Illustrations by Lee Nielsen

It’s a Saturday night in the big city and chaos is unfolding on the streets. There are reports of gunfire outside a downtown bar, multiple victims. As police respond, another call comes in: carjacking at gunpoint, west end.

In a secure room at a secret location in the city, police and criminal intelligence analysts map the events as they occur, live, on a giant monitor. A similar description emerges of the suspect in both the shooting and the carjacking.

The intelligence team quickly pushes an alert to frontline officers. A single text describes the make and model of the stolen car, the suspect’s age and build, and two photos – one from police-registered CCTV, the other a police mug shot, which facial recognition software has identified as a probable match for the image captured by the surveillance camera.

Fifteen minutes later, as paramedics still tend to the downtown gunshot victims, a southside patrol car tries to pull over a driver who’s run a red light. The car speeds off. The officers enlist help from police helicopter Air-1; their description of the vehicle matches that from the carjacking, triggering an alert in the secure room. The duty officer readies the Tactical and Canine units for a high-risk takedown.

Moments tick by. New 911 calls pour in, reporting a serious crash in the south. Looks like the same vehicle. The occupants run away. But between the helicopter and the police dogs, there’s nowhere to hide.

Back in the secure room, the team watches a live feed of the arrest from Air-1. One of the suspects is the man in the mug shot.

It’s been less than an hour since the shooting. The police are in control and the investigative case work has already begun, thanks in large part to the new technology in the secure room.

This hypothetical circumstance takes place in a hypothetical room called an Operations and Intelligence Command Centre. The command centre would cost $5.7 million, and the Edmonton Police Service really wants one.

There is a fundraising campaign in the works, along with a plan to make it happen within a year. Edmonton police Supt. Chad Tawfik is in charge of the project. He describes it as “a centre that’s focused on a 24/7 response to ongoing and emerging events, both from an operations standpoint and an intelligence standpoint.”

More commonly called “real time” crime or intelligence centres, such facilities have been opening across the United States and Canada over the past decade. Tawfik visited four real-time facilities – in Los Angeles, Boston, Surrey, BC and Calgary – while researching his Edmonton proposal. At each one, the feedback was identical.

“They can’t imagine not having it now. They are extremely effective,” says Tawfik, a 21-year veteran of the force and superintendent of the EPS strategy management division.

Criminals “will use and exploit technology to the best of their ability,” he adds. “We have to evolve with it from a technology standpoint.”

Given the near blanket web connectivity of Canadian culture, some may be surprised by what police aren’t yet doing.

“I think the public probably thinks we do more than we actually do,” Tawfik says, referring to the extent to which Edmonton police use technology.

He says the new data centre will give the police a fuller picture of what’s going on across the whole city at any given time, and also help police stop crime sprees that happen over days or weeks.

“If I’m a victim of crime, or going to be a victim of crime, I expect the police to do everything in their power to connect the dots in advance, or shortly thereafter.”

