Class of 2011 When did minor sports become so stressful? There are road trips on the weekends. Hotel stays. Practices at 5 p.m. on weekdays. The family dinner becomes a thing of the past. And the costs, even for sports outside of hockey, can go well into the four digits, even before you factor in the cost of gas. There are the times parents have to politely ask their bosses if they can leave early so they can take their kids to games. There’s the stress of being stuck on the Whitemud, but your kid has to be across town for a 6 p.m. kickoff.

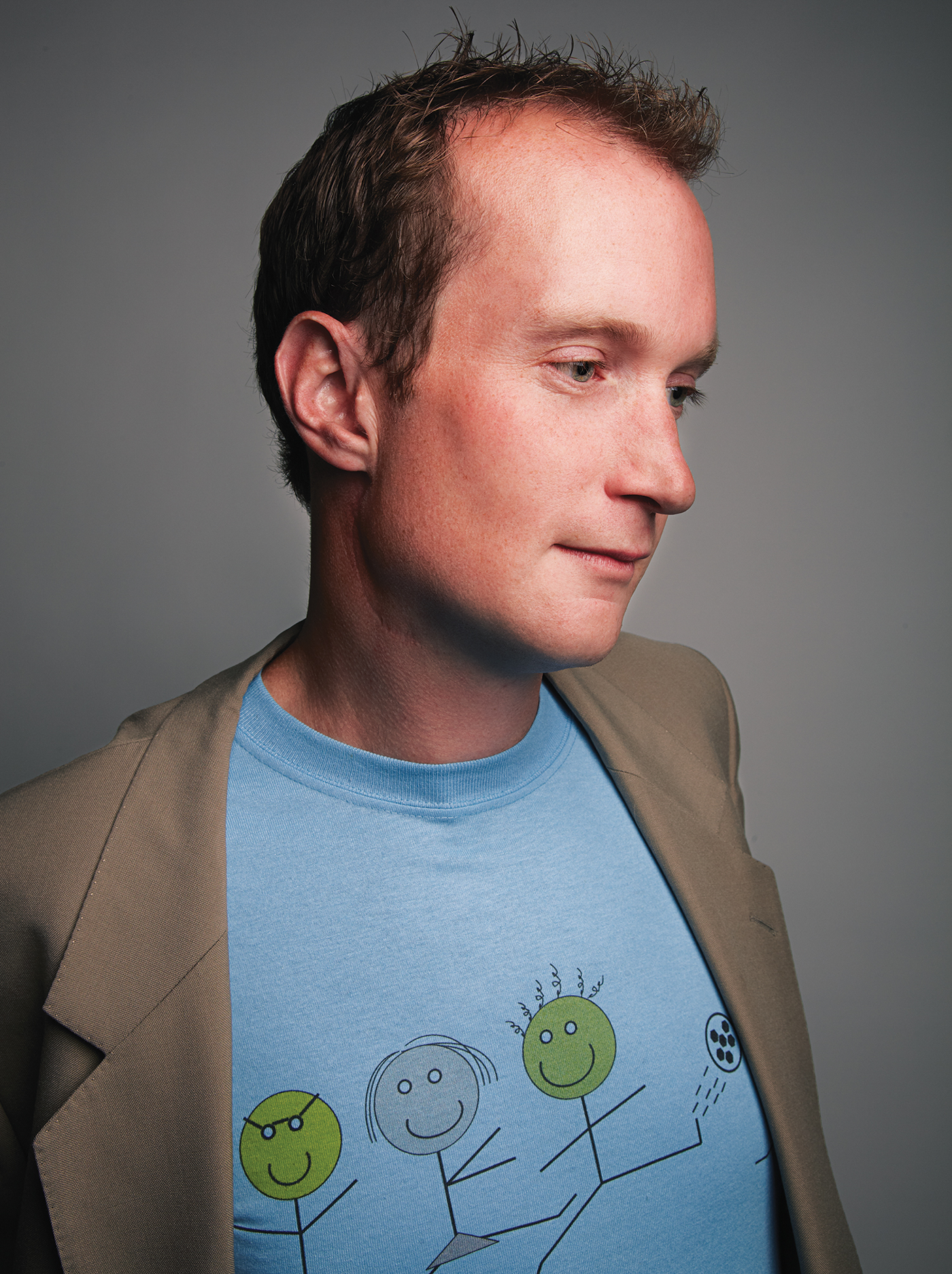

Tim Adams has had enough. He believes that not only do kids need a less stressful environment in which to play, but that families need their lives back, too.

