*A previous version of this story ran in Eighteen Bridges in 2013. It has been updated with new research by the author and the producers of Eddy’s Kingdom. The critically acclaimed documentary premieres locally Nov. 10 at the Metro Cinema during NorthwestFest. Tickets are limited to 100. For COVID-19 protocols, visit northwestfest.ca.

We arrived by train to a fur-trading post and, together with tourists in tees and shorts, walked an S-shaped dirt road in Fort Edmonton Park through a century of local history. Fanning themselves with the museum map, visitors stopped in mock antique buildings, where they encountered actors playing Hudson Bay trader John Rowand, premier Alexander Rutherford, and other historical figures.

As we strolled, not a single person took notice of the living legend at my side, Eddy Haymour.

He was familiar with the park’s landmarks. The living museum more closely resembled the modest city to which he immigrated, in 1955, not the sprawling urban landscape it has become. He pointed to a replica hotel — that’s where he applied for his first job in Canada — and then led me into the reproduced Capital Theatre — that’s where he’d watched his first movie on the big screen (Island in the Sun).

Eddy has tried in earnest to get a movie made about him. (That’s how we first met, in 2007, just as I was transitioning from the film industry to journalism.) Should his dream be realized, he hoped it wouldn’t resemble anything like the brash, 4-D sensory experience of the museum theatre.

Haymour emerged into the daylight, looking slightly disoriented as he led me across the railway to the original Al-Rasheed Masjid, Canada’s first purpose-built mosque, since relocated from 111th Avenue to the museum for preservation.

“See this space,” he said, pointing to a grassy lot between two spruce trees. “That’s the barber shop. The tour guide could tell them the history of the mosque and that I was married in there — but that I was a modern Muslim. And then would come the story of the barber shop, where they’d learn more about me.

A concerned look came over his face as he patted his pockets. He’d lost his glasses.

On the way back to the theatre to find them, he elaborated on his plan to build a replica of the 4 Haymours, his barbershop that became a destination for Edmonton’s elite in the 1960s. If his plan came to be, he told me, then the park’s 200,000 annual visitors could learn about, and from, his humble immigrant journey that took him from the fields of Lebanon to the ballrooms of Canada, from being a timid barber to a business mogul. He dreams about getting it built in his lifetime; he wants a few years to do the storytelling himself. Haymour tells his life story best in his hushed, campfire voice. I’ve heard it many times. It used to pour from his mouth rich as Turkish coffee, but lately it peters out, falters, gets lost in cul-de-sacs of memory as plain English words disintegrate before him.

His monuments and achievements have mostly been forgotten, and so too has the maverick. He is desperate to see a snappy twenty-something actor re-creating the Haymour story, bolstering the Haymour legend. Instead, all he can see for the moment, reflected back from the window of an old theatre, is the sagging face of an 83-year-old man in a white windbreaker, squinting under his bony, spotted hand.

Haymour turned around, blushing as he reached into his jacket and retrieved black, horn-rimmed glasses. They hadn’t left his pocket. Later, at the park’s diner, he put them on as he showed me his proposal to the Fort Edmonton Park committee. The letterhead read: “Heaven Before I Die.”

In the underground parking lot of the Canadian Embassy in Beirut, on February 23, 1976, Eddy Haymour, pointing with his AK-47, directed two of his cousins to the third floor, another cousin to halt the elevator and another to follow him up to the second level. Haymour sprinted up the stairwell, charged through the steel doors and pointed his weapon at the first person he saw: A senior citizen, presumably waiting for visa documents. “Stand up, put your hands behind your back and put your face to the wall,” Haymour said, according to his own recollection.

The man remained seated, dumbfounded, until Haymour repeated himself in Arabic. The old man dropped to the floor, begging for God’s mercy.

When the embassy staff and clients arrived to investigate they found assault rifles pointed at them. One trade commissioner had met with the lead gunman — Haymour — several times over the past four months to help him sell construction materials on behalf of a Canadian manufacturer. Or at least that’s what Haymour had told him.

“Is this a joke?” asked the commissioner.

Haymour rocked him in the shoulder with the butt of the rifle. After picking himself up, the commissioner, along with 20 diplomats, staffers and stunned Canadian visitors, were hurriedly led to the building lobby down a stairwell. Haymour’s collaborators had captives of their own. There were, according to varying reports, as many as 33 hostages in all. But the one person Haymour was looking for — chargé d’affaires Alan William Sullivan, Canada’s ambassador to the Arab region, only seven weeks on the job — was not among them.

“Where’s Sullivan?” Haymour asked the hostages.

“He’s not here,” replied an assistant.

“Bullshit!” yelled Haymour. “I saw him from my apartment.”

What the diplomatic staff were learning was that the wealthy Canadian businessman they’d been helping for months was a con man. They’d later learn that he’d spent most of the last two years behind bars and padded doors, and the past six weeks stalking chargé d’affaires Alan William Sullivan from an apartment across the street.

Haymour knew there was only one place Sullivan could be hiding.

