Juan spent his life cut off from the world as a bus driver in western Cuba, but he knew where Edmonton was. At first, the reason was mysterious. Maybe he learned from other tourists, but set among palm-studded hills and tobacco fields four hours from the resorts of Varadero, the town of Viales wouldn’t see many Canadians.

Somehow, Juan had a map of Canada, and he unfolded it to show me my city. Then I understood: The resource was why he knew. His finger trailed northeast to Fort McMurray. “Hay mucho petrleo,” he said in a tone of awe and envy. “So much oil.”

To Juan, Edmonton seemed a Shangri-La of prosperity and independence. The oil sands impressed the 57-year-old in a way Alberta wishes it would the rest of the world, Canada included, especially if the dream of a national pipeline is to be realized.

This wasn’t Edmonton’s problem when oil hit nearly $150 a barrel in 2008, but today the bitumen bubble is both a killjoy and a motivator. There never was a plan to manage the oil sands boom, the late Ralph Klein admitted in 2006, so we’ve been in reactionary mode. Finally, however, there’s a will and a way – and a dire need, if we’re to maintain our prosperity and sense of independence – for the capital and oil sands regions to jointly address touchy subjects, namely roller-coaster markets and environmental impact.

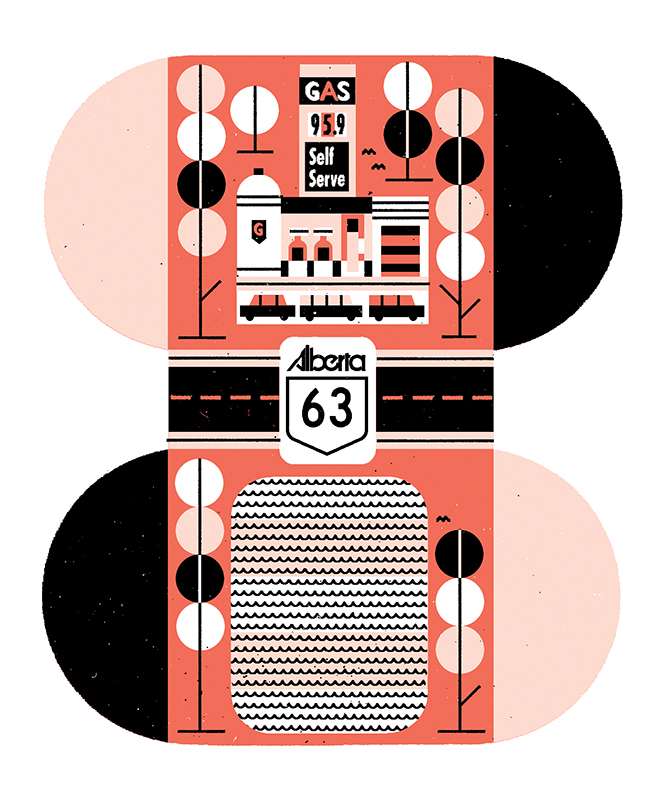

Reconsidering geography is step one, suggests Edmonton Economic Development Corporation President and CEO Brad Ferguson. “We have regional challenges and a regional reputation. We need to realize that we’re all part of one region and interdependent upon each other.” Highway 63 is a tie that binds, however dangerous and narrow it may be.

Some Edmontonians already know this oneness; for weeks on end they earn their livings in the oil sands before returning to rejuvenate with their families. On the flipside, Fort McMurray parents send kids here for diplomas and degrees. Industry sends bitumen to the Alberta Industrial Heartland, the processing hub on the northeast edge of Edmonton that employs 17,500 capital region workers and pumps $1 billion annually into the local economy. With the to-and-fro of people, oil and money, it’s hard to tell where one place ends and the other begins.