You know them as crumbling, tacky relics of the past. But, in their heyday, strip malls were busy shopping areas just a few paces from home. They first emerged in Edmonton in the 1950s, when convenience was necessary for families who couldn’t afford more than one vehicle. People needed to do their errands on foot, whether that meant grabbing groceries or getting their shoes fixed.

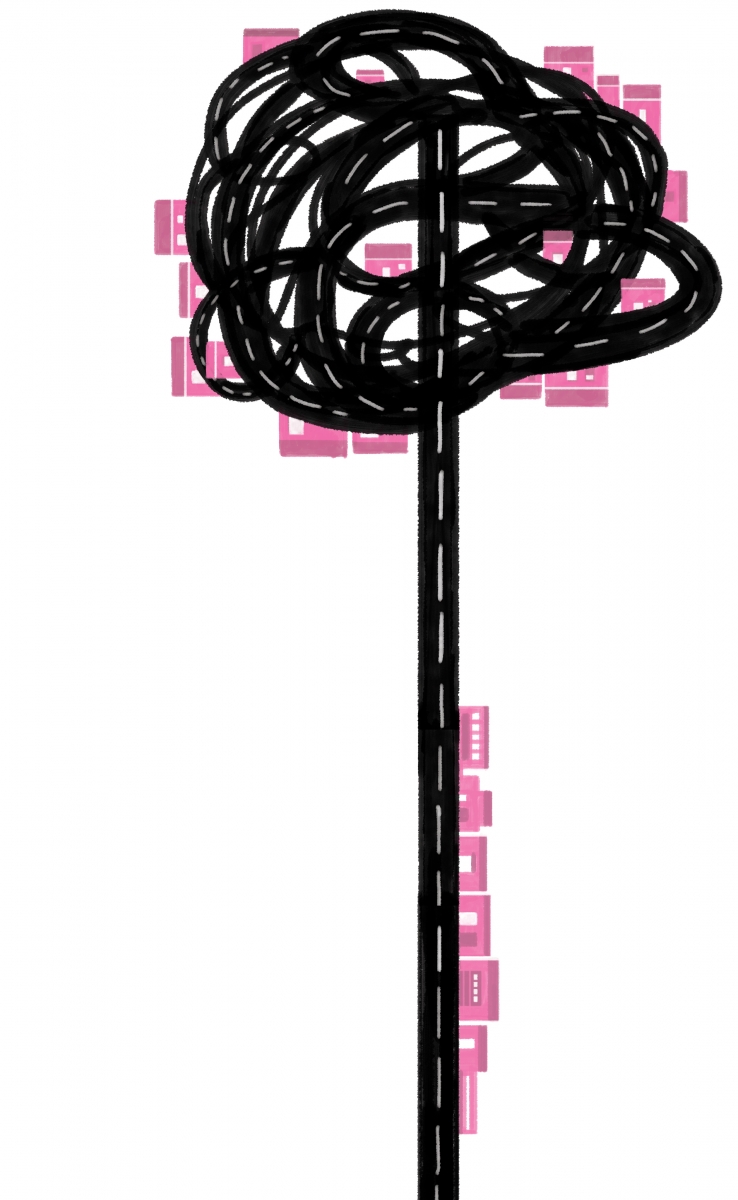

But, over the course of several decades, these neighbourhood hubs fell out of favour and into disrepair, as they did across North America. A big thrust of this change: Cheaper cars. When families were able to own two vehicles, they could move to cheaper, bigger houses in the ‘burbs. “We started to see more malls being built and fewer strip malls,” says City of Edmonton senior planner Wai Tse Ramirez. In older areas, residents began to drive past their local strip malls en route to the mall. While plenty of businesses survived, only a few thrived, and property owners had less capital to reinvest in building upgrades.

This has left more than 100 strip malls in Edmonton’s mature neighbourhoods limping along through the decades. This was the case in Ritchie, an established area on the city’s south side where families moved out in droves decades ago. “The houses in Ritchie are tiny, usually under 1,000 square feet, and that’s too small for most people,” says Laura Cunningham-Shpeley, who lives in the area and serves as community league president. The neighbourhood’s two strip malls – on opposite sides of 76th Avenue and 96th Street – have continued to keep tenants (including successful businesses like the Blue Chair Cafe and Acme Meats), but the tired infrastructure has frustrated residents for years. At least, until now.

After a couple of years of working behind the scenes, the community league, local businesses and The City of Edmonton are dramatically revamping the area’s two strip malls. Last year, Ritchie was one of three neighbourhoods chosen to take part in the city’s Corner Store Pilot Program, which provides funding to upgrade infrastructure inside and out, and improve the streetscape (sidewalks, landscaping, lighting etc.). The program also offers business development support for tenants as they re-launch.