According to Haymour’s version of events, he found Sullivan hiding under his office desk and enticed him out with an unloaded gun. None of the weapons had live bullets, he has assured me and every audience since. But Sullivan says that he was enticed out of his office another way — a bullet tearing through his door. (The retired ambassador allegedly still keeps the bullet in a container at home, all these years later.) Whichever way he was extracted, Sullivan soon joined the hostages in the lobby.

“If anyone has a weapon, throw it down, otherwise you’ll be wiped out.” No weapons were produced.

Haymour lowered his gun, then turned to Sullivan. He softened his tone. “I didn’t come here to hurt you, because if any of you get hurt I’ll be the first to lose. I came to ask for your help.” He paused. “Here’s my story.”

I’ve heard Haymour re-tell his story countless times since 2007. It usually begins with this: Three thousand years ago, in Yemen, the Haymour Dynasty ruled the desert with 35 successive kings and queens. Try as I might, I’ve never successfully located this dynasty in my research, only the Himyarite Kingdom, or Homerite Kingdom, of 2,000 years ago, which ruled ancient Yemen for six centuries and 46 successive kings.

The essence of truth is story, not facts, to Haymour, so he has stuck to this alternative ancient history, embedded himself in this narrative, and filtered his life story through his imagined bloodline.

It’s with this self-regard that 25-years-old Haymour successfully believed he could leave Lebanon nearly penniless to find his fortune overseas; that he could enter a business knowing only two English words (“Me barber”) and get a job; that he could train women to cut men’s hair at a time when they weren’t even allowed in the same bars; that he could found one of Alberta’s first colleges to train dozens more.

Decades later, a psychiatrist would tell a court that Haymour “suffered from a delusional state.” But what is so delusional about a man who achieves his dreams? And where is the suffering?

In 1960, only five years after immigrating to Canada, Haymour was granted citizenship. To celebrate, he threw a lavish party with Middle Eastern fare, belly dancers and 250 of Edmonton’s brightest lights, including two city mayors, Lieutenant Governor J. Percy Page and Alberta Health Minister J. Donovan Ross. “That was the best day of my life,” Haymour has said, without fail, in every version of the tale ever told.

