The idea is that they’d all get equal treatment in our pages. It’s a long campaign, and it’s a long way to the top if you want to rock the electoral rolls.

Nine of the candidates agreed to be interviewed. Current city councillor Mike Nickel didn’t return our calls, and our writer even went to his campaign office. Nickel also didn’t return our calls when it came to the photo shoot. Rick Comrie agreed to be interviewed, but told us that his tire business was so busy, that he couldn’t make time to be photographed.

This is an awfully big choice. This will be the post-COVID council, one that will likely deal with funding shortfalls and some tough decisions to make about programming, infrastructure and how to maintain services. We hope you’re thunderstruck by the tough decision that you, as a voter, will have to make.

Abdul Malik Chukwudi may consider himself an insider, but it’s definitely not the kind that you would usually associate with a mayoral candidate.

Trained as a civil engineer, Chukwudi, 49, worked for the City of Edmonton prior to announcing his candidacy for the mayor’s seat. He stepped away from the position due to it being a potential conflict of interest to work for the City while also running in a municipal election, but also because it might have given him a leg up on the other candidates.

“The Election Commission felt it probably [was] not fair to other candidates because I’m an insider, right?” Chukwudi says. “I know the infrastructure, the construction, all the detailed information about how much third-party con-tractors cost.”

Chukwudi’s familiarity with the inner workings of Edmonton’s infrastructure is also why he felt compelled to enter the mayor’s race, despite the move being somewhat uncharacteristic for him.

“There’s no one who has any political experience in my family. Even when I announced that I was running, my parents were like, ‘Oh my god, wow,’” Chukwudi says. “But working for the city opened my eyes to a whole lot of things that need to change.”

In particular, Chukwudi points to what he calls a poorly thought out LRT expansion plan, crumbling roadways and rapidly rising rental prices resulting in chronic homelessness. But, most of all, Chukwudi is critical of a lack of investment in tourism and enterprise, and its effect on Edmonton’s diminishing global status.

“We need to open Edmonton for business,” he says. “My daughter and my son say that once they graduate from high school, they don’t want to live in Edmonton. Most of our university graduates, after graduating from the U of A [or] NAIT, try to find work in the United States, Australia or the United Arab Emirates.

“We need to make our city into a place that people want to be, [where] people want to come here and [they] don’t want to leave. When you tell someone where you come from, you’re proud and you say, I’m from Edmonton.”

Chukwudi calls me from the cab of his truck during a bit of downtime — he’s working as a supervisor for a friend’s construction company while he runs his campaign — and he makes it clear that this is where he feels most in his element. “I’ve been in coveralls my whole life,” he says, and whether that involves putting spikes in the ground, repairing sidewalks, or working on city snow removal, he definitely doesn’t think of himself as an “office engineer.”

That’s also the kind of hands-on approach that he wants to bring to Churchill Square, and a characteristic that he believes sets him apart from some of the other candidates.

“When you think as an engineer, you think of solutions,” Chukwudi says, “You know, I listen to Mike Nickel [say] the LRT is a horrible thing. But, Mike, what’s your solution?”

With regards to his own solutions, Chukwudi is sparse on details, although he is bullish about the need for the city to invest in sports, post-secondary education and tech in an attempt to improve attractiveness and retention. He is also open to taking a more data-driven approach to problem solving, whether that means conducting citywide studies on the effectiveness of photo radar, or visiting international hubs like London, England and Hong Kong to learn ways to improve transit.

Chukwudi also has his sights set on a political future beyond City Hall. He says that he has already been in contact with some of the province’s major political parties, and even if he doesn’t win this October, he suspects this won’t be the last time his name pops up on a ballot.

“I don’t think I will walk away from politics,” he says. “I don’t know if I’ll go federal or provincial, [but] I’ll continue to try. But so far, from what I’ve seen, I’m the best candidate out there.”

— TOM NDEKEZI

Driving along the streets of Edmonton one snowy March day, Rick Comrie came upon a disturbing scene.

An ambulance carrying a patient was stuck in the snow on a city street. A crowd had gathered to push it out. Ultimately, Comrie says, another ambulance had to come and rescue the stranded patient.

As the owner of mobile tire company TireBoys, Comrie had been driving the city streets all day.

He says bike lanes had been cleared of snow, while this street had not.