In 2011, while still working at CBC Radio, Adams was named to the Top 40 Under 40 thanks to Free Footie, the organization he created to give under-privileged kids the opportunities to play soccer.

Now, it has grown into a full-time passion. Adams has left CBC to focus on Free Footie. Kids from 16 “anchor schools” are picked up when classes end and travel by bus to various rec centres and soccer venues in the city. They play soccer, basketball, street hockey, some touch football and rugby. More schools come online in the spring months.

The idea is that, no matter how rich or poor, kids should be involved in sports after school, not after supper. If sports become an end-of-school-day activity, Adams believes it would free up times on weeknights and weekends for families to be together. He believes the days of parents needing to burn vacation time so they can take the kids to tournaments have to end.

“We are still basing minor sports on a model from 80 years ago,” says Adams. “Things don’t work like that anymore.”

Parents who have to work weekends are often shut out from being able to place their kids in high-level sports. Some can’t afford the ever-rising fees.

“The major barrier is the time of day,” says Adams. And that doesn’t matter if the parent makes $25,000 or $250,000. We need to make sport an after-school activity. We need to flip the script.”

It gets so bad that Adams says many parents have told them they’re happy when “rain days” force games to be postponed, just so they can have a quiet night at home rather than scrambling to get kids to their activities.

Adams says that, while the program focuses on kids from Grades 1-6, those in Grades 7-9 can go into referee-training programs, and those in Grades 10-12 can go into coaching. He hopes, as kids get older, that they learn more about the careers available in sports, from officiating to administration.

“One of my ultimate goals is that, one day, one of these kids is going to take my job away from me,” he says. — Steven Sandor

Class of 2017 MS’ed With The Wrong Girl. The filmmakers hit the nail on the head with a name for this documentary. Nothing sums up Patrycia Rzechowka’s story better.

Her resilience in dealing with the autoimmune disease and her incredible ability to inspire others have become a driving force behind the documentary.

Two years ago, Rzechowka earned a spot on Top 40 Under 40 list.

Since then, she’s been featured in a film, continued to raise thousands of dollars through an MS bike fundraiser, and hasn’t stopped her efforts to support others who live with Multiple Sclerosis. Between her advocacy and event planning with MS Society, it’s no wonder people often assume that Rzechowka works for the nonprofit.

In 2018, she also became the face of an Edmonton-made short film, MS’ed With The Wrong Girl: A Fighter’s Story, filmed by Kelly Wolfert. Rzechowka admits it was a challenge to let people see the most vulnerable parts of her life — but it’s worth it. “I keep a lot of my struggles to myself — I don’t like to worry people,” Rzechowka says. “But I feel like I’m helping and reaching more people by putting myself out there.”

Rzechowka hopes the documentary can give viewers something to which they can relate, regardless of condition.

“When people don’t really understand your struggles, it makes it even worse,” Rzechowka says. “It’s nice when people care enough to ask questions.”

Her goal now is to work with legislation and policy, which she’s been doing for the past year, as a part of the team that’s reviewing the Police Act, a role that’s required her to temporarily step away from her role as Provincial Public Complaint Director with Government of Alberta.

Before being diagnosed with MS in 2012, Rzechowka’s dream was to become a police officer.

With her career hanging in the balance after diagnosis, she did one thing that made sense to her at the time — signed up for the MS Bike Ride. And she hasn’t stopped riding since then — over the years, she’s raised over $100,000 through the event. — Kateryna Didukh

Class of 2009 Christy Morin remembers when she decided to stay. She will always remember when, because it was one of the scariest of her family’s life. The 2009 Top 40 alumna was living in the house she and her husband bought in the Alberta Avenue neighbourhood, with plans to eventually flip it and move somewhere else. Plans changed when her husband met the new neighbour.

“We had gangbangers next door, and the owner just continued renting to the same group of people,” she explains. “One night, my husband, Darcy, had gone out to get a package from the van. And one of the gangbangers came up to him and said, ‘If you call the five-o again, there will be retribution. When your wife comes home from work, or your kids are in the backyard, we’ll just throw a pit bull over the fence and your kids’ faces will never be the same.’ I stood at the screen door listening. It was a moment where time stood still.”

