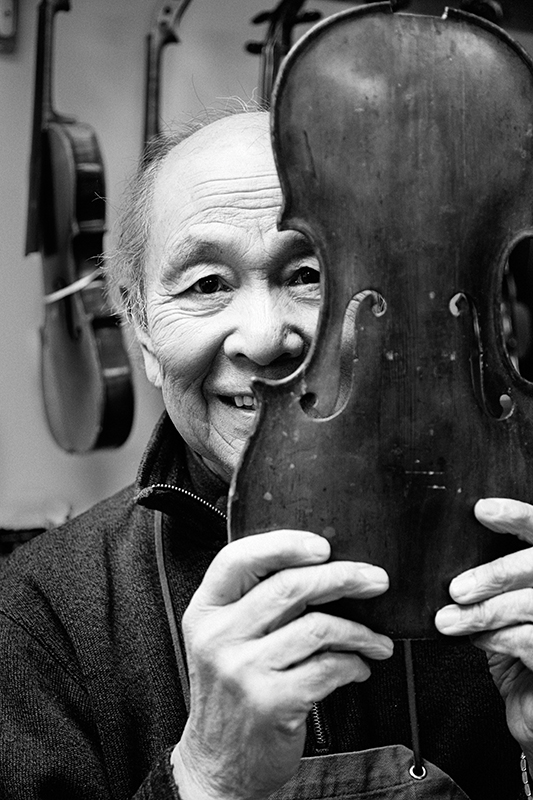

Who: PJ (Puay Jeng) Tan

Age: 80

Job: Violin restoration and repair

Experience: Stripped of its strings, a cello sits in the corner of PJ Tan’s violin repair shop, its bare fretboard and gentle curves giving the impression of nudity. Meanwhile, Tan recounts the decades he’s devoted to string instruments, especially the violin. He discovered the violin in Singapore as a child, and began learning to play in England in the 1960s. It was there he met with an accident – rather, his thumb met a cleaver – and, while it made professionally playing the violin impossible, it did little to sever Tan’s love for the instrument. Tan took up collecting, but his growing collection required repairs, which were often as costly as a new violin. Tan devoted the next 15 years to learning violin construction in North Wales, allowing his collection to continue to grow. He’s since sold a restored violin for $125,000 and seen a violin half a millenium old. In 1993,Tan came to Edmonton and opened up a repair shop upon hearing that the city produces extremely talented violin players.

- “It typically takes between 150 to 200 hours to make a violin. The top is typically made of spruce with a tight grain, and the back must always be maple. The wood should be air dried for a minimum of 10 years. You can put it in a storehouse, but they can’t be put in a box and sealed. They need to be stacked criss-cross, so the air can circulate through them. It will still dry if you don’t do this, but somehow it becomes lifeless, like a skeleton without flesh. The resonance diminishes.

- “The violin was originally an Arabian instrument called a rebec. It travelled down to Italy where Maggini started modifying it. Then it travelled to Cremona [in northern Italy] , and the Amati family started to build what would be known as the violin. From there, Stradivarius modified the shape slightly, and it became the violin as it’s known today.

- “The oldest violin I’ve seen was from the late 1500s. It was one by Maggini. This violin can’t be used anymore. In terms of playability, a violin can likely live up to 350 years. You’ll still see Magginis occasionally, but when you play them, they won’t give the same resonance; the wood is tired. It doesn’t have brilliancy when it gets older.

- “Every violinist’s dream is to have an Italian violin and a French bow. Somehow, Italian-made violins have a tone that’s one in a dozen. Two bows can be made of the same material, but those made in France … if you pull it across the strings, it will sound different. I suppose it’s like describing two women: You say the first is beautiful, and the next one is plain, but they both have a pair of eyes, and the same mouth. There’s something abstract about it that no one can actually interpret.

- “The hair [for bows] that was commonly used was horsehair from Mongolia. It doesn’t break easily, but it’s elastic as well. This is because it’s very hot during the day and very cold at night. It has an effect like tempering a piece of steel.

- “Some countries have horses that they keep just to harvest their hair. In [the former] Czechoslovakia they had horsehair that’s very white, and very expensive. The cost to rehair one bow with this hair costs about $300. Just for 110 strands. That works out to almost three dollars a hair.

- “When I came here, someone told me Edmonton is the violin capital of Canada. And if you look at it, the youngsters when I came here [in 1993] are now concertmasters of the Symphony Orchestra of Montreal [Andrew Wan, Concertmaster] , the National Arts Centre Orchestra [Jessica Linnebach, Associate Concertmaster] , and the Philadelphia Orchestra [Juliette Kang, First Associate Concertmaster] . In Vienna we have David Eggert – he plays cello all over Europe – we have another cellist playing all over Switzerland, violists playing in Frankfurt and Spain. They’re spread out all over the place.”