“Everywhere I saw bike lanes had been cleared. We live in subzero temperatures eight months a year and we’re building infrastructure that’s harming the foundation of what we need in our society, which is fire and ambulance.”

For Comrie, 64, a father of two grown sons, the tableau was a symptom of a flawed ideology that has caused the city to lose its way and make “misplaced” investments into LRT and bike lanes.

The incident “was the hammer in the nail” of his decision to run for mayor.

“And what’s happened since then is the integration of bike lanes. The obstruction on our roadway system has snowballed,” he says.

Comrie comes from a long line of Edmonton entrepreneurs, stretching back to his great-grandfather in the 1940s.

“I work eight-to 12-hour days, and I wear boots at work,” he says, adding that his working-class audience will know why that’s important.

“I’m a businessman, but I’m also a worker.” He says the LRT has been “a boondoggle and a billion-dollar blunder” and bike lanes are just as bad.

“They’ve changed the downtown to eliminate automobiles,” he says. “It’s full of bike lanes. It’s so crazy, it’s so far whacked, it defies logic.

“The money is in the car,” Comrie insists. “Who’s the spender? Does a bicyclist go and buy sporting goods, or furniture, or clothing? Or are they just out for a ride?”

Meanwhile, business owners suffer because bike lanes and LRT lines block access, he says, adding that he once counted 60 stopped vehicles waiting for an LRT train to go by.

“If you build infrastructure that obstructs spending, what is the result? The word I can use is catastrophic,” he says. “Every bicyclist could be looked at as taking a job away from someone. I’m not anti-biking, but this is crazy.

“They’re pushing upon you a society you don’t want,” he says, referring to leaders at both the municipal and federal levels. “That as a taxpayer, you fundamentally won’t be able to pay for.”

If elected, Comrie would immediately stop work on all LRT construction pending a plebiscite to ask Edmontonians whether they actually want it.

Comrie also plans to stop municipal spending, focus on roadway functionality, and strike a committee on bike lanes.

“You have to run a tight ship. You have to find ways to cut back. The spending is the issue, and fiscal irresponsibility.”

Come election day, he’ll be there with boots on.