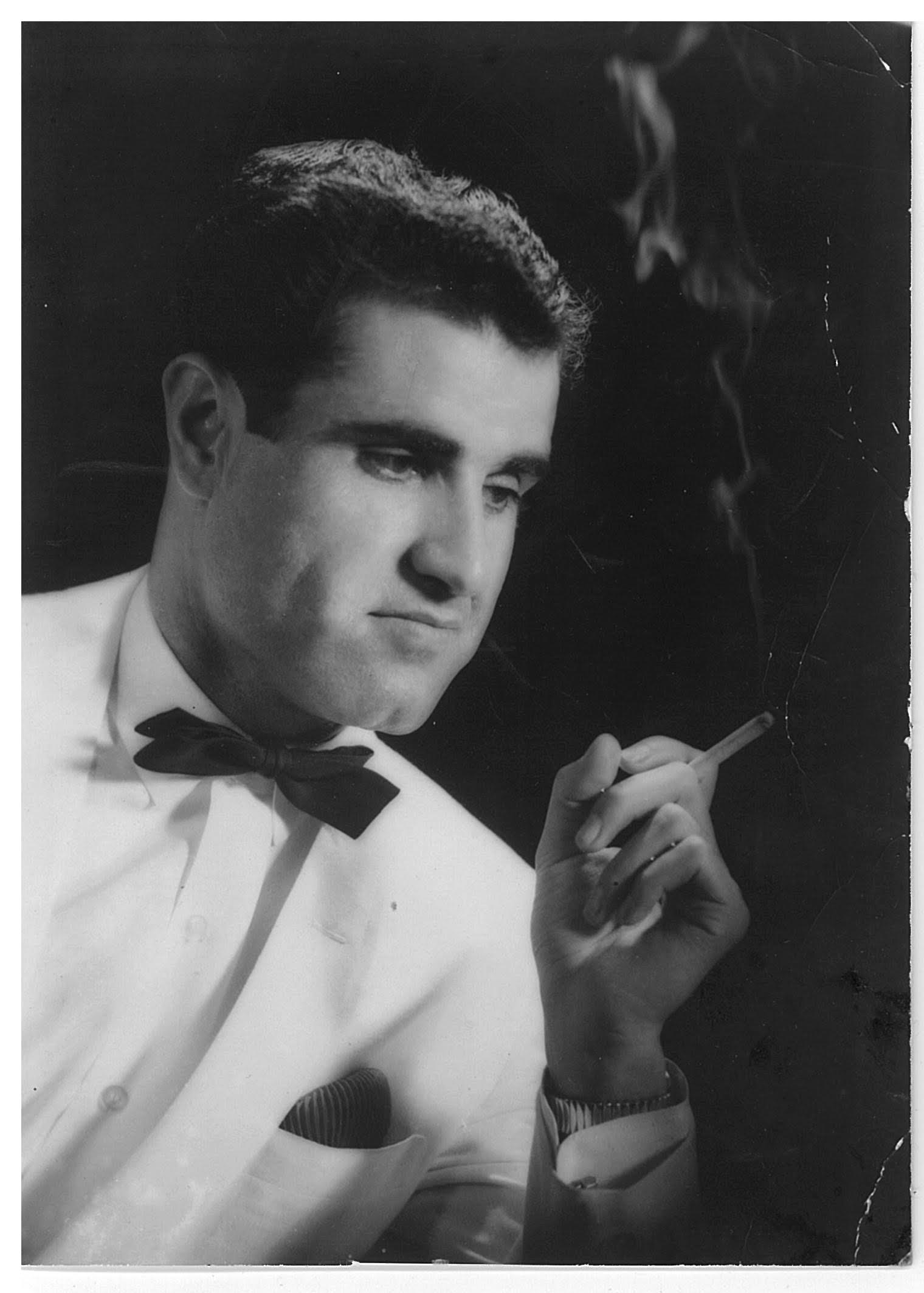

That night, he wore a white tux and bow-tie and, as he sat with his new wife Loreen, a 19-year-old farm girl, the provincial secretary toasted him: “I can assure Eddy that he will never be disappointed with Canada.”

The Okanagan town of Peachland, with its retirement homes and 30-kilometres-per-hour speed limits, was an unlikely place for the once fast-talking entrepreneur to plan his next venture, in 1971. He showed up at town hall in what one councillor described as a “zoot suit” to relate his vision for his newest property, Rattlesnake Island, three km off the Peachland coast in Okanagan Lake.

Haymour and Loreen, having survived years of marital problems and hoping for a fresh start, moved with their four kids. Eddy, searching for a landmark development project, found a private newspaper listing for the five-acre island separated from Okanagan Mountain Provincial Park by a narrow strait. At $10,000, it wasn’t exactly a bargain for a nearly useless landmass. It looked like the mountain’s severed, misshapen digit, where little grew but for a few lopsided pine trees.

The island was known less for what lived upon it than underneath it — the mythical serpent Ogopogo, Lake Okanagan’s version of the Loch Ness Monster, which the Sylix people of Westbank First Nations believed dwelled in a cave below the island. But when Haymour looked at the island he saw an opportunity to create his own folklore.

“I had a vision to do something good for the country,” he told me, recalling his plan for the Moroccan Shadou Theme Park. As he described it to the town councillors decades prior, the theme park would bring together both ends of his heritage, Arabian and Canadian, and embrace the multicultural spirit Pierre Trudeau had championed. Picture a mini-golf course, partly on the water, partly on the rocks, that would wind through miniature Great Pyramids; a storyteller every 20 feet (some on donkey, some making bread, some charming snakes); and his favourite, a concrete camel, “thirty-six feet tall by twenty-six feet wide, with steps to go into his stomach and thirty-nine flavours of ice cream inside.”

The first phase alone of Moroccan Shadou was budgeted for $300,000. But money wasn’t the problem, at least not at first. Though he had many supporters, including Peachland’s mayor, others balked at the project and protested to newspapers and councillors. Concerns ranged from disrupting the peace to an unseemly barge Haymour had made out of tires. The biggest concerns were raised by Desmond Loan, a town councillor, teacher and conservationist who believed the Lebanese immigrant’s dream would desecrate the island.

It didn’t matter to Loan that Haymour bought the land privately. Few even knew, or cared, that it was not public land. Loan and other locals had designated it a picnic site, but Haymour’s plan, he told journalists, would turn it into “Coney Island.” As Don Wilson, a volunteer museum curator, put it, “Des was strongly opposed to the developments on Rattlesnake Island and I believe he disliked Eddy until he passed away.”

Loan, however, isn’t dead. He’s well into his later years and resides in an assisted living centre in the area. (Editor’s note: Loan was alive when this story was first written in 2013. He passed away in 2014.) His daughter, Daphne Flanagan, agreed to meet me at a local café. Tears came over her as she reminisced about the once-immaculate Okanagan Valley, now handed over to developers for strip malls and urban sprawl.

“My father had very high values. He thought there should be a gate on either side of the valley, that it should be a national park.” Eddy Haymour, to her father, to her, was part of the problem. “He just wanted to come and make a fast buck, and had no concern for how he was leaving the land.”

Naturally, that’s not quite how Haymour remembers it. His engineer told him the development was structurally and environmentally sound, but no matter how prudent his plan, locals protested about the disruption and worried that sewage disposal would pollute the district’s water supply. Unconvinced by the engineer’s report, Loan voiced his concerns in a letter to his brother-in-law, then-British Columbia Health Minister Ray Loffmark, who passed concerns to the provincial chief medical officer, who spread the message to no fewer than four other departments as well as the office of then-premier W.A.C. Bennett.

The provincial riding of Okanagan-Similkameen, which encompassed both Peachland and Rattlesnake Island, happened to be the Premier’s riding, a fact that only heightened the medical officer’s negative reaction. In his internal memo, he suggested they “could Scotch it by exprop[riation].”