Of all the reasonable reactions to an explicit threat, Darcy went with the unexpected: He put his arm around the neighbour and said all he wants is to live in peace and happiness with his family. In a moment, Morin was convinced to stay. “I just thought, if we move, who’s going to help this neighbourhood?”

That was in 2005. By 2007, Morin, along with neighbourhood artists, incorporated the Arts on the Ave Edmonton Society, based out of The Carrot Community Arts Coffeehouse. The society’s goal is to better the area by “cultivating artistic fellowship through arts celebrations, signature art festivals and tradition,” and “create opportunities for all individuals to experience the joy of artistic expression.”

Together, they started Won’t You Be My Eastwood Neighbour — free parties in the back alleys of particularly isolated people. “We found out that lack of food security was huge, and many didn’t have furniture in their apartments,” Morin says. “I asked one of the sergeants afterwards why they picked those spots, and he said, ‘Because we believe this initiative would have the greatest impact in those areas.’”

Local businesses also play a role, and many agreed to install behind-the-counter monitors that display CrimeStoppers profiles of suspects in between community ads. It took just over a month for someone to identify and help catch the first suspect. “We not only want to reduce crime, but also help to create strong and caring communities,” says officer Ashley Hayward. “We believe local businesses and organizations like Arts on the Ave can have a leading role in the process.”

Morin’s optimism is infectious, but she’s earnest and honest about how far things have come. The community still has problems, but the average number of criminal incidents is down since 2009 and, with over a dozen area festivals popping up in the last decade, including SkirtsAfire, Deep Freeze Festival and Thousand Faces Festival — all separate from but inspired by Arts on the Ave’s Kaleido Festival — the progress is undeniable. “

Kaleido means the coming together of colours and shapes, only to be seen through the presence of light, and I think that’s what’s happening here,” Morin says. “Everyone always asks: Have we tipped yet? I don’t think so. But it’s a movement. And no one person can stop a movement.” — Cory Schachtel