— ELIZA BARLOW

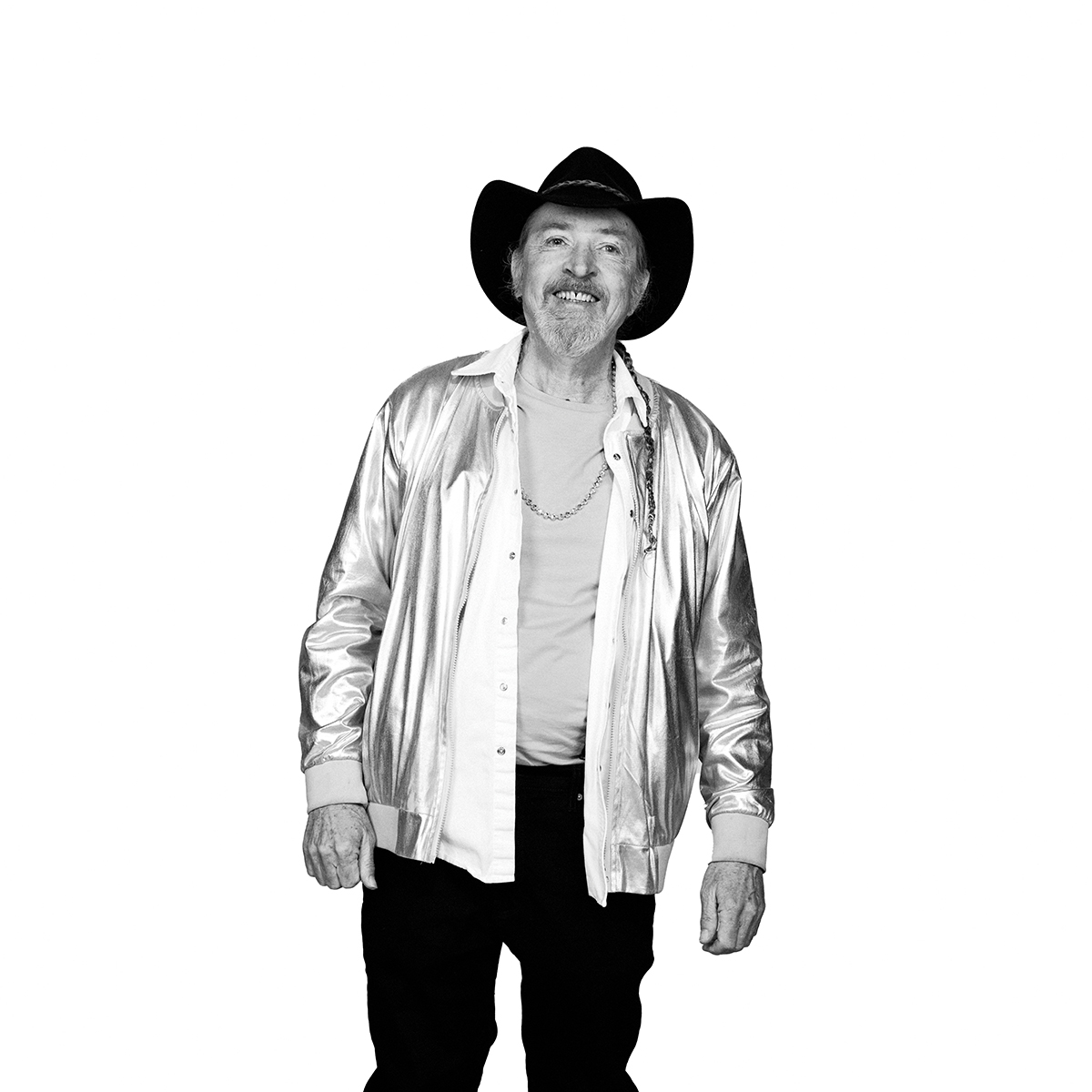

In the late ’70s, Brian Gregg’s bandmates used to call him “Breezy” for his ability to talk about anything. Since then, the nickname, along with his ability to shoot the breeze, stuck. Nowadays, as a mayoral candidate, he’s still talking. But instead of just chatting about guitars and musical notes, he’s also discussing platform points and voter turnout.

Over the course of many decades, he’s worked as a musician — one of his bands once opened for Led Zeppelin — while always keeping an eye on politics, becoming especially engaged in recent years through volunteer work.

He ran for mayor back in 1998 — he finished with just over one per cent of the vote — and now he’s back with a completely self-funded campaign, or “quest” as he calls it, that focuses on equality, economic responsibility and forward-thinking policies. “With the climate emergency and the pandemic, it’s no time to fool around. We have to be smart by creating a caring economy,” says Gregg.

He has several ideas for going forward, starting with taking big money out of politics, hence his decision to fund his own campaign and rely on volunteers. One of his big concerns is that politicians sometimes run government like a business, resulting in short-sighted choices. “It should be run like a rock ‘n’ roll band, where taking care of business is important, but what’s most important is that everyone’s having a good time.”

Instead, he’d like to see more options for affordable housing, improved resources for the homeless, a focus on improving library services and unionization of all essential workers — even though some of those goals would need cooperation from the federal and/or provincial governments. Gregg has a vision of an emergency services campus that would include a homeless shelter, a daycare and a library that all connects with the Royal Alexandra Hospital. Free transit is also on the platform as is a focus on the reduction of crime and mental health support for those experiencing addictions.

“We’ve been building a lot of roads but we… can’t take proper care of people who are in trouble,” he says.

He’d also like to see more products produced locally with the goal of more jobs and less environmental burden. Local food, he says, could be produced in a commercial greenhouse district that circles the outer limits of the city, inspired by agricultural production in the Netherlands. “We have to look around the world at what other countries are doing,” he says.

One of the big ways of reaching his goals, says Gregg, is through an increase in taxes, as higher taxes are the norm in many Scandinavian countries.

“I don’t think it’s realistic to have this race to the bottom and always try to have the lowest taxes in anywhere on the planet. The kind of democracies that I look at and respect are ones where they have higher taxes than we do, and where they take better care of the people,” says Gregg. “Like, this is a mean economy that we live in. Very, very mean.”

Gregg hopes the new ideas he brings to the race will inspire everyone, including a whole new demographic to come to the polls — those who maybe hadn’t been previously engaged in municipal issues as they hadn’t felt represented — resulting in a shift in priorities that could help those very people.

— CAROLINE BARLOTT

Some might think now is a strange time to want to take on the job of mayor of Edmonton. An unprecedented global pandemic has hobbled the city’s economy. Its finances will be squeezed for the foreseeable future by provincial budget cuts to municipalities.