There was never a moment’s hesitation from the provincial government that they were going to put a halt to Haymour’s development, though today their rationale is hard to objectively identify. Some argue the government was driven by legitimate environmental concerns, others that it was political, and still others that it was purely xenophobia heightened by Arab-Israeli wars and the looming OPEC crisis.

Whatever the cause, provincial bureaucrats embarked on a campaign to grind Haymour down with endless and, at times, fake red tape. At one point, Municipal Affairs tried to stop Haymour by sending him a telegram informing him of an amendment to the Pollution Act clearly drafted to thwart him, but which hadn’t even been passed at that point. It was intimidation, plain and simple. Many years later, as the legalities were being played out, a 1986 Supreme Court file would note that, “the sending of such a telegram in advance of a regulation being enacted was highly unusual … Haymour was justified in ignoring it.” In fact, that file stated, “the government was caught in an embarrassing situation.”

In an effort to shrink government, the Social Credit party had recently handed the creation and definition of new zoning laws to the districts but this transition had stalled due to local bureaucratic inefficiencies. Basically, no one had gotten around to it—not even in the Premier’s own riding. Because Haymour hadn’t stopped building for more than ninety days at a time, he could do with the land as he pleased: build a house, open a barbershop, construct a wall. But every time he closed his eyes and pictured the island he saw pyramids and a giant cement camel.

“They took me to court three times and lost three times,” Haymour recalled.

Haymour persevered, but after two years the struggle began to exhaust both his finances and his marriage. He had been so focused on his dream that he neglected his family. Loreen took the children, including the newest addition to the family, baby Troy, back to Alberta. “My lawyer said, ‘Eddy, I can win any case but the problem is you don’t have any money left. My advice is go to Victoria and kiss their ass, ask them to buy the island, and go back to Edmonton.’” He followed that advice, but was offered a paltry $40,000, a fraction of what he’d already sunk into the island. He rejected the offer and doubled-down.

He organized a press conference for a single journalist from the Kelowna Capital News and theatrically blew out a birthday cake for his now estranged children. According to the reporter’s account, Haymour said “if he were not allowed to proceed with his development, he would drink human blood and eat human flesh to mark a black day for Canada.”

It was obvious to those around him that his mental health was eroding. In two years he’d gone from a wealthy, respectable father to a lonely man with a barren island, the justifications for which seeming opaque and conspiratorial. He continued his Sisyphean effort but it became less about his dream and more about revenge. The violence that had infected his thoughts would shock what few supporters he had left, but it wasn’t a surprise to his estranged wife, Loreen Janzen.

Decades after their divorce, the hostage taking and shortly after 9/11, Janzen penned her side of their story in a self-published book she titled Married to a Terrorist.

Janzen now lives in Calder Lake, about three hours north of Edmonton. She declined to be interviewed for this article, leaving only her book to tell her version of events. It depicts Haymour as physically abusive, sex-crazed and swindling. The book is also woefully problematic, conflating as it does the whole Arab world into a single B-roll of honour killings, niqabs, fundamentalist Muslims and other negative stereotypes.

When read in tandem with Haymour’s 1992 self-published memoir, From Nuthouse to Castle, the reader is left with a classic he-said/she-said. According to their son, Lee Haymour, both books bend the truth. “You could say one is truer than the other, but as for the percentage?” he said, joking. His mother’s truth, he told me, is the lesser truth and her book is “more like her perception of how things were than the reality.”

However, there’s some credence in Janzen’s claims of abuse. Eddy Haymour maintains it happened only once at a “desperate” time, but Lee disputes his father. Lee recalled a few incidents of his father’s spousal abuse during his childhood, including one that led young Lee to call RCMP to intervene.

Lee also verified one of the most unsettling moments in Janzen’s memoir. During his parents’ first separation in the late 1960s, his father kidnapped the children under the pretense of a visit to the zoo, taking them on a plane to Lebanon. He left at a private boarding school while he travelled the Middle East. “It’s vivid,” he told me. Lee, who legally changed his name from Lebnan (“Lebanon” in Arabic), still struggles with trauma. “Taking care of my two little sisters—I mean, I was little—and my old man taking off, leaving us for in the middle of nowhere, no Mommy? It affected me.”

The reason for travel, Eddy Haymour later told me, was to establish a network of political connections in the Lebanese parliament, the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the Jordanian palace. Years later, after moving to B.C. and bureaucrats stymied his theme park, he began to put some of these contacts to use.

In 1973, Haymour announced to his one true confidant, his friend Ralph Schouten, that he was returning to the Middle East to drum up political support for his cause. Haymour told Schouten that he hoped to leverage letters of solidarity to shame the B.C. government into either letting him build his park or buying the island for his investment.

Haymour did, in fact, procure such letters from various Lebanese ministers, including a former prime minister, but that’s not what he told Schouten when he returned to the Okanagan six weeks later.

