It’s a Friday night and all the seats are taken at a downtown walk-in clinic. People of all ages are lining up by the bank of windows overlooking Jasper Avenue, where they’ll stand for up to a few hours before being seated in a second room to wait a little longer.

Some of the patients likely have family doctors, but use walk-in clinics when they can’t make quick appointments; other patients might not have family physicians at all and instead have medical records strewn across the city at several walk-in clinics.

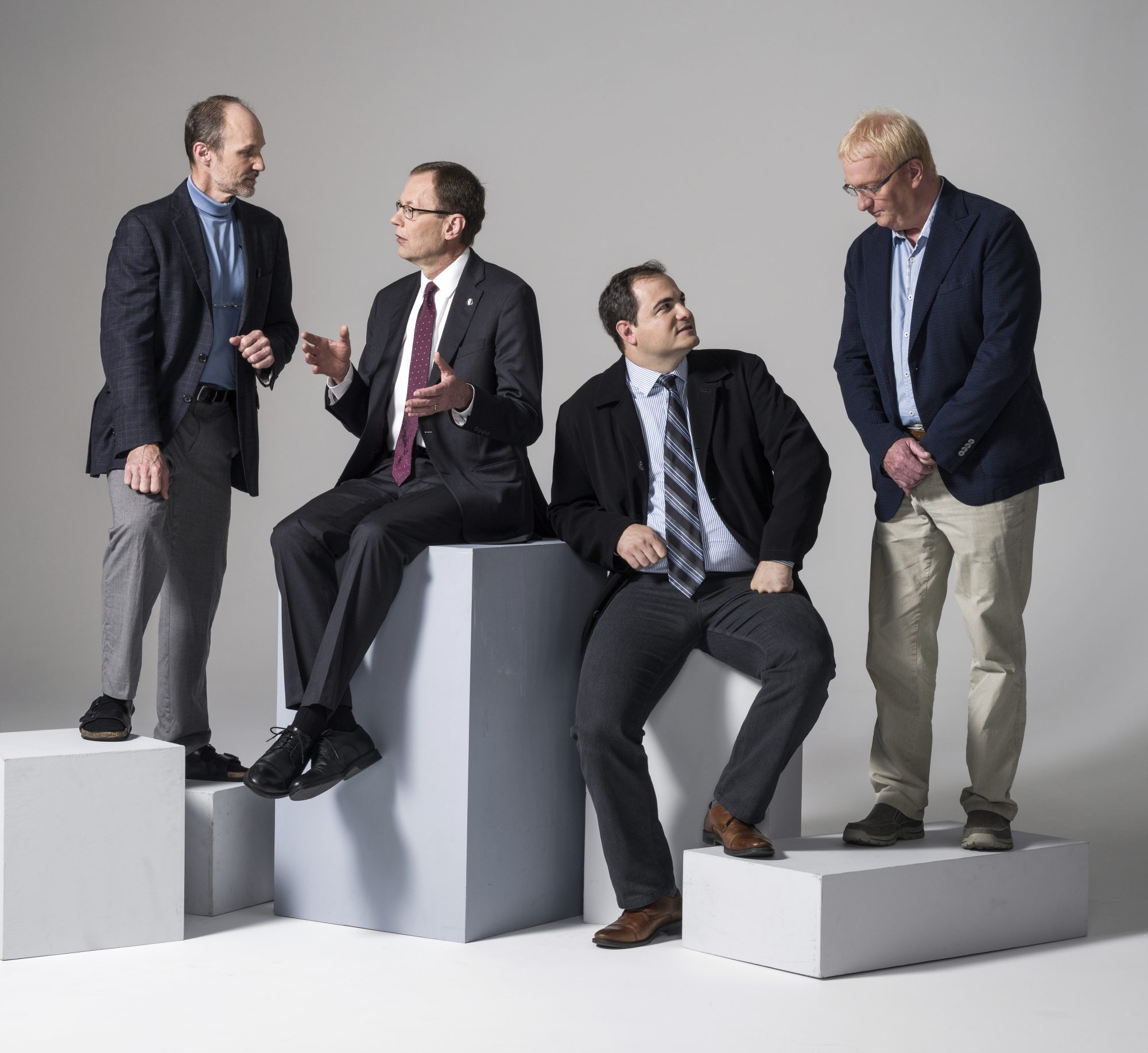

The wait lines seem to suggest the city is facing a family doctor shortage. But according to Dr. Carl Nohr, President of the Alberta Medical Association, we’re actually a little over the Canadian per-capita average for physicians in Alberta. A 2014 report by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) supports that idea — it says that after 2010, the number of doctors working in Alberta and Saskatchewan leapt by 20 per cent, the biggest increase in Canada. A newly released report from CIHI stated that there are 10,019 doctors working in Alberta as of 2015. But Nohr still believes there are shortages in specific specialties and geographic areas and says Alberta would greatly benefit from a physician resource plan to understand these deficiencies.