But Kim Krushell says it was the pandemic that propelled her into the mayoral race, and she’s ready for the challenge.

“When the pandemic hit, all of us were thinking about the future and how we’re going to get through this, in terms of economic recovery,” she says.

“I started thinking about what characteristics we’re going to need in terms of the next mayor. I care deeply about our city and our residents and our collective future and I’m a booster for our city. To get through this pandemic we’re going to need that type of mayor.”

Krushell, 54, was a three-term city councillor for Ward 2 before leaving politics in 2013 to spend more time with her family. At the time, her in-laws were ill and her son had just entered his teens.

She grew up in Laguna Beach, California, and moved to Canada after meeting her husband, Jay, as exchange students in South Korea. She’s lived in Edmonton since 1993. She co-founded, with her husband, two tech companies since leaving council, and says she has the “right mix” of public and business sector experience.

Krushell built her election platform around three questions: How can the city improve? How can it innovate and encourage business? And how can the city help its residents?

“The top priority is to get through the pandemic. Economic recovery and being open for business are going to be critical because we know a lot of our businesses are suffering,” she says, adding core services and maintenance and supporting the most vulnerable are her other main platform fronts.

Despite past ties to the defunct Progressive Conservative Party, Krushell calls herself a centrist candidate, who is focused on “getting wins for Edmonton.”

Her experience matters in an election that will elect many new faces to council, she adds. Being able to get up and running from day one, rather than learning the job, “is an advantage that I certainly bring.”

Krushell’s approach to the council table will focus on consensus building.

“I feel that that is going to be really necessary given that we have so much turnover happening on this council coming up. So I think that (my) knowledge and that history is also really important.”

An incoming mayor also needs a solid understanding of the fiscal realities the city faces, following massive reductions in provincial grant funding and the delay of a long-term fiscal framework with the Government of Alberta.

“I’m assuming we’re not going to have as much money as we’ve had in the past and we’re going to have to do more with less,” she says. “We’re going to have to be really nimble to figure out ways to continue to provide services that are needed and juggle the realities that we’re going to be facing fiscally.”

— ELIZA BARLOW

Augustine Marah is a man of many hats. Teacher, activist, and writer are just a few of his titles. He hopes the next one will be mayor.

Marah has worked in municipal, provincial and federal politics since 1984, campaigning for mayors, Members of Legislative Assembly and Members of Parliament. Now, he’s campaigning for himself.

Marah’s involvement in politics came only three years after moving to Edmonton from Sierra Leone in 1981. He came to Edmonton with only $25 in his pocket and completed his undergraduate degree at the University of Alberta in two years.

He later went on to teach elementary school, junior high school, senior high school and post-secondary before opening his own accredited private school called Alberta International College.

“I am a visionary, and I have a passion for working with other leaders with whom I have a common purpose for the benefit of all,” says Marah on his website. “As a retired teacher and school administrator, I also love to bring out the best in people’s potential and help others find their voice, especially our young generation.”

Community and education are at the heart of everything Marah does, and are the backbone of his candidacy. He’s committed to community building and has worked with organizations such as the Mennonite Centre for Newcomers, Edmonton Multicultural Coalition and Camrose International Institute.

He wants to reciprocate the generosity he felt from the Canadian community when he moved to Edmonton by making it a better place for everyone.

“I was raised in a family of strong traditional values and principles of hard work and contribution to society,” says Marah in a campaign video posted to his website.

“I translate these values and principles in the way I live.”

How do these values and principles translate into Marah’s plans for Edmonton?

“I am interested in finding innovative ways to increase, improve, and to diversify job creation for the prosperity of Edmontonians with the collaboration of all the city’s councillors,” says Marah.

Marah also wants to continue Don Iveson’s efforts to decrease the homeless population and improve their quality of life.

“I want to make it abundantly clear that I am ready, I am able, and I am willing to listen to you, to work for you, and to work with you to take the city to any heights we are able to take it.”

— KATRINA TURCHIN

Michael Oshry is running for mayor as one part incumbent and one part rebel. He was elected to council in 2013 and decided to leave by 2017. A one-term councillor by choice is a rarity in Edmonton. But after four years of commenting from the sidelines — he’s very active on Twitter — Oshry wants to return and lead.