Haymour’s version of the events that followed runs like this: The morning he got back from the Middle East, Schouten dropped by unannounced, which caught Haymour by surprise, since he hadn’t told anyone he was home. His suspicions aroused, Haymour decided he wanted to test Schouten. He told Schouten he’d returned with “six letter bombs” and would need official RCMP detachment envelopes in which to send them (so as to give the packages an official air). Schouten agreed to try and get the envelopes, and came back later that morning with them in hand. The ease with which Schouten secured the envelopes made Haymour even more suspicious. He wondered how his confidant and friend had managed it so quickly. Later that day, Haymour went to Schouten’s house with the now-sealed RCMP envelopes and asked his friend to address and then send them to the Premier, to Des Loan, to his wife Loreen and to his other sworn enemies. Haymour says he did this to test Schouten’s loyalty, like Abraham on the mountain. Haymour left the envelopes on Schouten’s table and walked out of the house.

The police were waiting outside.

Schouten, it transpired, was an RCMP informant. He had befriended Haymour via the ruse that he was a vengeful airline attendant fired for pocketing money off ticket sales. Perhaps the persona was created to play into recent Palestinian hijackings. Whatever his character inspiration, it worked. Haymour had shared all his frustration and anger right till his arrest.

The RCMP had been following a trail of bizarre threats for months. According to a court file, Haymour — never a man to ignore the open arms of hyperbole and exaggeration — had told Schouten he was trying to obtain an M-14, one hundred thousand rounds of ammunition, Russian grenades, that he had contacted an explosives expert in Washington state and that he had several passports and ties to guerrillas. Now the RCMP thought they had hard evidence. They had letter bombs. But when they opened the letter bombs they found letters of political support from various Arab dignitaries.

Haymour had wrapped them in cloth to give them physical weight, he says, to prank the RCMP into thinking they were explosives. “I wanted to show them they were fools,” he told me. Haymour has consistently maintained this since his arrest. According to the court file, the improvised explosives, though “duds,” were “realistically resembled letter bombs.”

Thirty-seven charges ranging from unlawful possession of explosives to attempted wilful damage to property were laid against Haymour. But as his claims and threats were parsed out and revealed as either hyperbole or delusion (depending on whom you ask), so too were the charges reduced, to a single misdemeanour: Possession of two child-sized brass knuckles he bought in Lebanon and hoped to give Lee if he ever saw his kids again.

Haymour wanted to plead guilty, which would have led to a fine, but the Crown took the unusual act of forcing an insanity position, maintaining that Haymour so believed in his outlandish and violent claims that he was a danger to the people he’d threatened, particularly those in government. The judge ordered that Haymour be held without bail.

As the trial stretched on for seven months, he was moved between remand and various jails. He was allowed one trip to sign over the deed to Rattlesnake Island, selling it and its incomplete development to the government for a pittance. After he signed and put the pen back on the table, the handcuffs that had been briefly removed from his wrists were returned, and so was he, to his cell.

In jail, he cut other inmate’s hair and intently listened to their stories, while having to retell his own to psychiatrists sent to assess him. One doctor attributed most of his behaviour to a cultural background “that accepts violence as a way of life.” Four others, however, believed Haymour’s behaviour was attributable to paranoid schizophrenia and other psychoses. “My impression over all,” wrote Dr. R.L. Whitman, “was that he suffered from a delusional state which was systematized, specifically that he believed that he was being harassed by civil servants, and specifically this harassment arose out of the desire of Mr. Bennett to accumulate this property for himself or his children … [this is] not the kind of evidence that a normal person would accept.”

A decade later, it emerged that Haymour was being harassed by civil servants and the British Columbia government did conspire to expropriate his island. But in 1974, the psychiatrist’s report was just one piece of evidence used to label Haymour insane. On September 19 of that year he was sent to Riverview Hospital, a psychiatric institution in Port Coquitlam, where he would be kept in strict custody for an indefinite period.

Eddy Haymour was a barber, he was an immigrant developer, he was a bit of a hustler and now, simply because he had picked the wrong location to express his dream and because he possessed an overdeveloped sense of his own historical importance, he was placed in a notorious mental facility.

According to his memoir, Haymour passed the time at Riverview cutting hair and leading an arts and crafts club, where he built an elaborate miniature plywood and glue model of a high-density development. He told anyone who asked that it was a mock-up for a theme park on Rattlesnake Island. In the context of a mental hospital, his boundless imagination seemed to find a comfortable home, but he never stopped pursuing his release.

With the dogged assistance of Robert Gardner, a defence lawyer who represented other Riverview patients, Haymour secured his release after 12 months on a writ of habeas corpus, though he maintains that he and his lawyer quietly made a deal with the parole board that, if released, he’d leave the country.

When Haymour walked out of Riverview he took his elaborate mock-up with him. Just blocks from Riverview was a large construction firm called Synkoloid Metal Products. Posing as a Lebanese entrepreneur and showcasing his elaborate architectural model, Haymour ingratiated himself with George Clayton, Synkoloid’s president.

He hooked Clayton on the excitement of building this project overseas, showing Clayton the miniature office towers, the suspension bridges, the apartments, the attractions. He convinced Clayton that he’d be able to raise millions through his Middle Eastern connections. Clayton bought in and even considered opening an office in Beirut. Haymour now had his cover to operate in Lebanon. As Clayton later told Canadian Business magazine, “I guess you might say I was the victim of an elaborate con job.”