Meanwhile, Dr. Lee Green, a family physician and health services researcher, also questions the relevance of looking at these statistics. In the past, those numbers have failed us, says Green. In 1991, the Federal/Provincial Advisory Committee on Health Human Resources commissioned the Barer-Stoddart Report as a means of determining how to move forward with health care. The report proposed over 50 changes to the medical field—some that had merit, but were, unfortunately, says Green, ignored — and others that said Canada was headed for a surplus of physicians, which were embraced. As a result, fewer enrolments were accepted in medical schools, and less postgraduate training positions were offered.

But those statistics, says Green, were based on faulty assumptions. “They were looking at data from the old days when family doctors were 45-year-old males who worked 100 hours per week and had no life. No one wants to live like that anymore,” says Green.

And while doctors are changing the number of hours they work, technological advances are changing the way they work. In the past, says Green, if someone had a heart attack, very little could be done — but now advancements mean more follow-up, and more time and resources needed to deal with the patients. Progress results in more health care options, and thus, more work and the need for more doctors to cover the same population.

But just adding more doctors to the mix isn’t the best solution either, says Green. Efficiency and proactive health care comes through teamwork, which is the reasoning behind Primary Care Networks (PCN), which are not-for-profit corporations formed by physicians within an area who work with a board to provide education and support to patients.

There are now four Primary Care Networks in Edmonton, and several in outlying communities — nine altogether — which have been developed over the last 11 years. The idea is that health care professionals including doctors, nurses, dieticians, exercise specialists, and psychologists, for example, work together on overall health rather than just addressing health problems as they arise, says Justin Balko, a physician and Primary Care Networks Edmonton Area Lead. Each PCN is a little different and tailored to its community needs with potential for exercise programs or mental health services or programs for the elderly.

The goal is to move towards a Patient Centre Medical Home (PCMH) model, which means continuing to add more proactive supports, lessening wait times, and coordinating care across the health care system, all while ensuring a patient-centred focus.

“Gone are the days of the doctor being head of the kingdom,” says Balko. “It’s about putting the patient first. It’s about realizing it’s not just about medications and seeing your doctor — it’s about your social supports, your community engagement, and access to parks, playgrounds and feeling safer in your community.”

But Green believes, there’s still a long way to go. . Most health care centres and hospitals in the city operate on a fee-for-service model, which means that doctors are paid for each service they conduct on a patient.

That means, says Green, doctors aren’t rewarded for spending time on patients. Instead, the system’s set up to reward those who see as many patients as possible in as little time as possible. As a result, patients with multiple health problems and issues can fall between the cracks.

With a PCN, doctors are still paid by fee-for-service, but the networks receive extra fees each month for wrap-around supports — such as having chronic disease management nurses, psychologists or dieticians to help patients with over-all health.

There is also still a disconnect between primary care and some specialties, resulting in huge wait times for specialized care, says Ernst Schuster, a doctor who’s been practicing family medicine for 31 years. “I pray every morning that I don’t have to send a patient to a urologist or an orthopedic surgeon,” he says. “Because I know I’ll have to work especially hard to figure out a way to get that need met.”

Someone with a blown out knee who couldn’t walk might have to wait eight months to see a surgeon and another six to get into the operating room, he says. Someone with signs of colon cancer might need to wait up to a year for a colonoscopy.

“It’s totally unacceptable,” Schuster says.

Justin Balko says that PCNs are working to reduce wait times. Screening for colon cancer is especially a priority. He recognizes there is a dire need for this specific screening and his team have doubled the number of screening slots available within a year. But it’s something that needs to be ongoing — and he believes they can continue to improve numbers.

“There’s sometimes a divide between the needs of our specialist colleagues and their schedules and primary health care,” he says. “It’s a lot of communication between physicians and specialists; and it’s a shifting of resources and time and effort by all people involved.” His team gathers information about what resources are available at hospitals and can more effectively determine when more people need to be hired.

Green says it’s a move in the right direction. Before coming to Alberta, Green worked on a team that published the largest group of studies of the Patient Centre Medical Home (PCMH) model to date — it involved 2,400 practises around Michigan.

PCMHs operate within the framework of a team. They keep a registry of patients with chronic diseases, and a nurse will go through that list every week. “That way they can see who needs updates for important services that will keep them healthy. It’s a very proactive style of management — a lot of work is done outside of regular doctor visits,” says Green. There is a lot of follow-up with patients, and ideally, problems are caught early.

While a PCMH could operate on a fee-for-service model, it requires an update on what activities are considered services — emails, telephone calls and team meetings with panels, for example, make up important parts of treatment. Currently, some uses of technology aren’t legal or billable in our province.

