Tess (name has been changed) is sitting at the front of the room, perched on the edge of a chair while watching a short film. Her hands are shaking, her eyes wide, and she winces and covers her mouth at the scariest moments.

She shifts uncomfortably, suddenly grabbing the sides of the chair as though she might try to flee. Someone asks her if she wants to continue and she nods quickly before shifting her grip to the table in front of her.

Four women seated behind her suddenly gasp in unison. “Oh, that was a bad one,” Tess says, eliciting nervous laughter from the room.

The group have gathered for Fright Night, but they’re not here to watch the latest horror film; instead, they’re facing their fears through an exposure therapy program developed by psychologists Janet Caryk, Wes Miller and Joti Brar-Josan. It’s an opportunity for clients of the Centre for Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), who are already extensively addressing their phobias and anxieties through regular one-on-one sessions, to gather in a group and gradually expose themselves to things they would normally avoid.

For Tess, that means watching a series of very minor car crashes on Caryk’s computer screen. Each fender bender elicits a flinch from the young woman, but it’s a slightly more substantial side-swipe that generates the collective fear in the room.

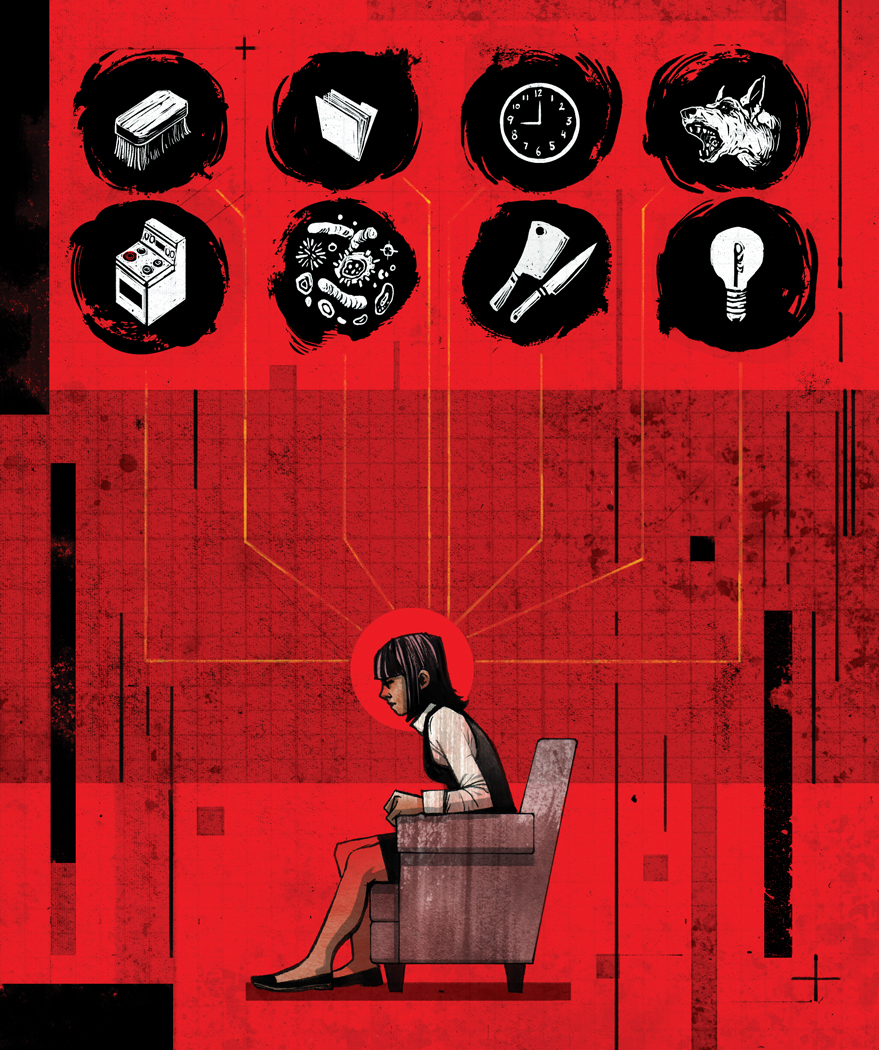

Fright Nights are for people with anxieties and fears of all kinds – some have generalized anxiety, others suffer from Phobic Avoidance Disorder, which can lead to the avoidance of social situations or something as commonplace as flying. But, on this day, Tess, along with the four other women sitting behind her, all have Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), which means that they have unwanted, repetitive thoughts that are generally only calmed through compulsive behaviours.