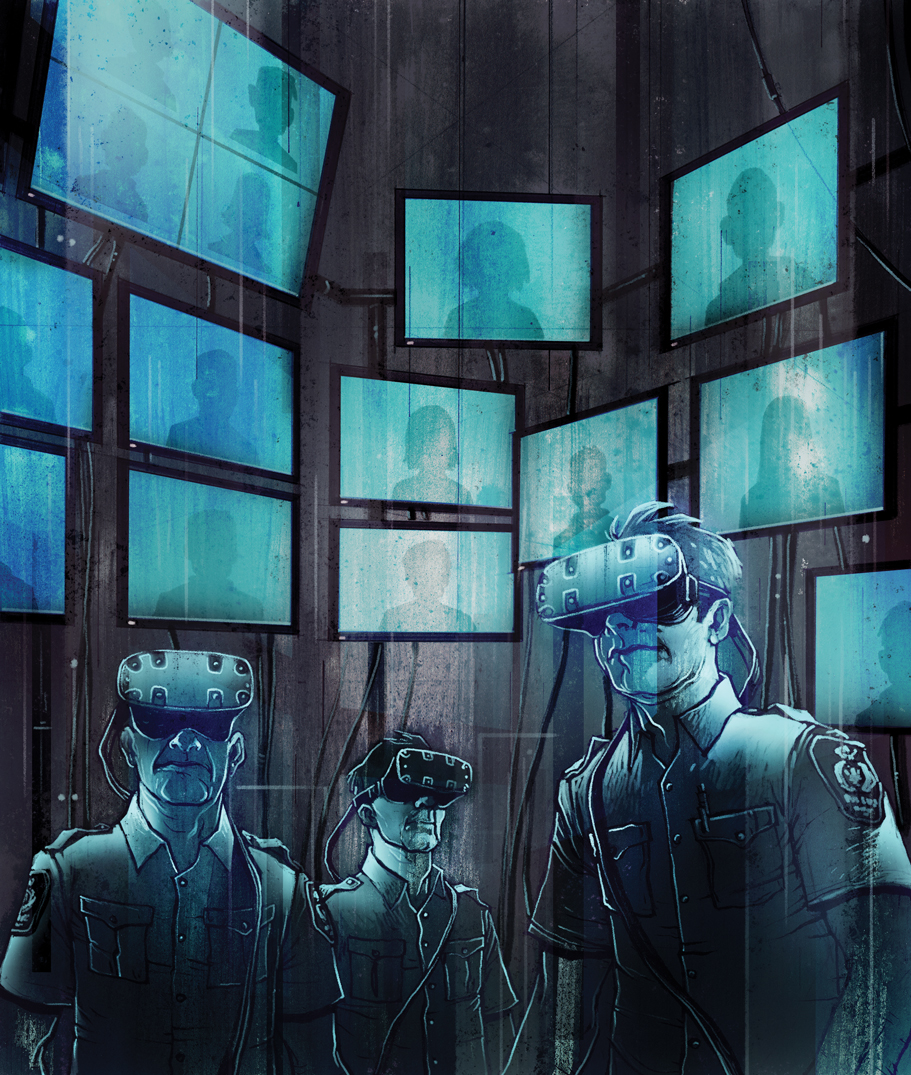

Operating 24 hours a day, the proposed command centre would have a wall of TVs and a small staff including the duty officer and criminal intelligence analyst. Their task would be to monitor what’s going on across the city and provide actionable intelligence to the front lines.

The lifeblood of the command centre would be data, gathered from existing and proposed – and in some cases, controversial – sources: body-worn video, vehicle-mounted video, surveillance cameras, licence-plate readers and, later, facial recognition software.

The centre would also have a new data mining capacity, to sift through the police service’s vast cache of information, and to scan open source information in the public realm, such as social media content. With permission, CCTV content could be accessed from businesses and schools in real time, to help police in tactical situations. Other surveillance cameras could be registered for police use. The centre would also be linked with Air-1, the police helicopter.

Command centre staff could push intelligence to the smartphones of officers on the street.

The intent is for police to be able to act in “as close to real time as you can be,” says Tawfik. It’s also to help police predict and prepare for what might happen next.

“I think about the next victim walking down the street right now,” he says. “If I can do something to intervene with that offender before they do the next crime, that’s important to me.”

But while Edmonton’s business case is still awaiting approval, it’s already ringing alarm bells in some quarters. Some of the technology police are proposing to use has drawn criticism from civil liberties and privacy advocates.

Take facial recognition software. In October, Georgetown University’s Center on Privacy & Technology released a study called The Perpetual Line-up: Unregulated Police Face Recognition in America. It found half of all American adults – some 117 million people – are in face-recognition databases, and that police use of those databases is virtually unregulated. In an article published on the tech website Ars Technica, study co-author Alvaro Bedoya called the phenomenon a “massive virtual line-up.”

Adam Molnar, a lecturer at Deakin University in Melbourne, Australia, and a member of the Canadian Network for Research on Terrorism, Security and Society, says the effectiveness and impacts of these innovations are under-researched.

“In many respects I think police are seduced by new technological developments, the idea that they are going to be the silver bullet. I think if you’re looking at a massive budgetary expenditure, there’s research needed to determine necessity and effectiveness.”

Linda McKay-Panos, executive director of the Alberta Civil Liberties Research Centre, understands the desire of the police to solve and prevent crime, but warns of some of the information gathering tactics laid out in the draft plans.

“What if somebody else put something on your Facebook page, or created a profile of you?” she says. “If the police are assuming that information is accurate and you don’t even know they’ve got it, you wouldn’t have a chance to correct it. They have the tools to find it, and you don’t. If you’re in the same frame as a criminal, they could assume you hang out with criminals.”

Data retention and storage are also causes for concern.

“In Canada, a lot of people would say, ‘I have nothing to hide, so I guess I don’t mind (being watched).’ What they don’t understand is the potential use of that data if it gets into the wrong hands,” says McKay-Panos.

This notion – that benign information in the wrong hands can be twisted to corroborate a nefarious narrative – weighs heavily not just on civil liberties and privacy advocates, but also on marginalized populations.

Molnar says predictive policing models can upend the presumption of innocence by shifting the burden of proof onto citizens.

“Just because technology is involved doesn’t necessarily mean the process is objective,” he says, adding that poor quality data can lead to problems such as those associated with profiling.

Tawfik knows technology isn’t perfect, but doesn’t believe the new command centre will lead to profiling.

“I’m not concerned over issues on profiling, because what I’m focused on is criminal behaviour. I’m focused on who is exhibiting criminal behaviour – on identifying people who are acting in a certain way,” he says.

He also seeks to assuage fears about facial recognition software collecting random images of people walking down the street, for example.

“That wouldn’t pass the public privacy test to just be randomly scanning the environment like that.”

In fact, Tawfik is keenly aware of the delicate balance police have to strike between protecting the safety of the public and protecting their privacy.

“It’s about public safety, not invading privacy. It’s going to be our guiding principle that we follow the rule of law and ensure what we do will stand that test. If it doesn’t, then our effort is really for naught.”

At its annual gala in October, the Edmonton Police Foundation – the fundraising body that successfully championed the purchase of Air-1 in the early 2000s – launched a $6-million fundraising campaign for the new command centre. Whatever the foundation manages to raise will offset the cost, with the remainder coming from taxpayers. Tawfik will make the case for funding to the Edmonton Police Commission this month.

Foundation chair Sol Rolingher says it would be “unconscionable” if a major incident occurred because police lacked the best and latest technology.

“We have international people flying in and out of here all the time. We’ve got targets,” Rolingher says, citing refinery row, the new arena and West Edmonton Mall.

Of the command centre, he says, “We believe in it, we’ll do everything we can to make it happen.

“You and I will have a much calmer, safer life by having this present.”