But Green believes ultimately it would be best to go to a salary or capitation type model that isn’t related to visits. And Alberta Health Minister Sarah Hoffman agrees; at the beginning of this year, she said she believes it would be best if doctors eventually abandoned fee-for-service in favour of other models.

According to CIHI, Alberta doctors are the highest-paid in Canada; its 2015 report said the average gross annual payments to physicians were $366,000 per doctor in this province, nearly $30,000 higher than the national average.

“If you want to do health care right, you have to get away from paying for piecework and, instead, pay for results,” Green explains.

The results in Michigan were impressive—family doctors could take care of more patients, get better patient outcomes, fewer emergency visits, all at a lower cost of care. And Green says the Alberta Health Ministry is interested in supporting PCNs and transitioning to more of PCMH model. The fact that it was successfully done in Michigan is good news for Alberta because the two places are similar.

“In Michigan, it was done in groups called Physician Organizations, which are a lot like PCNs so the pieces are there to do it in Alberta. They are scattered all across the state, everywhere from the inner city of Detroit to the wilds of the upper peninsula of Michigan, which is as rural as anything you’d find in Wood Buffalo,” he says.

Community Health

Dr. Francesco Mosaico walks through the hallways of the Boyle McCauley Health Centre, smiling and greeting everyone he passes, from patients to nurses. The facility has been in operation since the 1970s, and yet ironically represents what physicians and health care professionals like Green see as a more progressive — or at the least a more effective — way of providing health care.

Mosaico makes an hourly wage and works alongside a team of professionals who treat vulnerable populations prevalent in the area including homeless individuals and those with addictions. Nurses handle more tasks than they typically would in a fee-for-service type of situation, and many services are under one roof—addictions services, an x-ray lab, needle exchange and a dentist’s office, for example. Off-site health services are available at various facilities, as well as services to help people find housing. It’s not part of a PCMH, but it’s a community health care centre, which has similar elements.

A patient’s first time at the health centre might involve an hour long appointment whereby the nurse or doctor will determine the issues that are creating problems for the person’s well-being — and, after that, each appointment will be at least 20 minutes long.

The health care centre is a boon to the inner city, a place where doctors in regular clinics are difficult to find. “If you go to less-privileged areas, there is definitely a higher need for more doctors,” says Schuster. The problem, he says, is that the fee-for-service system makes it very tough to provide the kind of proactive, multi-level support needed by people who are struggling with complex issues related to poverty or addiction. As a result, some doctors may avoid going to these areas, creating even more of a deficit.

Even if someone from the inner city, who was homeless or had an addiction, were able to find a family doctor — and managed to get transportation to the appointment, make it there, show appropriate ID, and not feel intimidated — that person would generally only be able to discuss one issue at a time.

“Where would you begin?” asks Cecelia Blasetti, executive director of the Boyle McCauley Health Centre. “Because even if you say, ‘OK, let’s talk about your diabetes,’ how can you not address the fact they have no place to live and no place to keep their medication?” Blasetti says care at the centre is about the whole patient, and ensuring that person’s wellbeing is addressed alongside his or her physical health.

Just down the hallway, Kong Deng is sitting on the crinkled paper of an examination bed, waiting for his monthly appointment. His smile stretches wide as he shakes Dr. Mosaico’s hand. Deng’s wearing a red cap, and Mosaico offers him a green one instead. There’s been a lot of activity — a gang known for wearing red bandanas — in the area, Mosaico explains, and he doesn’t want Deng to be mistakenly associated in any way.

Ever since he lost his leg several years ago, Deng’s been a regular at the Boyle McCauley Health Centre. At just 13 years old, he began fighting in Sudan’s second civil war. But that’s not where his leg was lost. After the war ended in 2005, the Red Cross sent him to Canada where he promptly fell through the cracks of the health-care system. While homeless, a night’s sleep in frigid temperatures caused severe frostbite that eventually led to the amputation.

Deng was facing emotional and mental trauma that was invisible while struggling with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. He was taken to a hospital, but Deng was adamant that he did not want an amputation, and was labelled as hostile before being referred to the Boyle McCauley Health Centre.

“When I first came to Canada, no one would talk to me, now everyone— the doctors, the nurses—would say, ‘Hey, come here.’ They came to visit me in the hospital. They even brought me books,” says Deng. Mosaico says Deng responded immediately to the compassion of the health care staff.

That level of compassion, says Green, is difficult to cultivate in a fee-for-service model because there just isn’t time to understand a patient’s story in a holistic way. At Boyle McCauley, the focus is placed on what works best for the patient. It’s the type of system that is obviously well set up for those who are struggling with multiple issues but it would really benefit anyone, says Schuster.

“A lot of regular clinics are just set up to deal with burning fires and then just sort of put them out and you know what’s missing is the continuity, the attachment, the relationship building, stabilization, preventative care, good chronic disease management, which we all know is very important if you want to reduce emergency visits and get better care,” says Schuster.