A tipi boldly rose from the middle of Churchill Square, facing the mayor’s office, waiting to be addressed like the multiple human rights issues Lillian Shirt brought to City Council. Shirt, an Indigenous woman originally from Saddle Lake Cree Nation, and her (then) four children were living right in the square after an eviction had left them without a home in the spring of 1969.

When no one would rent to her, she knew she had to do something drastic. Until this point, she had not been heard; in fact, the voices of Indigenous people had been silenced for decades.

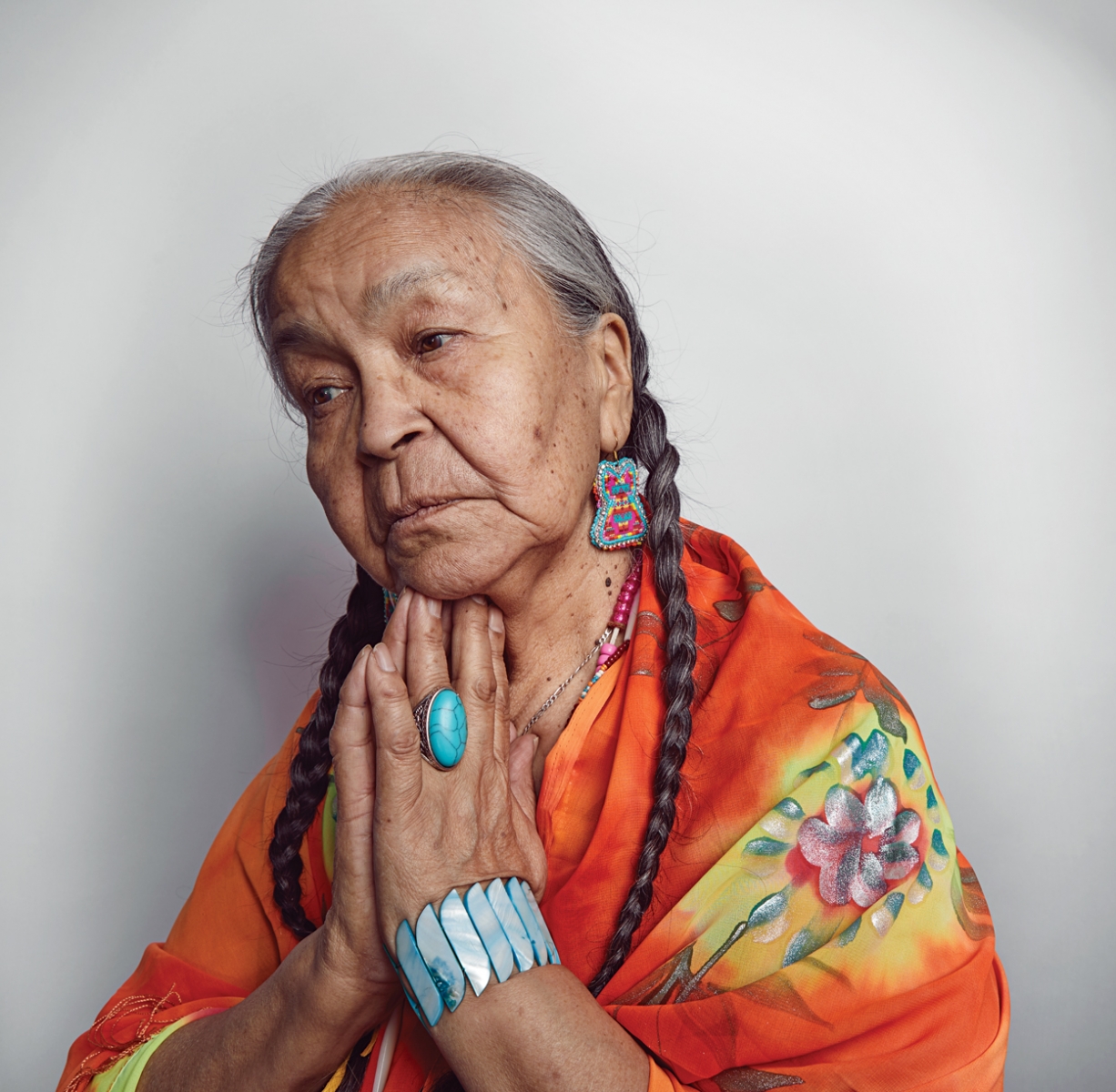

“I was so angry that day,” says Shirt. “Even though we would try to battle against landlords or [problems with] education, the human rights laws were just so lax and useless, we would lose every time. I knew we had to change the human rights laws to see any difference.”