Oshry was born in South Africa and his family immigrated to Edmonton. He found the city welcoming of entrepreneurs. In the ’90s he bought and ran a former coffee shop on 124th Street. He then opened the first Remedy Café, in Garneau, although he would later sell the coffee shop. “That was me, that was my business,” Oshry says, aware his name isn’t tied to the wildly successful company. “That was my brainchild.”

By the late 1990s, Oshry and his brother, Clive, opened Globex. Oshry had become involved in foreign currency exchange and saw an opportunity to offer currency exchange services. He was right. By 2000 they opened their second office in Calgary. By 2003 they bought into the Looby Block building on Jasper Avenue (now home to the Wee Book Inn) for their headquarters, and, by 2006, they had 23 locations on three continents. In 2010, just before Oshry ran for council, he told the Edmonton Journal, “We want to be the biggest player in the world outside of the banks.”

Oshry does not lack for ambition.

Today, his company is still headquartered in Edmonton, though re-named FIRMA. Oshry is its sole shareholder but has hired a CEO, and it has offices in four countries, a few hundred employees and transactions at $12 billion per year, according to Oshry. It is not the biggest player in the world, to go back to his 2010 goal, but FIRMA is the largest private exchange company in Canada, he says.

But with all that wealth, why is he running? Oshry, who’s 53, speaks a lot about qualifications. He’s got the unique experience of having served on council but not sitting for multiple terms, he says. “I wasn’t in there for decades which I’m not sure is an asset. I know how it works and I know how to build a business and lead, and I know how to bring together people of different viewpoints, so I think I’m pretty qualified to deal with these challenges that we’ve got coming ahead.”

What are they? “For the first time in a generation, I don’t think it’s clear where our success is going to come from,” he says.

“I’m talking about economic success and also social success.”

Still, many will wonder why Oshry left in 2017 if he wanted to steer Edmonton forward. During that 2013-2017 term, some referred to him as the “Bruce Wayne of council” — independently wealthy and willing to call out problems as he saw them. Oshry says he just had to leave. “I was very frustrated for the last couple of years. Council wasn’t working together. The priorities that council had at the time, I wasn’t in agreement with all of them. I’m very much a collaborator and I felt there was no collaboration. I got very frustrated with that.”

The mayor’s job is to spend time with councillors and build collaboration, he adds, and here you must read between the lines. That “has not been happening for the last decade,” he says.

“I think we’ve got to get back to that place where the government of Edmonton is more of a servant rather than the master,” Oshry says. “We’ve got to bring back a source of pride in the city and I think that’s been lacking over the last few years. My vision is for Edmonton to be a well-run, prosperous and attractive city. I’m really doing this to give back to the city, and it sounds a bit hokey, I get that. But there needs to be a refresh on

the vision.”

— TIM QUERENGESSER

The campaign worker takes my name and number but I don’t expect to hear back from city councillor and third-time mayoral candidate Mike Nickel. He launched his campaign via Facebook Live in late January and did not take questions from reporters. I already sent two emails and left two phone messages requesting an interview for this story… crickets.

But I drop by his campaign office early one afternoon anyway to see if I can catch him. He operates out of a vacant spot that once housed a restaurant in the west end. Tables and chairs have been pushed back and stacks of lawn signs crowd one wall. Backdrops for photos and live streams fill the foyer. The office is quiet and Nickel is not in.

He has a long history in municipal politics, having run and lost in 1998 and 2001 before breaking through with a victory in 2004. He lost his council seat to current Mayor Don Iveson in 2007, finishing third of four candidates, but successfully returned in 2013 and was re-elected in 2017. Nickel also took a run at provincial politics in 2019, losing the United Conservative Party nomination in Edmonton-South to Tunde Obasan, who subsequently lost in the general election to the NDP’s Thomas Dang.

Nickel is known as a conservative voice on council, championing small government, low taxes and reduced regulation. His campaign platform focuses on the economy, jobs and municipal debt. He’s opposed to bike lanes, the West LRT and Edmonton’s status as a sanctuary city.

Nickel is also critical of the City’s recent efforts to end homelessness, calling them expensive and misguided efforts that lump people who are homeless because of afford-ability issues together with those with mental illness or addictions. “Why are we throwing money into the people that need treatment and treatment beds and throwing them into housing?” he asked in a recent Facebook Live. He calls for a voucher system in which “the money follows the client. That’s the really important part here, and we have to keep the paperwork to an absolute minimum. Overhead in government is a nasty thing. They’ll tack on stuff and create more bureaucrats.”

