays and weekends when he’d rather be at home celebrating with his family.

Luckily, Buzon recalled an encounter he’d had on a trip to Paris years earlier. There, he’d met Daniel Demagny, a chef-turned-inventor who had designed and was selling a unique disposable chef’s hat called La Toque Demagny. In 1996, Buzon bought Demagny’s company and designs lock, stock and barrel, and moved everything to Edmonton. He started with one sewing machine in a 3,000-square-foot warehouse near Oliver Square.”The chef hat was the only thing we were making,” he says. “Now we are 15,000 square feet and bursting at the seams.”