In 2006, Corrine George heard Lillian Shirt’s story when she began working on her M.A. thesis, which focused on aboriginal women activists. George was already invested in the topic – she herself belongs to the Wet’suwet’en Nation, who come from the central interior of British Columbia. The Indigenous group was involved in a landmark court case that resulted (among many significant outcomes) in the acknowledgement of oral history as a valid source of evidence in the court of law. George, who is now regional principal of the College of New Caledonia in B.C., wanted to include Indigenous women’s oral histories in her thesis.

As Shirt began to unravel the many events, which had at that point happened nearly four decades earlier, George became increasingly intrigued. The scene was set in the summer of ’69, and while Bryan Adams had no tie to the occasion, Shirt spoke of a far more popular performer.

The hippie movement was going strong during the ’60s as the younger generation questioned established institutions, while turning a critical eye on long held views of race, gender and class. Shirt was calling for changes to be made to multiple aboriginal human rights issues including housing, women’s rights and education; and she wouldn’t move from her tipi until these issues were addressed.

“This was such an important turning point for aboriginal people … it was the period of change globally when people were beginning to find their voices and in particular aboriginal women, who are starting to become more confident in being able to vocalize their concerns,” says George.

Global icon John Lennon was encouraging that change – he was hosting a series of bed-ins with his new wife Yoko Ono, including one in Montreal that doubled as their honeymoon. In an article for the University of Saskatchewan and Huron University College’s activehistory.ca, George and University of Alberta History and Native Studies professor Sarah Carter claim that Lennon contacted local radio station CJCA from Toronto. He and Ono were staying in Toronto after the bed-in, and requested to speak with Shirt about her protest.

CJCA has since changed owners and the new station, AM 930 The Light, does not have a recording of that interview or any dating that far back. Several former CJCA employees were contacted, but none of them can corroborate the story. Messages and emails were left for Yoko Ono’s press contact, but weren’t returned.

According to George, Lennon asked Shirt about her work and what she was trying to get across with her protest. By this time, international newspapers were carrying her story. On the last day of the bed-in, June 2, an article came out in the Montreal Gazette entitled: “Cree woman believes injustice in housing – pitches a teepee.” It’s one of several articles that George believes could have tipped Lennon off to the work that Shirt was doing. As part of her thesis, George cross-referenced Shirt’s story with newspaper clippings to show how the timeline matched up.

George says Lennon asked Shirt what message she wanted to get out to the world; Shirt translated for Lennon some Cree words her grandmother had told her many years ago that spoke of loving, supporting and helping one another, which would lead to peace rather than fighting. It’s a message that mirrored Lennon’s beliefs at the time.

According to George, Lennon asked Shirt if he could use those words – and that Shirt gave him permission. Shirt says years later, she heard the song “Imagine” on the radio and it reminded her of the interview. There is no certain way to know if Shirt provided any inspiration for “Imagine.” The lyrics are only similar to her grandmother’s words in broad strokes, and the song came out in 1971 with Lennon always saying it was influenced by poems in Yoko Ono’s book, Grapefruit. But the idea her grandmother’s words could have had an impact on one of the biggest songs of all time continues to make Shirt feel honoured.

While the ’60s were a time of change, it wasn’t an easy decision for Shirt to take a stand. In fact, it was terrifying and a big risk, she says. “I felt more at ease when [my story] went worldwide,” Shirt says, and noted that beyond the international news coverage she had support from then-mayor Ivor Dent. “He thought what I was doing was brave, and that I was helping to put Edmonton on the map,” Shirt says.

