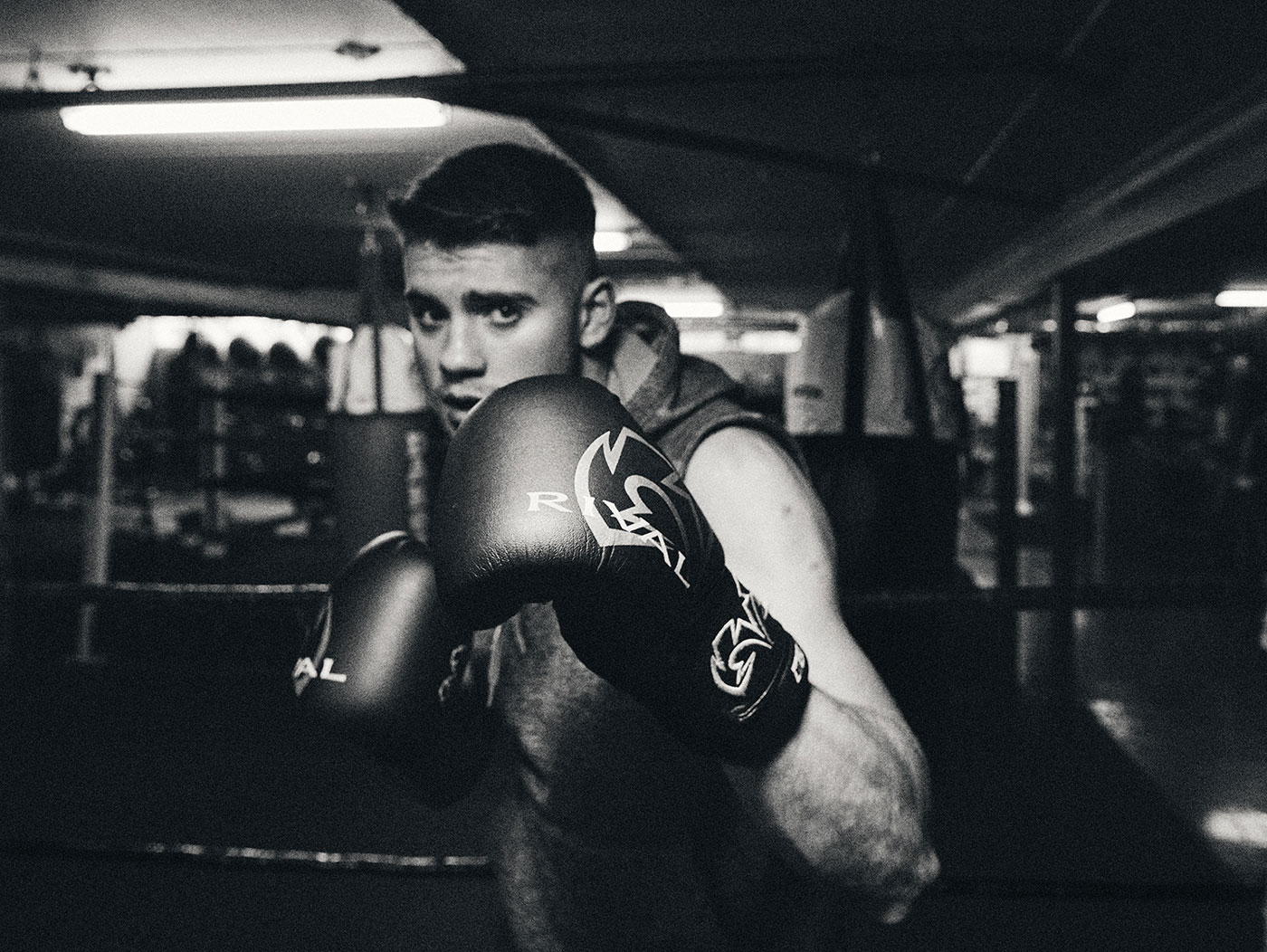

Photos by Colin Way

Left jab, right cross, slip left, left jab, right cross. Left jab, left jab, pivot and turn, left jab, right cross.

And so it goes. We stand in front of the large wall of mirrors at Edmonton’s Panther Gym, the sweat already starting to soak through our shirts. In front of us is Benjamin Alvarez, calling out punch combinations. “Jab! Cross! Slip! Jab! Again!” We copy his combinations, taped-up hands flying through the air, punching at imaginary targets.

We put on our boxing gloves and walk towards the heavy bags. They hang from the low ceiling like carcasses in a meat locker. “Up! Up!” Alvarez calls, and we descend on the bags like predators. Left, right. Jabs. Then deep, cutting hooks, imagining that we’re pounding someone in the rib cage. Then uppercuts. If only there was a jaw where the glove makes contact with the bag.

After eight minutes of straight punching, Alvarez asks me if my shoulders are on fire.

It’s hard to tell, because I can’t really lift my arms at all.

“Good, because if they’re not on fire then I’d make you do it again,” he says.

The sun has yet to come up this spring morning, but here I am, at a gym located underneath a vet clinic, working out with a small group of guys being shepherded by Alvarez, who isn’t just any old trainer. Alvarez is a four-time provincial boxing champion; but, at the moment, he’s an example of what we see all too often with Canadian athletes who aren’t hockey players — they are more recognized internationally than they are at home.

A week after my training session with Alvarez, the Edmonton-raised fighter heads to California to train and hopefully catch the eye of middleweight champion Canelo Alvarez. According to Forbes, Canelo Alvarez is the world’s highest-paid athlete, with a contract that will pay him a minimum of US$365 million over 11 bouts.