Five months later, as Haymour and his cousins were rounding up hostages in the Canadian consulate in Beirut, hundreds of spectators gathered around the embassy. It was located on Hamra Street, the capital city’s centre of commerce, liberalism and activism, and neutral territory in a nation entering the early days of a 15-year civil war. Lebanon had not yet truly combusted, but it was so inevitable that many at the time believed that Canada’s hostage crisis — that a man named Eddy — would be the spark.

the army and militants from competing Muslim and Christian factions surrounded the consulate with tanks and rocket launchers, each vying for control.

Inside, Haymour finished recounting his story to Alan Sullivan, who then opened a line to Ottawa. Haymour’s demand to speak with prime minister Trudeau was denied. The prime minister was busy deescalating a situation with Yasser Arafat of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, offering, or maybe threatening, to “rescue” the captives in exchange for diplomatic relations.

Trudeau instead authorized Sullivan to negotiate around Haymour’s other demands: his children sent back to Lebanon; an in-person apology from the psychiatrist who declared him insane; half a million dollars or his island back; and immunity.

Lee Haymour, who was 14 at the time, remembers overhearing his mother on the phone discussing his father’s demands with James Armstrong Richardson, the Canadian minister of defence. “We were scared,” he said. “We thought we were going to get traded and would have to go back there. I had no thoughts about what he was feeling or where he had been, what he was trying to do. We were just thinking, Are we going to get traded for hostages?” Ottawa has neither confirmed nor denied that it entertained this demand, but, according to Janzen’s book, the minister of defence told her a plane was awaiting her and the children.

Haymour surrendered after nine hours without so much a slap on the wrist. The Lebanese government fined him $210. Trudeau did not meet his demands, including immunity, since Canada did not have the legal any laws in place against embassy terrorism, but his government did give him a trial to defend his property and civil rights in court. Haymour returned to Canadian soil a free man.

Haymour currently lives in a Westmount neighbourhood seniors’ complex. The walls of his retirement suite are decorated with the architectural renderings of his would-be island park. A few months after our interview in Fort Edmonton Park, Haymour called me over one day to share important news, but wouldn’t elaborate over the phone. When I arrived, I remarked that he was now living quite close to his original barbershop from the 1950s, the 4 Haymours. “Closer to heaven,” he replied.

He placed a mug of coffee for me on the only empty spot of his kitchen table; the rest of the surface was under messy stacks of papers. His thin memoir sat atop blueprints of unrealized projects, including a bright and colourful personal mausoleum designed after ancient Yemeni architecture.

I sipped my coffee, unsure of what he’d dreamed up now that his barbershop proposal to Fort Edmonton Park was dead in the water. (A representative told me the board rejected the concept on the basis of the park’s master narrative timeline — 1865 to 1920 — not because it paid homage to a notorious hostage-taker.) Haymour had called me over to get my opinion on a biopic synopsis, which he hoped to get “in the right hands” with repeated calls to the Alberta Film Commission.

I listened as he yet again relayed his life story, burrowing ever deeper into his self-mythology: It was the story of Eddy Haymour, the man who left his country with $1 and arrived with $17 by cutting hair on ship; the man who made himself wealthy; the man who had a vision to bring people and cultures together at a new theme park; the man who fought the government and brought it to its knees.

A wealthier man would simply buy himself a place in time. He would finance the movie himself or maybe fund a university building in his name. Haymour could have been that man but now his only currency is his mythology, a currency that time is devaluing.

There is surprisingly little known about the siege of the embassy in Beirut. There seem to be few existing memos or transcripts, though at least twice in 1976 potential legal action against Haymour was tabled in the House of Commons.

Of course, whatever discussions took place behind the doors of Parliament in February of 1976, the outcome was radically different than the one we’d expect today in the era of radical Islamists, anti-Muslim populism and Quebec’s Bill 21 legislation against religious symbols. As former prime minister Stephen Harper has stated on numerous occasions: “Canada does not negotiate with terrorists.” There are laws in place now that would allow for and encourage putting someone like Haymour on trial in Canada for crimes committed outside the country — if he’d ever made it back to Canada, that is.

But the word terrorist was not commonly used when Haymour and his cousins attacked the embassy in the 1970s. Even when Haymour’s name appeared on the cover of the Globe and Mail, he and his accomplices were “gunmen” and their attack a “siege.”

Read with modern eyes, a person couldn’t be faulted for thinking of Haymour as a terrorist but most people in Peachland tolerated him and others even heralded him as a hero, as a man courageously standing up for his rights. The local historian Richard Smith, who like many in the area assumed Haymour was dead until I called and told him otherwise, told me that most residents had welcomed his return.

Nobody sympathized more than Pat Hay, an Okanagan banker whom Haymour courted and married soon after his return. (They have since divorced. Like Loreen Janzen, Hay declined to comment for this story.) Throughout the early 1980s, she helped drum up public and legal support for Haymour, who continued to battle the British Columbia government upon his return, arguing for more compensation or the right to pursue his project unchallenged. His case had been thrown out of a lower court, Haymour took it to the Supreme Court.