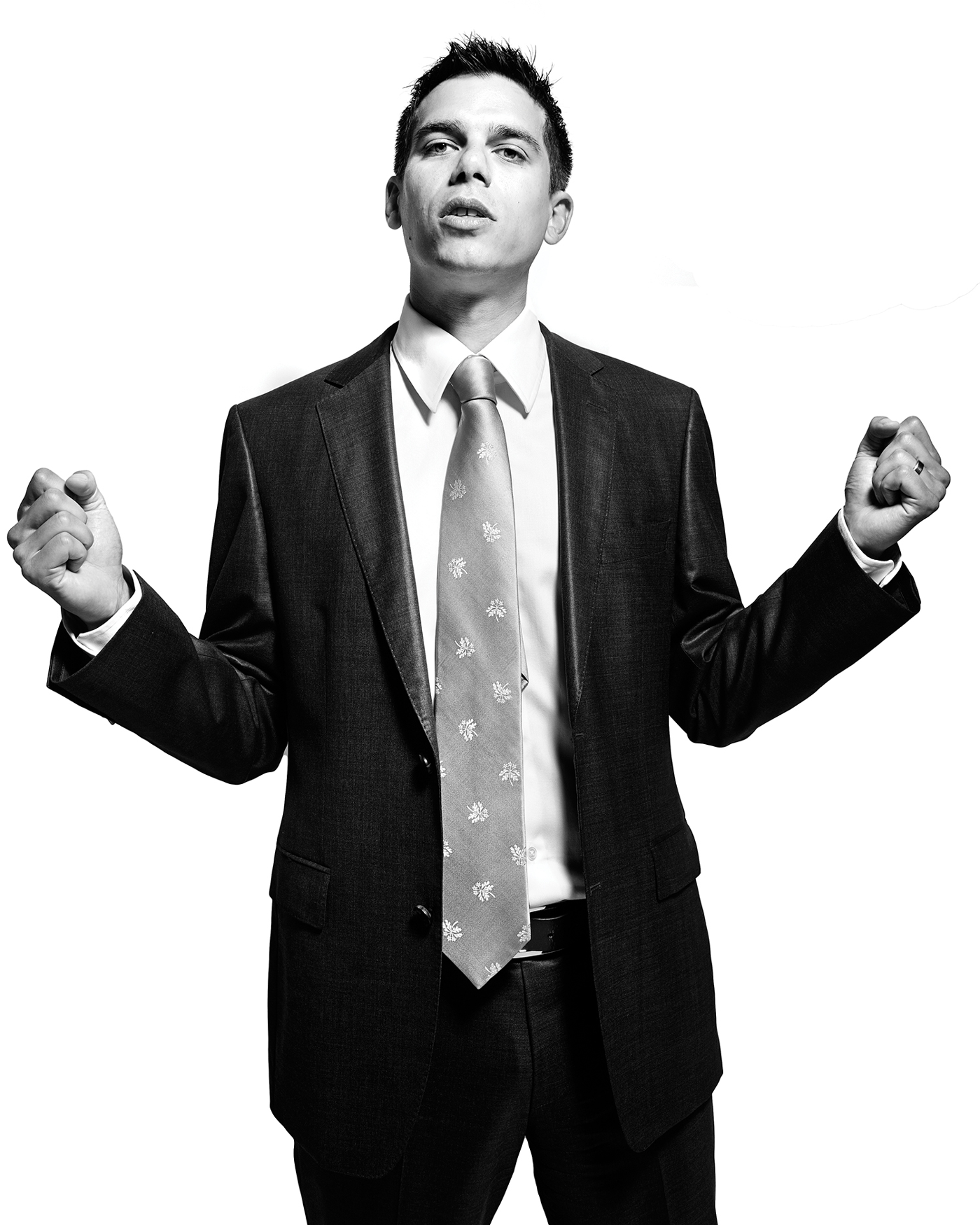

Class of 2011 Take a look back at the 2011 edition of the Top 40 Under 40, and the photo of Erick Ambtman shows a man looking defiant. He has both his fists pumped, ready to take on the world.

Looking back, Ambtman has a confession to make. He was in over his head. He had just taken the job as the executive director for the Edmonton Mennonite Centre for Newcomers, an organization that was in danger of going broke. It was overextended.

“The reason I got the job was that no one wanted the job,” says Ambtman. “But I was young and naïve and willing to work.”

Now, the scope of the organization has tripled since Ambtman took the job. The centre serves between 18,000-22,000 newcomers a year. A new resident could be simply coming into the centre looking for English language courses, or may need to be steered towards the counselling needed after living in a war-torn country.

Ambtman applied to join the Edmonton Police Commission in 2016, but wasn’t accepted.

“Since I arrived in Edmonton, I’ve wanted to make a difference in Edmonton. I made it my mission to get appointed.”

So, he learned what he could from not getting in and, in 2018, was accepted. As someone who works to help newcomers settle in the city, he has hope that new chief Dale McFee will bring systemic changes to the EPS. Ambtman likes what he’s seen so far — that the police understand that they need to work with social agencies and healthcare providers, understanding that poverty, mental illness and addiction are all root causes of crime.

He has seen refugees who fear Edmonton police because, well, police were something to be feared in the countries they fled. He believes that the onus is on the police to work with new Canadians, to explain their roles, to make people feel comfortable in their presence.

Ambtman admits that it’s a “big challenge” that so many newcomers have arrived in the city in a short period of time. Larger centres like Toronto and Vancouver have established infrastructures for dealing with influxes. One thing Edmonton needs to do is shake the prairie-town mentality. While the aw-shucks, gather-at-the-arena stereotype still exists, it doesn’t reflect a multicultural, cosmopolitan Edmonton.

“We aren’t small,” says Ambtman. “We are large. We are cosmopolitan. What worked for Edmonton long ago is no longer our reality.” — Steven Sandor

Ryan O’Flynn, a former chef at The Westin Edmonton and winner of the 2015 Canadian Culinary Championships, fell in love with Europe when he went there 14 years ago, to explore the food scene in England and Wales, and returned to London this past summer, this time for good.

Shawna Pandya is a general physician, instructor of the Operational Space Medicine course with the project PoSSUM and a citizen-scientist astronaut candidate and aquanaut.This fall, she embarked on her first under-water mission, NEPTUNE, in the Florida Keys.

Todd Babiak’s novel, The Garneau Block, has been turned into a stage play by Belinda Cornish (premiering at the Citadel Theatre in March), but the author and entrepreneur now works as a CEO of Brand Tasmania, an

organization that strives to promote and develop the island state’s brand locally and globally.

This article appears in the November 2019 issue of Avenue Edmonton