This summer, the Edmonton Police Service will turn on its newest tool for combating crime, the Operations and Intelligence Command Centre (OICC), a high-tech, multi-million dollar control centre in the Southwest Division location. When fully functional, four full-time teams of sergeants, constables and intelligence analysts will work 24/7, mining an ever-growing collection of public and private data with software and algorithms and distilling it all across a wall of 24 TV screens. It is, more or less, exactly what you’re thinking — which might mean you’re also thinking of Minority Report, or any other movie where police use technology to infringe the rights of law-abiding citizens.

That’s a reasonable concern, agrees inspector Warren Dreichel, who recognizes the pressure the EPS faces in making sure it gets it right. “We don’t want to be the agency responsible for screwing it up, because it’s really easy to set a bad precedent,” he says. Regulations exist to ensure the current, pre-OICC system follows privacy protocol, but Dreichel admits “hard limits (for the OICC) are still up in the air…Down the road, there’s a lot of work to do on privacy.”

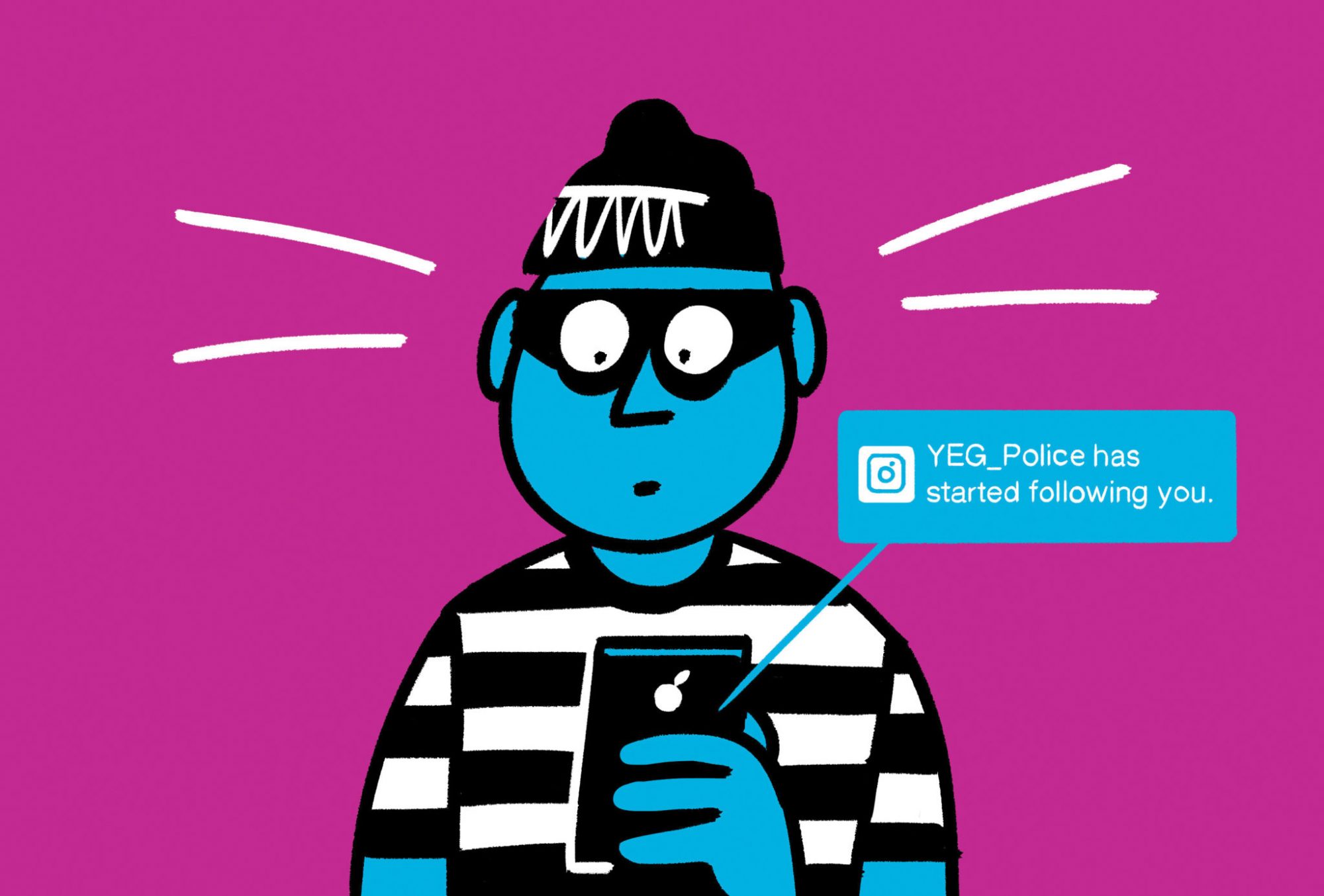

At its core, the OICC is just another response unit, like a patrol-car team, but it has the biggest brain. When a call comes in, it will search millions of records from databases that have long been accessible — past police reports, criminal and suspect profiles, and data from health services and the Canadian Police Information Centre. It filters the info faster than officers rushing to the scene ever could. But it will also access closed circuit security and traffic cameras, and social media feeds. Police must establish agreements ahead of time with businesses to access their security footage, but they are free to access traffic camera content and Twitter feeds, because you are too.

“When lots of people post, it can give us one more piece of the puzzle,” Dreichel says. An example: There’s a robbery at a convenience store, and somebody tweets a car is speeding from the scene. If that person’s phone’s GPS is turned on, the OICC’s mapping environment can pull it up along with all social media activity in the area, and filter by keywords. “We would then contact them and ask if they’re interested in talking with us. If they say no, we don’t push it. And we don’t access closed or private accounts,” Dreichel says. With images, police can only run them against their own mugshot database, not social media at large. “We’re not allowed and, responsibly, we shouldn’t,” Dreichel says.