Nickel has allies on council for some of his policies, but his ability to work with others is in question. Last August, the City’s integrity commissioner recommended that he be reprimanded for misleading social media posts relating to City bike-lane decisions and for posting a cartoon of Councillor Andrew Knack throwing money on a fire. The commissioner held that while councillors can express opinions strongly, with passion and even with exaggeration, Nickel’s contributions were disrespectful, contained personal attacks and misleading information, lacked decorum and were contrary to the City’s code of conduct. Nickel said he was asserting his freedom of expression rights and should not be censured. He avoided sanction by council only because just eight of the 12 councillors voted in favour, one short of the necessary supermajority. Nickel’s response has been to repost the offending material, criticize the cost of the integrity commissioner’s investigation, which he pegged at $50,000, and say he wouldn’t be intimidated or silenced by unelected officials. This has led to more charges against Nickel (see footnote).

So questions remain about how Nickel will be able to implement the policies he prefers in the consensus-driven realm of municipal politics and his ability to negotiate with the provincial and federal governments — questions that will, for now, go unanswered.

— MICHAEL GANLEY

Just as the issue went to press, the city’s integrity commissioner released a new report stating Nickel violated council rules in two separate matters. The first regards allegations of inflammatory social-media posts sent in retaliation to individuals who had made complaints against him in the past. The second, relating to this election: He is accused of collecting e-mail addresses as part of his city councillor duties and using them for campaign purposes. The matters had yet to go before council at press time.

At 57, what stands out to Amarjeet Sohi as he looks back is the community and compassion. The community was the extended farming family he grew up with in Banbhaura, India, and the older brother who sponsored his move to Edmonton at 18.

The compassion came years later, after he returned to a village in the Indian state of Bihar, organized a protest advocating land reform, was arrested, tortured and spent the next 21 months in jail (18 in solitary confinement). “Even in the prison, there were people who showed me compassion, who helped me connect to the outside world. They risked their jobs, but they still did it.”

After returning to Edmonton, Sohi got to know the community well as a bus driver, before his first successful run for city council in 2007, where he sat until becoming a member of parliament in 2015. He cites the Yellowhead conversion project, Fort Edmonton Park’s expansion including the Indigenous Peoples’ Experience, and the 50th Street railway crossing, as examples of how he helped direct federal funds to benefit Edmontonians. “What drives me is the need to build other people’s capacity to succeed,” he says.

There’s a lot that can be done with the City’s over $3-billion budget regarding issues of addiction, mental health and homelessness, he says, especially with help from the provincial and federal government. But the “convening power of the mayor’s office is significant in how it can pull all the people from the community together to carve a path forward on engaging with the federal government. Along with bud-get tools, the mayor provides leadership to the community so that we aren’t working in silos, but are building that collective approach. That’s where I will focus.”

He acknowledges the difficulty in bridge-building with ideological opposites, but as someone who built relationships with those meant to keep him in prison, he knows how to start. “When we are dealing with people, we need to deal with them from the point of trust. I did that when I worked on the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion and we negotiated and engaged with 129 Indigenous communities from different backgrounds, who had different expectations and different needs. And you can work with partisan opponents if you come from a point of trust.”

A few years after he first arrived in Edmonton, Sohi joined a Punjabi theatre group. When he later went back to India, it was to study with famous playwright Gursharan Singh and learn the most community-based type of theatre there is: street. “I wanted to learn more about the importance of art in bringing social change, and I wanted to learn this specific technique where you go to the street corner and perform with a group of people. The power of theatre is that it provides you an opportunity to actually live in other people’s shoes. It broadens your understanding, your perspective of the world, and helps you become a better person in your community.”

— CORY SCHACHTEL

In mid-March 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic hit Edmonton, Diana Steele began to post “check-in” videos on the community Facebook page she runs — sharing updates on the rules, reminding people to wash their hands, and inviting them to call her if they needed anything.

She continued to post the check-in videos every day as the virus tightened its grip and shut down normal life in the city. As of mid-April 2021, she had missed only one day out of over 400.

