Nearly a decade ago, doctors discovered a benign tumour on Trevor Smith’s brain. He was told that it wasn’t serious, and it would be just fine as long as his head wasn’t subjected to a major impact.

On Sept. 26, 2012, Smith’s head was subjected to a major impact.

He went through the windshield of a pick-up truck that had collided with his motorbike, head-on. Smith was a broken man and, the fact that he survived is the stuff of reality TV. (In fact, he will be featured on Discovery Channel in the near future.)

The only reason he didn’t die soon after impact is that Devon’s fire chief was near the accident scene. Off-duty EMTs were also nearby. The chief called for the STARS air ambulance on his radio as soon as he saw the carnage. And he and the EMTs used bungee cords from trucks as tourniquets to stop Smith’s bleeding.

It would be easier to list which of Smith’s bones hadn’t been broken. His lung was punctured. His pelvis was smashed. And, to top it off, that impact activated the tumour that the doctors had told him he didn’t have to worry about.

As Smith began the arduous process of rehabbing his once-broken body, the tumour grew. Doctors warned it would soon give him headaches and then, eventually, impair his vision or even blind him completely.

And it was in a tricky spot behind the eyes that made it almost impossible to get at via traditional surgery.

Five years ago, David Lagimodiere began getting pain in his jaw. Shooting pain. Debilitating pain.

It hurt when he ate. The pain kept him up at night. Brushing his teeth was an exercise in agony.

“I could not sleep, I could not eat,” he recalls. “Every five seconds, I’d get a stabbing pain. And some nights I would go without any sleep at all. When I ate, it was like I was chewing on glass. I dreaded eating and I dreaded going to bed.”

He had to give up his job as a truck driver, something he’d done for more than four decades. It was too dangerous for him to be behind the wheel. He and his wife, Brenda, had no end to their suffering in sight.

Lagimodiere was diagnosed with Trigeminal Neuralgia, which carries the rather morbid nickname of the “suicide disease.” According to a 2018 article in the dentistry magazine, RDH, 25 per cent of TN sufferers succeed in their suicide attempts, double the American average.

Lagimodiere underwent brain surgery in attempt to stop his nerves from misfiring. The symptoms abated for a year, but then came back “with a vengeance.” He couldn’t be subjected to another traditional surgery because he had a heart stent put in and the doctors were concerned he couldn’t deal with the strain.

