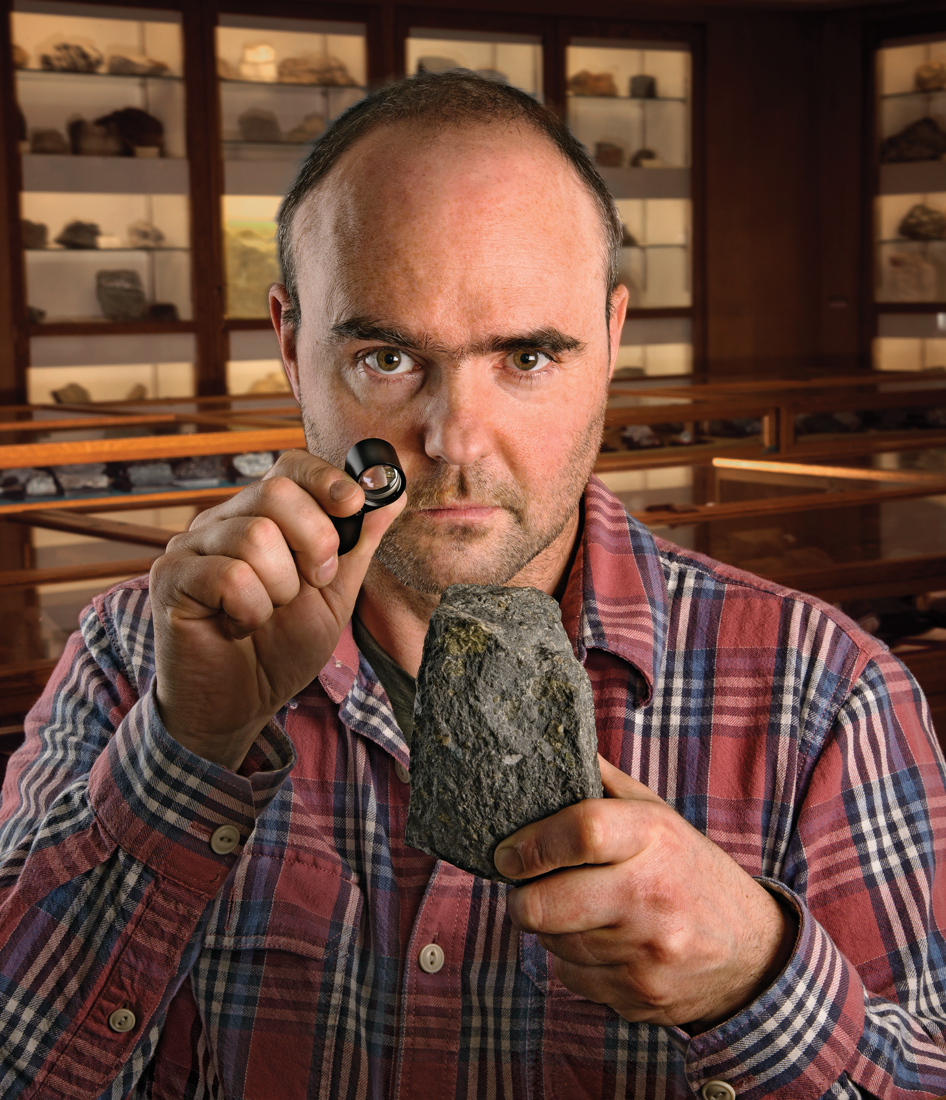

Who: Graham Pearson

Age: 48

Job: Geologist

Experience: He has been chased by polar bears in the Northwest Territories, ostriches in South Africa and a nine-foot-long cobra in Namibia – all while in pursuit of diamonds. As the Canada Excellence Research Chair in Arctic Resources at the University of Alberta, he routinely travels the world gathering samples from deep inside the earth’s crust that tell him how diamonds form, where they come from and how old they are.

His interest in the minerals began in 1986, when he was a graduate student at the University of Leeds, in England, and was assigned to a research project on graphite. But he was quickly seduced by the diamond, graphite’s flashier chemical cousin. Over the past 25 years, he has pioneered a method for fingerprinting individual stones by analyzing their inclusions, or chemical impurities. This helps him determine the actual age of a stone and the area of the world from which it came, in some cases to within as little as 20 kilometres. The model can also help eliminate the blood diamond trade and identify new locations to mine, right here in Canada, where diamond exploration and mining is a $2-billion-a-year industry.

This fall, he opened a $10-million lab at the U of A, where he uses one of only two laser diamond cutters in the country to smash the valuable gemstones, in the hope of revealing even more of the secrets of their origins.

- “A lot of diamonds look like tree rings inside, and those growth rings record a whole history of the birth of that diamond and its life span. That life span can be 3.5 billion years, with periods of growth that can be separated by a billion years.

- “Everybody knows that diamonds are valuable, but it’s their value density that is really amazing. Their value-per-unit weight is orders of magnitude greater than any other material on the planet. When you do the numbers right, diamonds are something like five orders of magnitude more valuable than the next rarest thing. Gem-quality sapphires are usually next. That’s how you can have a diamond that weighs the same as a sunflower seed that’s worth $50,000.

- “Diamonds might be one of the rarest things on Earth, but they are one of the more abundant minerals in the solar system. There is basically a sea of diamonds in outer space. They’re embedded into planetary bodies. When you take apart meteorites you can find these nano-diamonds within them, but they are too small to see or sell.

- “Cubic zirconia is a completely different mineral from diamonds, but synthetic diamonds are real diamonds that are made in a lab. In fact, there are now companies in California and Russia that will make you a synthetic diamond out of the ashes of your dead pet, or your favourite plant, or even your grandmother. They can also make blue diamonds, the rarest of diamonds. Still, I wouldn’t buy a diamond made from a dead pet.

- “These things [natural diamonds] are often four-fifths the age of the Earth. They’ve witnessed all this Earth history. They’ve sat in the deepest parts of the Earth undergoing huge pressure and then blasted to the Earth’s surface, where they’re sitting on your finger looking very nice.

- “The cool thing about big diamonds is that you can immediately see why people refer to them as ‘ice.’ Sure, ice, like diamonds, is a crystalline form and it glitters, but that’s not why. It’s really a reference to the fact that diamonds are extremely efficient thermal conductors. They suck all the heat out of your hand and feel really cold. That’s one way of telling a natural diamond from something like cubic zirconia, but you’ve got to have a pretty large stone to really be able to feel this, maybe two or three carats. The stone that really brought this home to me was 600 carats and the size of a baseball at a De Beers sorting house in Kimberley, South Africa. Then you really feel the effect.

- “Canadian diamonds occur in some of the most remote diamond mines on the planet, but they also have some of the most abundant diamonds anywhere. We usually talk about the richness of a diamond deposit in terms of its grade. In South African mines, that is between one and 50 carats per hundred tonnes. In the Northwest Territories the deposits can be hundreds of carats per hundred tonnes. So that’s well over a hundred, if not a thousand times richer than historically mined deposits. But the more remote a mineral deposit is, the more expensive it is to mine.

- “At the Earth’s surface, a diamond is a completely unstable material. Its stable form is graphite. But 150 kilometres down in the Earth, there is so much pressure that the structure shrinks. That shrinkage causes what is a really dull, unattractive material to turn itself into an extremely hard, bright, crystalline diamond. That means that, theoretically, diamonds are not forever. Every diamond on Earth is wanting to turn itself into a piece of pencil lead.”