In 1985, CBC’s The Fifth Estate aired a documentary about Haymour, weaving a narrative about an ambitious immigrant who dared to dream only to be thwarted by the government and who was then forced to take justice into his own hands. The following year, in 1986, the Supreme Court ruled on Haymour’s case. It found that Haymour had indeed been wronged. “On the evidence before me, he was justified in having the [paranoid] belief he did,” Supreme Court Justice Gordon MacKinnon wrote. “To subject the plaintiff to that charade was, in my view, highly improper if not consciously cruel.”

The British Columbia government was ordered in three separate suits to pay Haymour damages for the island amounting to $400,000. The amount didn’t compensate him fully for what he’d invested, but the formal vindication from the highest court in the land was compensation beyond measure. After the judgment, Haymour, friends and family, including six-year-old daughter Fadwa, rafted over to Rattlesnake Island (which had, in the intervening years, been annexed as part of Okanagan Mountain Provincial Park exactly as his first nemesis, Desmond Loan, wanted).

A CBC crew was there to capture the jubilation as Haymour and his group of supporters danced beside the stone fire pit he’d constructed 15 years earlier. Haymour no longer owned the island and his theme park would never be built on that site but when the video footage of their celebration was rebroadcast to the nation, it was clear Eddy Haymour had won.

Or had he? How did he define victory, justice, and closure? Eddy Haymour was free and had been vindicated, but he had not finished writing the story he wanted to leave for his family. “I want to have an ending to Haymour,” he told me.

With some of the money from his settlement, he partnered with his nephew, a successful Kelowna businessman, and built the Castle Haymour Fantasy Inn on the outskirts of Peachland, directly across from Rattlesnake Island. The inn featured Arabian-themed bedrooms, 1–course Lebanese feasts, a belly dancer and, at every dinner, a storyteller: Eddy Haymour.

“If he was in the middle of the story, don’t even bother him,” his daughter Fadwa, who is closest to him, told me. Those were the best days for Fadwa, who had a princess-themed room in the Castle, though one thing never sat well with her — the statue of her grimacing father pointing across the lake to the island. “It was right underneath my bedroom balcony. I mean, I got the point of it but I hated it. It was so embarrassing and it was a complete, life-size replica.”

There was a period when it looked like her father’s myth-making might amount to something lasting. With CBC’s backing, Omni Film Productions of Vancouver took out an option on his life story in 1988, but Toronto screenwriter Paul Ledoux struggled to make him sympathetic to Western audiences. “There was a shift in what was going on in the world of terrorism,” Ledoux told me in a phone interview. “The [first Palestinian] intifada coloured the way people would look at it.” Omni released the option and a smaller American company picked it up. But it too eventually dropped the project.

Haymour’s story was dramatized in 1994 by Western Canada Theatre, in Kamloops. But with a small budget, a single stage and six actors, playwright John Lazarus had to find an elegant solution to convey this epic spanning two continents and three decades. The actors played actors workshopping a play about Haymour, with an additional character playing the subject who walks onto the set to fix the story his own way.

It took a new dimension when a third Eddy Haymour, the real one, arrived from Peachland to attend rehearsals and at least a few shows. “He’d sit in the front row … turn around and laugh with the audience,” recalled Lazarus. “He went up on stage at the curtain call and took a bow with the actors. I had the impression that he was taking a bow for his life, which I thought was peculiar. I sometimes had the feeling that he was obsessed with his story being told.”

The Trials of Eddy Haymour never got a second production. “I do think that there’s some truth to the idea that it’s hard to sell a sympathetic Lebanese Muslim man with AK-47s and hand grenades in the present climate,” Lazarus told me. “But I think it’s a great Canadian story.”

Haymour’s tale, and myth, steadily began to lose its lustre. So did the Castle Haymour Fantasy Inn. He sold his shares back to his nephew in 2003. By then, he and Pat Hay had separated, so Haymour returned to Edmonton, the city that made him, hoping for better luck. And, as our most recent meeting demonstrated, he is still hard at work trying to find someone to help him get the story of his life told.

“I put my heart into it,” Haymour said to me about the movie version of his story. “I never for one second think it’s not going to be made.”

In March 2013, I stayed three nights at the former Castle Haymour, which is now Peachland Castle. Pulling into the driveway, though, it was clear that the image on the cover of his book, From Nuthouse to Castle, was never fully realized. It was half the size, there was no grand skywalk and the mystical Arabian decor inside had been replaced with sparse, plain furniture.

It was off-season in the Okanagan and it transpired that the majority of the other “guests” in the hotel were recently released patients from a nearby hospital’s psychiatric ward. The hotel owners had forged a deal with the hospital to help get them on their feet. The title of Haymour’s book had been reversed and realized.

My fellow guests were completely unaware of the history of the building they inhabited but allowed me to indulge them after dinner that first night. Soon my audience, a labourer of retirement age and a 21-year-old woman who’d been homeless for much of her adolescence, were caught up in the story.

