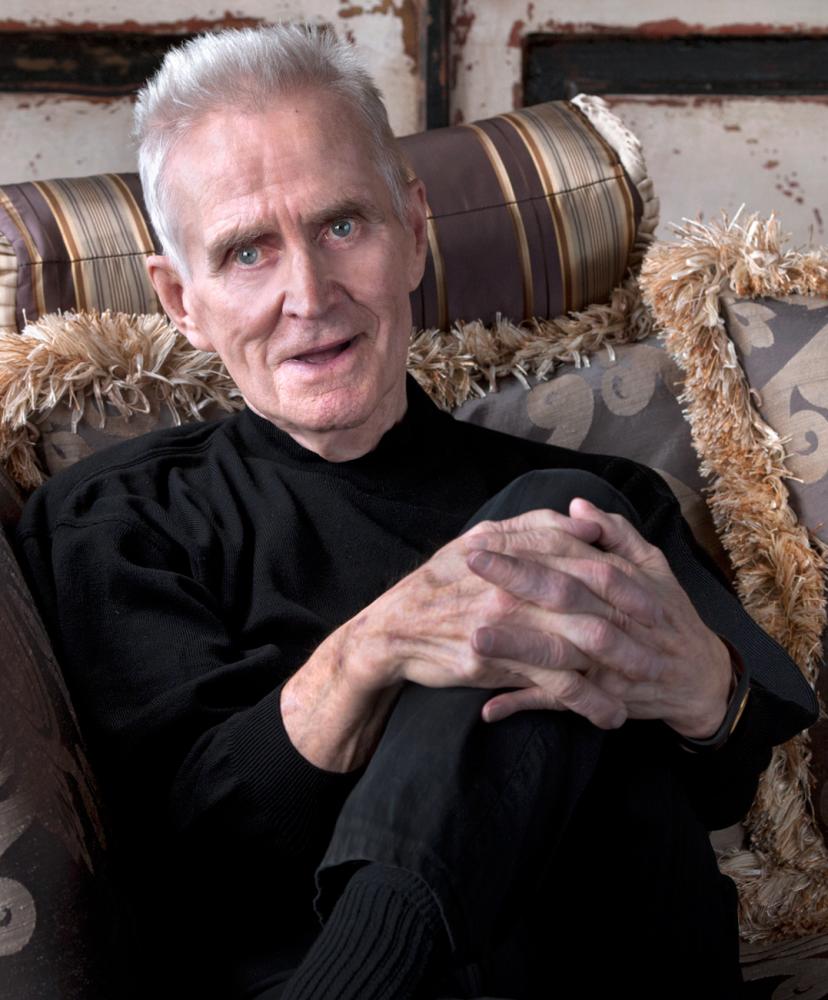

Gordon Buchanan was 69 years old when he noticed a cramp in his baby finger. Then, his handwriting got smaller. One day, as Buchanan headed off to work at a lumber mill in northern Alberta that he owned, his wife noticed something new. “I was giving him a hug as he was going out the door and I noticed a tremor in his back,” says Diane Kyle-Buchanan. “I asked him, ‘What’s that?’ and he said that he had had it for a while.”

The tremors and cramps turned out to be symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, a progressively degenerative neurological condition.

Now, Diane and Gordon are helping to create a centre for the many Albertans living with the condition – according to Parkinson Alberta, last year there were more than 8,000 cases in the province. The Buchanan Centre, scheduled to open by next year, will help patients with disease management. “The biggest thing you get is the fear. People who get the disease think, ‘Now what?’ We are able to take the fear away because we can help them manage the disease and make decisions sooner,” says Diane, who is on the board of Parkinson Alberta.

The Buchanans realized the need for a centre right from the beginning of their experience with Parkinson’s disease – the couple travelled to Phoenix, Ariz., to the Mayo Clinic, to see a neurologist after they learned there was a one year wait to see one in Edmonton. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta lists 122 neurologists in the province, as of 2013.

“For this population, it’s just too much work for them,” says Diane. “The thing I really want to work on is to take some of the pressure off of the neurologists so that, when their patients are diagnosed, they can send them here.”

The centre will offer 19 programs, and services such as counselling and speech therapy. It currently costs $48 million a year to provide services to people living with Parkinson’s disease, according to Parkinson Alberta.