When Shirt came to Edmonton in the ’50s, she was a teenager and she was brought to Charles Camsell Hospital from the Blue Quills residential school in St. Paul to be treated for tuberculosis. Not only did many children experience abuse, while being stripped of their cultural identities at residential schools, but places like Charles Camsell Hospital provided segregated, subpar healthcare. Years later, some former patients claim their health problems may be linked to the poor treatments they received years ago at the hospital.

Shirt, however, had a more positive experience at the hospital. She befriended a nurse who paid for her distance learning courses to support Shirt’s love of reading and writing. The nurse gave Shirt a book by Albert Schweitzer that embodied a quote her grandmother often said: “If you have a strong mind, you can do anything.” “As I read about Albert Schweitzer I saw the truth in my grandmother’s quote, and I loved it. It is an amazing book,” Shirt says.

Shirt says while those early years were filled with experiences that stemmed from long-held racist beliefs, at the time she didn’t know why these things were happening. “Racism was an everyday experience. I just didn’t realize that’s what it was. I didn’t even have a label for it,” she says. She recalls a time when she was babysitting for a well-known Edmonton family. She says the children’s father asked her why she walked home instead of taking the bus. Shirt told him that drivers refused to let her board their buses – something she didn’t understand was racism, she just thought that “that was the way it was.” So Shirt says that the father walked her to the stop and demanded that Shirt be let on the bus.

By the time she was 26 years old, Shirt fully understood the implications of discrimination, having seen Indigenous people imprisoned, without proper educational opportunities, and continuing to suffer the effects of abuse at the hands of residential schools without any support. She worried about her own children – she was concerned that they were not learning enough about Indigenous culture and she was even frightened of the possibility of them being apprehended if she did not have a home address.

“My grandmother used to say: ‘When you have pain, turn it around so that you gain by it.’ That has always been my stand on my decisions. Did a lot of people understand that? No, they did not … and that was hard to take.”

One day, Jenny, one of Shirt’s 10 siblings, came to Churchill Square to ask her to end the protest as she worried that it was an embarrassment to the family. But, Shirt says it didn’t take long for her sister to be convinced of the importance of what she was doing – especially when people started to take notice and real change was on the horizon.

Shirt stayed at Sir Winston Churchill Square for a few weeks, and then moved her tipi to the legislature where she could be joined by a few other supporters, including members of the Citizens’ Committee on Housing and Discrimination. In July of 1969, premier Harry Strom’s office began to create the start of a provincial plan for welfare housing.