Both having been hospitalized for psychiatric treatment, they saw themselves in Haymour. Perhaps they felt his vindication and triumph more firmly; it was hard to say. When I was done, I gave the young woman a copy of Haymour’s memoir (which I’d found in the hotel). After three days, I could see that she still hadn’t touched it. Aside from the book, all other traces of Haymour have been erased from the site, including the statue.

I asked around Peachland, and although no one could tell me what had become of it, long-time town residents had not forgotten Haymour or his statue.

Haymour’s story still fascinates around Peachland, to a degree, but the legend is beginning to warp and weave. “I’ve heard rumours,” a woman at the local tourism information centre told me. “I heard they found cameras in the Castle. Well, not cameras, but peepholes.” (The current owner found no such thing during renovations.) At the Blind Angler restaurant, a waitress told me that Haymour “got put in jail for taking the Canadian consulate hostage in Iran.” Her co-worker knew the name: “the crazy guy who thought that he owned Rattlesnake Island?”

“It’s like the story around the campfire,” Don Wilson, the museum interpreter said to me. “You know, how when you tell it and it comes back to you it doesn’t bear any resemblance to the original story. It gets added to as it goes.” Even those who know Haymour best acknowledge how difficult it is to tell where reality ends and fantasy takes over. “Maybe a lot of people just don’t know how to put him in a history book,” his son, Lee, told me. “How do you? You’ve got a mix of Aladdin and Bin Laden — how do you write that down? And what’s true and what’s not?”

On my last day in Peachland, I set out for Rattlesnake Island in a rented boat with John Tooners, a local guide who frequently takes visitors across the lake on wine tours while relaying tales of the Ogopogo lake monster. As Tooners steered us closer to the island, it appeared smaller and smaller. Even from the boat, I could see that most of what stood on the island was wrecked or disposed of.

I climbed out and onto the rocks where the dock, along with the pyramid, had been long ago shattered and removed by environmentalists. Chunks of cement remained, broken in half, with rebar sprouting like steel weeds. I could easily make out the nine-hole mini-golf course, which was fractured by mounting earth, the cups so full of grass a golf ball wouldn’t fall in. A graffiti artist had bombed the enormous brick barbecue pit with the tag “4Get.” As I walked around the island, a kind of sadness came over me. This had been a man’s dream, conceived and constructed to represent and celebrate his life, his myth, his people, his ancestry. And now it was vanishing.

I returned to the boat and stepped back in. I asked Tooners if he ever told tourists about the man who went to jail and a mental hospital and who held an embassy hostage over the rights to this island? “Oh yes,” he said brightly. “People love it.”

I thought this would please Eddy Haymour, this small sign that others also believed in the power of his story. As we puttered back across the lake, I asked Tooners to tell me the tale. It was a brief and not particularly magical telling. We neared shore as he finished. “And that,” he said, turning off the boat engine, “is the story of Mr. Haley.”

Eddy Haymour has always been in search of a legacy to his liking. My story was not it.

Shortly after it was published, he presented me with an annotated photocopy of the article that first ran in Eighteen Bridges. Haymour had a few legitimate grievances (two small inaccuracies corrected for this version), but he was mainly upset that I did not tell his story well enough.

I omitted the “fact” that his weapons were unloaded and did not parrot Haymour’s insistence that he could not “hurt a fly.” Most disappointing to Haymour, I’d included his ex-wife Loreen Janzen’s allegations of abuse and his son Lee’s corroboration. He believed I should have asserted his apparent justification that he’d caught Janzen in an affair.

Setting aside that Janzen denied infidelity, I argued with Haymour that his motive was irrelevant. Haymour argued back, and that’s more or less how our subsequent conversations continued until I stopped answering his calls.

We didn’t talk for years until bumping into each other at a Kelowna film studio, where we were shooting interviews for Eddy’s Kingdom, a biographical documentary released this year to critical acclaim. Our exchange was brief and awkward, and before long Haymour was again disputing my version of his events.

Is my version the correct one? Is filmmaker Greg Crompton’s take in Eddy’s Kingdom?

The film uncovered testimonies to his violence that stunned even me. Other scenes, such as Haymour’s current efforts to apparently get Rattlesnake Island back, struck me as performed. (He’d never once expressed to me any desire to repossess the island in a decade of conversations.) However, the film’s most dramatic revelation was something I’d heard many times from Haymour himself and Haymour only: he claims that he initially plotted to bomb the B.C. legislature before the hostage crisis, and went as far as stalking the building to draw up his plans.

He remains the lone narrator of this event, which he reenacted for filmmakers on the grounds of the building. I chose not to include these claims in my story, and would not have included them in the documentary either. But such is the nature of storytelling. Crompton’s interpretation is neither mine nor Haymour’s, and neither of the three will perfectly match future interpretations.

The most recent version was told by comedians Bobcat Goldthwait, Dave Anthony and Gareth Reynolds on the comic history podcast, The Dollop. If Haymour has heard it, he’s probably more approving of his story being told to a wide audience than disapproving of the way it was told.