Currently, Tess is fearful of driving – but she has been working on overcoming it for months. She’s been working with a therapist at the centre who has helped her reframe thoughts through CBT. She’s already completed driver’s training and plans to take more classes before going for her licence.

And now, watching a video with minor accidents helps her to accept that there is risk involved in driving, but that she can handle it, even if something happens beyond her control. Individuals with OCD want to be constantly sure of their safety – they conduct elaborate rituals to try to feel as though they have some control over their environment.

“If I have to go through the driver’s ed program in more incremental steps, and pay more money, so be it,” says Tess. “That’s not the issue. Not killing someone is the issue.”

Caryk explains that OCD often plays to our worst fears – and those with the disorder have thoughts that say they’re better off just avoiding the activity altogether. “But,” she says to Tess, “you’re saying: ‘No, I’m willing to take the same risks as other people. I’m fighting back, and taking driver’s training.'”

We all have an enormous amount of thoughts swirling through our heads in a day – anywhere between 40,000 and 60,000 – and all of us have thoughts that are similar to someone with OCD. We may worry about whether we left the iron on; whether our child will be in a car accident; how we came across in a meeting. The thoughts themselves aren’t the problem; it’s the way someone with OCD interprets them. For them, these ideas take on importance and significance – thinking that you may get in a car crash or accidentally hurt someone else suddenly feels like a prophecy that needs to be avoided at all cost.

In the past, people believed it was best to simply avoid any kind of negative or anxious thoughts. If people felt anxious, they were told to snap elastic bands on their wrists to distract themselves. But an uneasy thought is like the elephant in the room – the more you ignore it, the more you think about it. And next time, maybe it’ll have grown into an impossible-to-ignore woolly mammoth. Now, psychologists urge people to face those thoughts, even egg them on.

Caryk passes around a sheet full of lines that her patients live by, which include: “Don’t fight it, invite it. Practice being afraid; I want this feeling. Embrace uncertainty. It’s OK for me to be afraid, I can handle this.” The specifics of the thoughts and the severity are different for all, but the underlying need for certainty is the same. Compulsive behaviours – cleaning, organizing, and counting – along with avoidance of anxiety triggers, can create a temporary calm but over time these reactions perpetuate the disorder.

Breaking the cycle means facing the fears, according to Caryk, who adds that she and her colleagues started offering Fright Nights as a bonus side-treatment to clients two years ago. They had done meet-and-greets in the past where they matched up clients with similar phobias. These meetings were huge successes and led to the idea for Fright Night.

Tess smiles broadly after finishing her exposure. She takes a seat, explaining her anxiety has plagued her since the age of 12, when she began restricting her diet and conducting obsessive food rituals.

She’s a university student, tutors other students and works as a server in the hospitality industry – her anxiety is at a low level today. But her backstory belies fears that grew so severe she became house-bound for about three weeks in the winter, fearing someone would break into her home. She came to the centre shortly afterwards, and things have been improving since.

Fright Night, she says, has been the most rewarding part of her therapy – it’s the one place where she feels normal and understood. Both Caryk and Miller allow the clients to determine what exposures are best for their level of anxiety on that night. And then they will often take clients out onto Jasper Avenue, just a few flights below their office where they conduct anti-shame exercises, which are particularly effective to those with social anxieties.

Many of the phobias that they address at Fright Night stem from a fear of judgement – something as simple as dropping change while ordering a coffee could make some clients frozen with fear. So, one technique is for Miller and Brar-Josan to do the unimaginable – they’ll do all the things their clients are too embarrassed to try. Brar-Josan has dressed up in crazy hats and glasses while shopping and waved at passing cars while Miller has lied down on the sidewalk and asked for spare change from passersby. Once, he went with clients into a grocery store, put water from the vegetable spritzer all over his face, and went to buy something at the till, appearing nervous and sweaty.

“They learn vicariously by observing the response – it’s innocuous. Even if it is judgemental; who cares? The clients learn that if that happens, they can handle it,” says Miller.

A clients ready to tackle the next stage of his or her phobia will then be in the hot seat – wearing the crazy glasses or ordering the coffee with just pocket change. The exposure gradually gets a little more intense and increases anxiety levels.

“We’re having some fun talking about all the fun things we do, but these clients are really feeling it. It’s not like this is easy; some are even crying. They are getting better, but it’s impactful to experience this,” says Miller. Treatment plans are specially designed for each client, depending on their anxieties, and their goals – but typically 8-12 sessions will give clients the skills needed to improve functioning.