“I said I would go until the end of the pandemic no matter how sick people are of me,” Steele says during an interview in End of Steel Park, as traffic whizzes past on Saskatchewan Drive.

“I do the videos because I know there are people who live alone, who have no one to look out for them and check in on them, and I let people into my life every single day. It’s been wonderful. I tell people to call me any time, and they do. I get a lot of really positive feedback from the target audience I’m trying to reach.”

Steele, who’s president of the Crestwood Community League — a role she’s held for over six years — is hoping her track record as a listener and community leader will help her become Edmonton’s next mayor.

Prior to deciding to run for the top job, the 45-year-old mother of two — who also works for a local hospice society and is a substitute teacher — was becoming increasingly concerned about partisan politics creeping into the municipal sphere. “We look at issues like infills and potholes. There should be no right or left considerations involved in those decisions,” she says. When someone she had been urging to run for mayor ultimately said no, Steele decided to put herself forward.

“I’m doing it because I think we need a leader like me — a female, Métis leader who’s kind, compassionate, transparent and works collaboratively with others. I’m not here to further my agenda, I have no further political aspirations in any way. I just genuinely want to help people,” she says.

“And I want to close the divide. The city is becoming more and more divisive — we have a lot of concerns around racism.”

Steele, who grew up in Clareview, has several points in her platform. The first three she plans to focus on are saving Edmonton businesses — particularly in the wake of the pandemic — building community and ending homelessness.

“If we can make sure our economy is strong, make sure our homelessness has been solved, and make sure our families feel connected with one another, I think we’ve got a really excellent city to build for the future,” she says.

As provincial budgets continue to squeeze cities, Steele says finding ways for the city to become more self reliant will be a priority.

“Like, I love the idea of putting in the gondola. It’s an idea, it’s someone who wants to try, it doesn’t cost the city anything, so why not?

“So, more ideas like that — the crazier the better.”

— ELIZA BARLOW

Cheryll Watson knows you don’t know her. “I’m a first timer here,” she says, as we talk in early April. “While I was born and raised here, and worked in the innovation ecosystem, that represents probably 10,000 people I know. There are [candidates] that have done public-sector work. They have an edge over me. People have seen their names before.”

You’re definitely aware of Watson if you’re in that tech bubble, though. She worked for 15 years for Intuit, in Silicon Valley, but flew between there and here to keep her base in Edmonton. After that she joined the Edmonton Economic Development Corporation, and then headed Innovate Edmonton for four years. The legacy is her lingo and approach — both are tech but also focused on growing city fortunes. Watson uses terms like “inflection point,” “impactful,” and “co-creation” to express her ideas for Edmonton. She talks of residents being the “customers” of the city.

Still, in a city where name recognition is powerful in municipal politics, Watson knows she has work to do. Who is she? Her website provides an open book into her past, in hopes you might find a connection. She was a server at Smitty’s at 15, she writes. Eventually, like many, she had the opportunity to leave and work in another country or city but chose to stay. She’s a “Northside girl” at heart, she writes. Today, she’s 53, married, and has four adult kids.

Watson’s first get-to-know-you strategy was to declare her intention to run in October 2020, months before others, to grow her profile. Strategy two is talk. She says she’s had close to 1,000 video chats (full disclosure: She had one with me) to hear what Edmonton residents want.

But why not first run for council rather than mayor? “I’ve spent the last four years serving and representing our city’s tech and innovation entrepreneurs — often in similar ways city councillors represent their ward constituents,” Watson says. “Working directly with city council and administration has helped me to see and understand how the system and processes work.”

On that front, there’s a weighty, almost Ted Talk-like quality to Watson’s platform. Proposal one is pure technocrat — to create a chief accountability officer, independent of city administration and council, to look to other cities to see how they’ve solved similar problems. Number two is a “central business neighbourhood” — faster permits for downtown businesses, free wi-fi for downtown visitors, free transit in the core. Oh, and free parking for an hour — this is Edmonton, after all. As a Ted Talk, it all might be called “Downtown Accelerator.”

Watson gets the mayor is but one vote on council. This makes how you work all the more important, she says. You set the vision but have to sell it.

On this point, if there’s criticism of the current mayor and council, it’s veiled yet specific. Watson says there’s some “joint responsibility” for the diminished relationship between the city and province. “It seems like Calgary is having better success with the provincial government. As the capital city, we need to get good at working with other orders of government.”