But, while Canelo basks in fame and cash, Benjamin’s trip to get to Chula Vista, Cal. was subsidized by a group of passionate backers. And this goes back to why he spends Thursday mornings training a small group of Edmonton businessmen.

It’s a symbiotic relationship. Benjamin believes he can be a successful pro. He believes in himself. Problem is, it’s not easy for a Canadian boxer to get the kind of funding needed to train. And that’s where these members of the business community stepped in, led by Top 40 Under 40 alumnus Jared Smith of the Luxus Group. They’ve been helping Alvarez make trips to places like California and the Mecca of boxing, Las Vegas, so he can train and get better. They’ve been helping pay for the support staff a boxer needs.

The visit to California goes better than Benjamin can dream. He goes to the famous House of Boxing, and impresses famed trainer Carlos Barragan. In fact, the sessions go so well that Barragan agrees to take Benjamin to Canelo’s secret training facility, where he gets the chance to shake hands with the world’s top-earning athlete — and also get himself in front of Canelo’s management team.

Benjamin is invited to return to California in a month — and, now, his goal is simple; to impress the Golden Boy promotions team, and be signed to their camp. If this happens, Barragan will become his full-time trainer.

“They have great plans to groom fighters,” says Benjamin. “They can put you in front of fighters who you can build your record up against, and get the knockouts you need to get onto the radar. The thing about boxing is the zero. That is, once you turn pro, what people care about is if you have zero losses. The second you lose, everything changes because there is no mystery anymore.” Alvarez came to Canada from Chile when he was 11. His father had just lost his job in the Chilean port city of San Antonio. An uncle, already in Canada, sponsored the Alvarez family, which included Benjamin’s mother, two brothers and a sister, to make the move.

But Alvarez recalls that, when he came to Edmonton, it wasn’t easy. He was larger than average, which meant all of the tough kids wanted to measure up against him. He didn’t speak English, so he got made fun of for that. And the after-school fights at J.J. Bowlen became pretty regular occurrences.

“I was bullied a lot,” Alvarez recalls. “I was strong and tall, so I was targeted.”

Then, after a fight in which Alvarez admits “I got my ass kicked for 10 minutes straight,” the kid who just administered the beat-down told his victim about boxing classes. So, Alvazez, at age 12, went to the Panther Gym to learn how to defend himself.

“I fell in love,” says Alvarez. “The smell. The atmosphere. The competitiveness of it all. And I guess the rest is history. Boxing, for me, is a way to escape the normal way of life. Nothing interests me as much as fighting does.”

He was soon sparring with kids much older than him, and his career path was set. And it was here that he caught the eye of trainer Benny “The Jet” Swanson. For a decade, Swanson has worked with Alvarez.

Alvarez suffered a setback at the recent provincial championships, where he lost a split decision at the Leduc Recreation Centre in a fight that, to the naked eye, he looked like he’d won. But, if there’s one issue that continues to dog the sport of boxing, more so than the violence of the sport itself, it’s the way that judging is still shrouded in mystery. Alvarez notes that a lot of amateur-fight judges have never been inside the ropes. A rematch was scheduled and then called off. But Alvarez was later invited to participate in Canada’s boxing nationals, where he took the bronze medal.

Alvarez’s amateur record — four provincial titles and a chance to represent Canada at a recent tournament in Mexico — is excellent. There had been plans to go for the 2020 Olympics, but the sport’s future is in doubt when it comes to the Olympic movement. After a string of controversial decisions and allegations of fight fixing at the 2016 Games, every judge who worked in Rio was suspended. And, currently, the sport’s status as an Olympic event is being reviewed.

That’s why he’s already been sowing the seeds for a pro career. Before he went to California, Alvarez went to Las Vegas to train at the gym that’s the base for boxing legend Floyd Mayweather and his cadre of fighters. He sparred world number-six-ranked fighter Andrew “The Beast” Tabiti. Trainers joked that they should be

charging $20 admission fees to see the two fighters spar. He said he was offered the chance to remain in Vegas, but that the circumstances weren’t right. After the successes of his recent American visits, he knows that remaining an amateur isn’t for him. He wants to go pro as quickly as possible. The Olympics are officially off the table.

“The Olympics was at one time his best path,” says Smith. “That has changed now though as a result of traction with the Canelo and Mayweather gyms.”

And he knows that, despite the fact he has his own trade, Flow Electrical Contractors, established in Edmonton, he will one day need to leave. Right now, he’s earning money through his electrical work to subsidize his training trips to the United States.

“I need better competition. No one in Alberta wants to fight me. I’m the top dog. I don’t think I’m a nice guy. I’ve got such a big ego. Some people think ego is a bad thing, but I have the ego to believe that I can win.”

And, thanks to his benefactors, he has access to top trainers and medical services.

“They motivate me,” Alvarez says of Smith and co. “I look at how they dress, what they’re driving.” And, in return, he helps them train — and learn about the dedication needed to be a fighter.

And, maybe, one day, they’ll be in front row at Caesar’s Palace, as Alvarez fights for a belt. Maybe they should already be thinking about the entrance music.

But, for now, the Edmonton fighter has a lot of people to impress. He can’t simply be that kid from Canada. He has to establish himself in a part of the world where boxing is a massive part of the sports culture.

“I have got to do this. I’ve got to turn pro. If I don’t do it, the last 10 years of my life will feel like they have been a lie. Honestly, my parents were not 100 per cent supportive of my move into boxing; like all immigrant parents, they live for their children. They wanted me to go to school. They say that you don’t just do it for yourself, you do it for other people. I want to prove to my mom and dad that boxing is the right thing. I want to prove to Benny that he didn’t waste his time with me.”

This article appears in the August 2019 issue of Avenue Edmonton