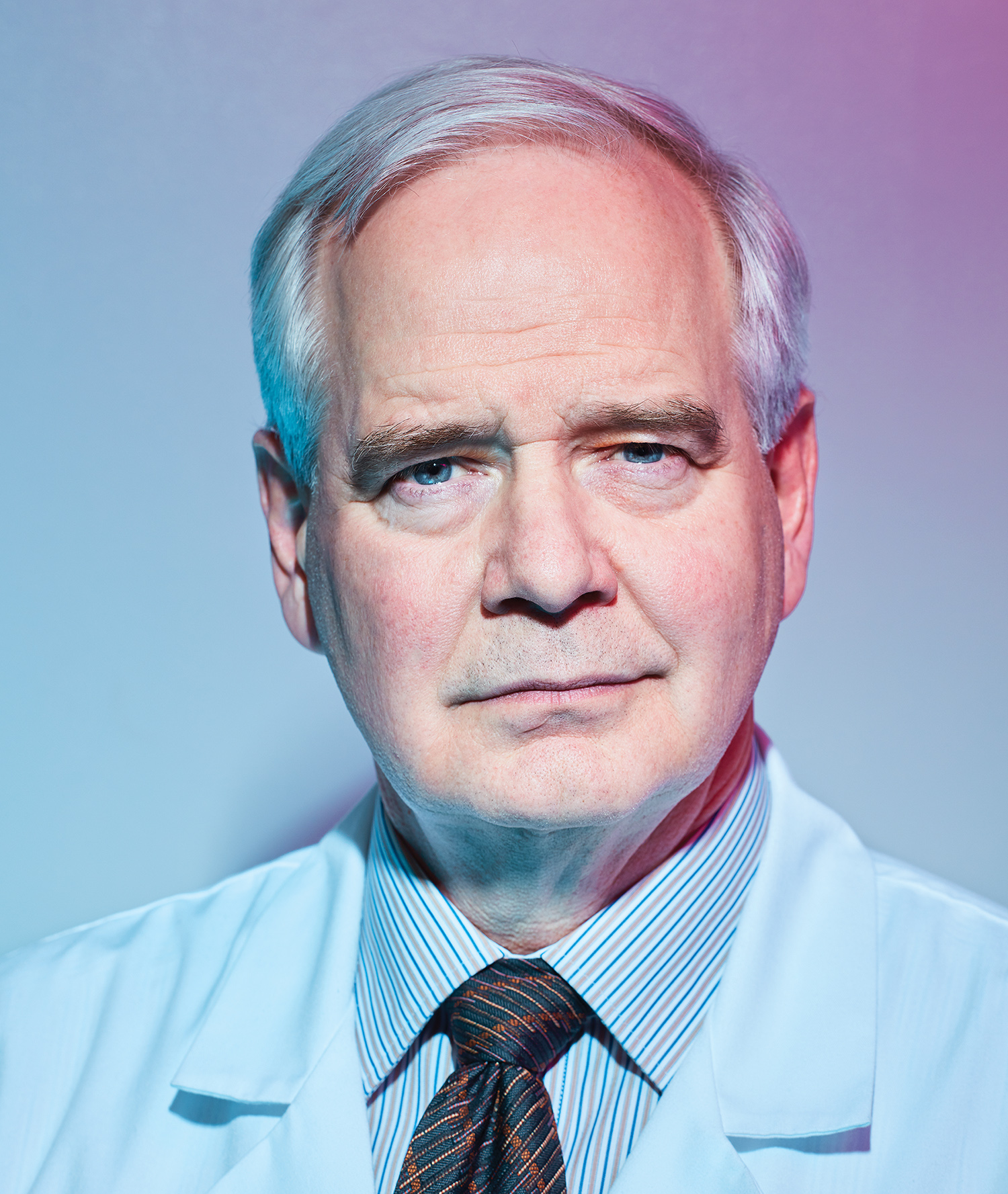

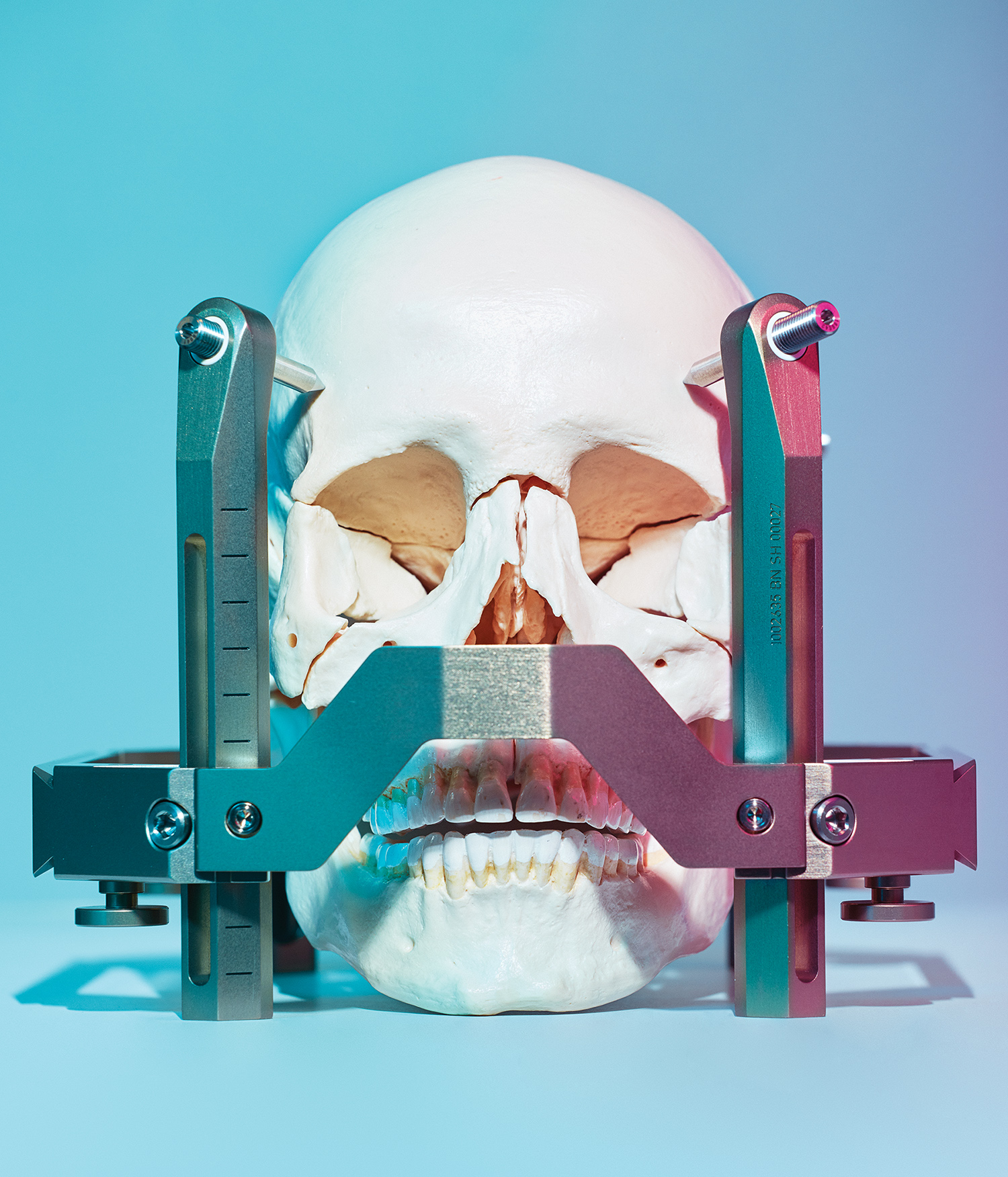

After the first attempt to relieve his symptoms failed, Lagimodiere’s doctors told him about the Gamma Knife, which was set to begin operations at the University of Alberta Hospital in late 2017. What is the Gamma Knife? It looks like a CT scanner. A patient has a crown bolted to his or her head — this is not nearly as bad as it sounds — in order to keep the surgical area stable. Then, the affected area is targeted using radiation. There is no drilling of the skull, no incision. It’s brain surgery out of a science-fiction movie. Except that it isn’t a science-fiction movie. Oh, and patients go home the same day. After brain surgery. Up until 2017, the only access Alberta patients had to a Gamma Knife was via a lottery. A small number of patients, fewer than 10, would get shuffled off to Winnipeg to be treated. According to Dr. Keith Aronyk, the Co-Director of the Gamma Knife Unit at the University Hospital, 304 patients have undergone over 400 procedures since the clinic opened.

“It’s revolutionized the way we treat a lot of brain conditions,” says Aronyk.

Many ailments are treated solely with the Gamma Knife. But, in cases where patients still need traditional brain surgery, the Gamma Knife can be used “to clean up the edges a little bit,” says Aronyk.

Imagine a patient with a brain tumour; a traditional surgeon might be able to cut out most of the tumour, but leaves a little behind to make sure the cuts don’t actually get too close to the brain itself. The little bits left behind can be subjected to the Gamma Knife.

The equipment is located in the new Scott and Brown Families Advanced Imaging & Gamma Knife Centre. Philanthropists Guy and Shelley Scott, and Jim and Sharon Brown provided a $3 million gift to help bring the technology to the University of Alberta.

The centre, located on the main floor of the University of Alberta hospital, looks like, well, any other sort of clinic you’d walk into. There’s a series of prep beds and offices, and the designers have disguised the fact that the $17.5 million facility is actually a vault — the Gamma Knife is surrounded by concrete walls, each 18 inches thick. Because the Knife is so heavy, it could not be placed in the upper floors of the hospital. The machine itself cost $5 million.

There’s a pedway directly over the clinic and a pedestrian tunnel nearby.

“It was an engineering marvel to get it in here,” says Aronyk. “Like threading a needle.”

And, on top of eliminating the need for incisions, stopping the risk of bleeding and infection, and making patients more at ease when they go in for brain procedure, it’s also got a pretty good hi-fi system.

“They put a crown on your head, it’s bolted on, and then you go in for 45 minutes, you listen to some relaxing music, and you’re done,” says Lagimodiere.

