St. Albert mission sits on top of a large hill overlooking the city. There’s a big Catholic church, a retirement centre and a chapel, built in 1861, that is Alberta’s oldest known wooden structure — the church of Father Lacombe. When I visit the site, there is construction where an old parking lot is being replaced.

Along the walkways on Mission Hill is the Founders Walk, a series of signs that describe the people who settled the area or made significant cultural contributions — such as Father Lacombe, Bishop Taché and Marguerite d’Youville, a widow who worked with friends in Montreal to set up a congregation to help the poor. Over the next 100 years, the Sisters of Charity of Montreal, who were also called the Grey Nuns, became a major provider of social services and expanded westward into the prairies.

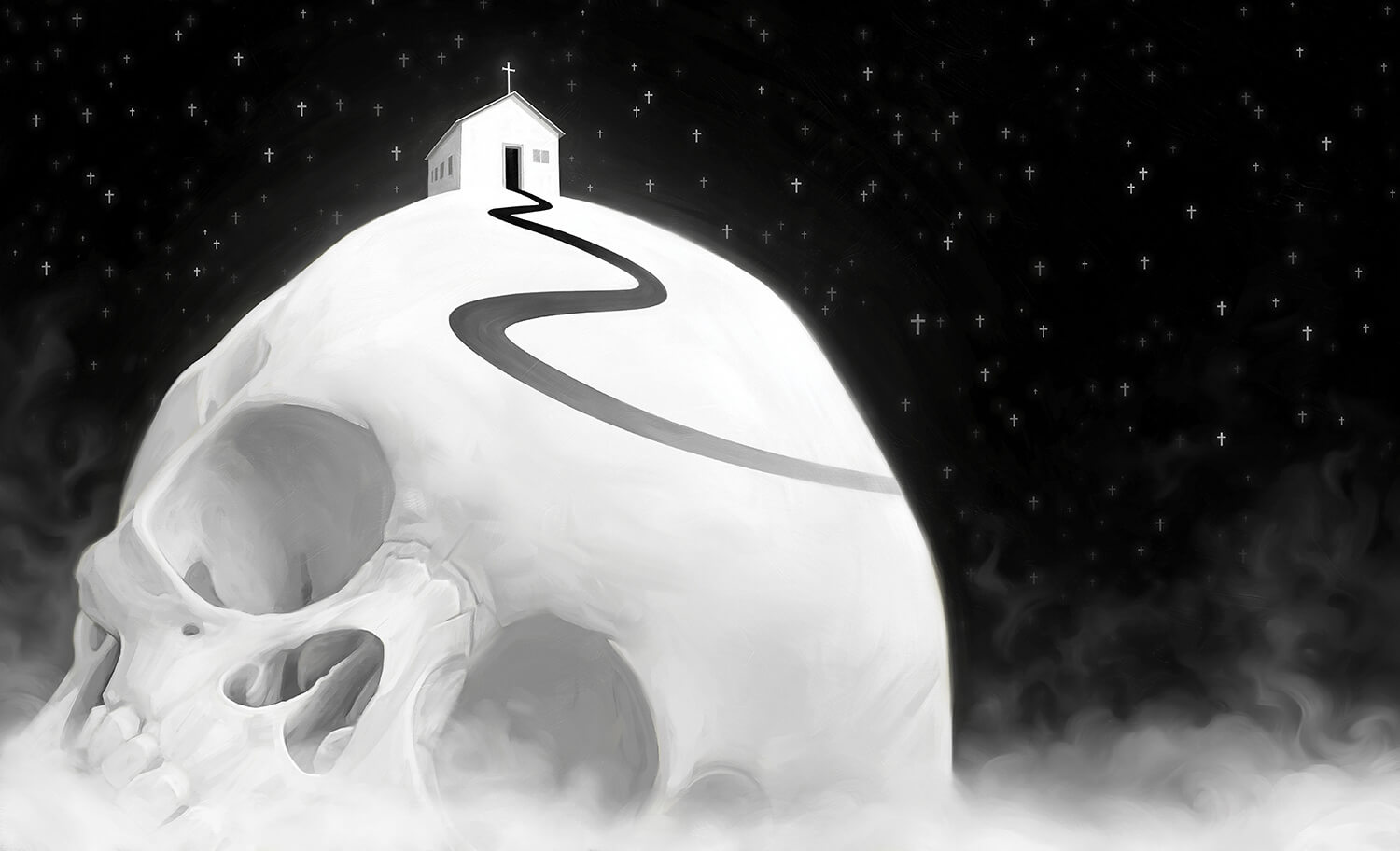

But, not mentioned along that same Founders Walk, the bitter legacy of residential schools, and the pain of the Indigenous children who were sent there.

The residential school in St. Albert was named for Marguerite d’Youville.

Today, as we start to reckon with the history of residential schools, there are often stark reminders in the forms of buildings and meadows. In the case of the Poundmaker’s Lodge in St. Albert, the land has been given back to Indigenous people and the facility is used as a healing centre.

But the number of potential similar graves, their precise locations, and the identities of those who may fill them remain largely a mystery at the site of St. Albert’s other residential school, the former Youville Residential School site. It was located on the east side of St. Albert, on what is now St. Vital Street between Mont Clare Place and Madonna Drive. This residential school grew out of a Roman Catholic mission school that was established for Métis children. It closed in 1948.

Kisha Supernant, who is the director of the Institute of Prairie and Indigenous Archeology at the University of Alberta, has been fielding calls from all over the country since the news broke in May of 215 bodies being discovered at a residential school site in Kamloops, B.C. She says the process of finding un-marked graves needs to be methodical and include the communities that may have youth buried there.