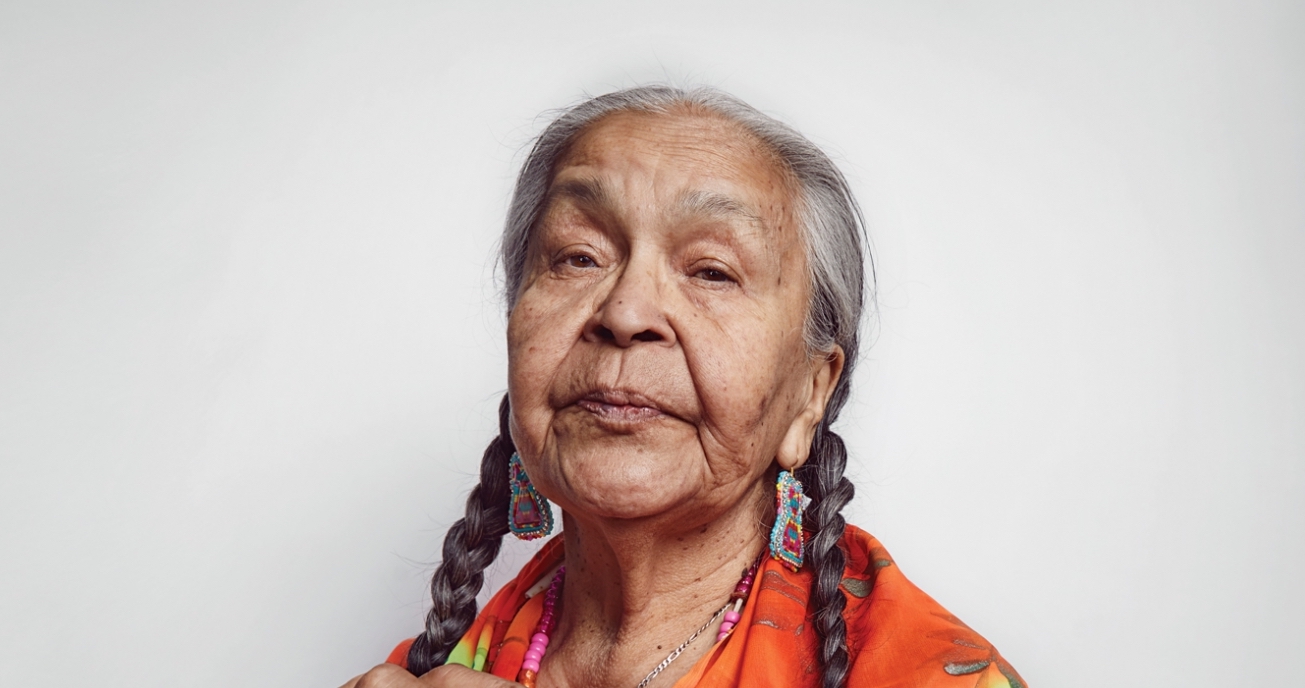

Today, Shirt is 77 and, the day before the interview, she had been volunteering in a classroom of nine-year-olds, speaking about aboriginal culture, language and prayer. A common theme throughout Shirt’s activism work is one of education; she strongly believes in the importance of learning. It’s nearly 50 years after that day she put up her tipi in Churchill Square, and today, students can enter the University of Alberta with Cree to fulfill the language requirement. Even for that victory alone, she says the long days of protesting were more than worth it.

“Sometimes I will go if I hear there is a graduation at the University of Alberta of aboriginal students in law or Native Studies. I will go to there and … sit in the back row and just clap,” says Shirt.

And there have been plenty of other successes. The same summer she lived in the tipi, Shirt wanted to address issues she saw with the prison system. There were a disproportionate number of native men being incarcerated. Shirt knew there had to be more to the story; that systemic discrimination was creating a cycle of problems for these men and that prison was not the solution.

“I was only 24 the first time I visited a prison and I saw these boys and felt so sorry for them. One had been in the army… that’s not going to help him to be in jail. I thought, talk about the injustice,” says Shirt.

So, she got to work creating the Alberta Native Peoples Defense Fund, which helped pay for lawyers for Indigenous people being sentenced to prison. The group organizing the fund rented a house where Indigenous people could take correspondence learning. Shirt strongly believes in the importance of education and has seen first-hand how its access can impact people.

Shirt, along with her sister, Jenny, and other family members, worked on many educational initiatives, including the Prince Charles School, the Smallboy Camp (now Mountain Cree Camp) and Alberta Native Arts and Crafts. The idea behind all three was similar: To ensure that aboriginal children and adults had access to education that included traditional aboriginal beliefs, art and traditions. Prior to that point, aboriginal culture was left off schools’ curricula; in fact, the Indian Act during Shirt’s childhood had criminalized basic traditions including dances or ceremonies.

Shirt was five years old when she was taken away from her family on Saddle Lake Cree Nation to residential school in St. Paul. But she still remembers the many traditions and ceremonies that were carried out in secret on the reserve with the danger of prosecution always there. Things were different at Smallboy Camp, which was Shirt’s home base for five years – several families could come together and dance or sing as loudly as they’d like.

“We didn’t have to hide anymore. But I was still scared and I’d say: ‘What if the cops come?'” says Shirt.

Over the years, Shirt has been able to see changes in issues regarding human rights, housing, issues regarding children and issues related to the rights of women. And, while she’s happy with the way things have been going, she feels like there is always more work to be done.

“It would be good to keep revisiting the laws. When you were small, you probably wore a size six shoe. Now, maybe, it’s a size eight or nine and you need to change. You know, if you try to cramp your feet into that shoe, it ain’t going to work. Same with the laws. They need to be flexible,” she says.