Trevor Smith has had a lot of surgeries. More than 40. Titanium rods have replaced his pulverized pelvis.

His hands, severed at the wrists during the accident, have been reattached. His easiest surgery? The brain surgery. As easy as getting your tonsils out. No, easier. He went in, had the frame attached to his head. That tumour that he was told would almost be impossible to get at via traditional surgery? Not a problem for the Gamma Knife’s virtual scalpel.

When his body was being slid into the machine, he was asked if he wanted to listen to some music. He thought he’d make a request for the smooth jazz and blues stylings of Etta James, because he was sure that a surgical suite would never have the music of Etta James on file.

He was told that the Gamma Knife suite had a library of more than 100,000 songs. Etta James’s music was available.

So, Smith listened to her music as he was having brain surgery done. He didn’t make it to the end of the album before falling asleep. And by the early afternoon, he was back at his home in Spruce Grove, eating soup.

Lagimodiere was one of the first patients to be treated with the Gamma Knife since it went into service in late 2017. Since then, he hasn’t had a severe pain attack. There have been times he’s felt tingling in his face, but he admits that the hardest thing right now is dealing with the dread that he might not be cured.

The doctors tell him that he can have one more Gamma Knife procedure, if necessary. So far, so good.

“I am still waiting for the big one to come, but I’ve got to get that out of my head, so the worrying doesn’t wreck my life,” he says.

Smith is riding a motorbike again. The first time he got on the bike, nearly 70 riders from the motorcycling community joined him for a group ride. It was an emotional moment; these friends helped his wife, Stacy, move into a new home when Trevor was in the hospital.

He’s philosophical about what medical technology has meant to him. Had this crash even happened a few years earlier, he wouldn’t have made it.

“Basically I am riding the technology wave,” he says. “But, really, if your life is in jeopardy, there’s no other place you’d want to be. I don’t know where I’d be without it. It’s a life-changer.”

With more than 400 procedures completed, the savings to the healthcare system are evident. Before the Gamma Knife, these would have been 400 surgeries that would have required extensive hospital stays. Beds would have been occupied. Families would need to take time off work to care for loved ones. Now, these patients go home immediately after their procedures.

“We did a business case and we found that this would save enough money to be worthwhile after three years,” says Aronyk.

Sometimes, you need to spend a bit up front to save a lot in the long run.

This article appears in the June 2019 issue of Avenue Edmonton