Hestands a foot away from me, staring intently in to my eyes. His hair is long and snowy white, draping wildly to his shoulders and blending into his nearly bushy beard of the same shade. Every time I smile, so does he, revealing deep laugh-lines and crevices under the veil of facial hair. I raise an eyebrow; he raises his. My head turns to the left; his follows.

Briefly breaking eye contact, I scan across the room. Six long tables are pushed against the walls to accommodate the scene unfolding at the centre of the space. My reflection and I are not alone. Seven pairs of Santa Clauses mirror each other’s movements.

My partner and I lock eyes again and I catch my reflection in the glasses that sit delicately at the tip of his nose: Short, dark brown hair, a close-trimmed black beard, laugh-lines nowhere near as pronounced, and a body at least 80 pounds underweight. While I’m still not sure what improv training exercises have to do with becoming a gift-giving North Poler, what’s even more uncertain is whether I’ll even graduate from the Victor Nevada Santa School.

It’s only one of its kind in Canada and recognized by some of North America’s top Santas. Since 1998, professional and aspiring Santas have enrolled at Santa School to master the art of becoming St. Nick, and get hired for commercials, malls, parades and events anywhere from Chetwynd to China, or – as is more likely in my case – from house parties to West Edmonton Mall. But first, they must past muster with the dean of the Calgary-based school, Jennifer Andrews, also known as “Auntie Claus.”

The school’s founder is Saskatchewan-born Santa Claus Hall-of-Famer Victor Nevada (John Hubenig), whom the Globe and Mail once named Canada’s Top Santa Claus and who literally wrote the book (or one of them, anyway) on being Santa. His opus, All About Being Santa: The Manual of Bringing Joy, is still used as a training manual at the school and, on his deathbed in 2009, he left the school to Andrews. (Talk about a gift from Santa.) Now it’s up to her to instruct grown men on how to properly dye, bleach and maintain their beards, and other more basic hygiene practises. She teaches photo poses and proper use of “ho ho ho.” Over the course of three days, 17 men from across Canada and the United States and three aspiring Mrs. Clauses are readied to walk, talk and act like what Andrews calls a “Santa Regional Representative.” In other words: someone who can fill in when the “real” Santa can’t be there.

Halfway through the first day, I’ve yet to spot “the real Santa,” but there are some close approximations. There’s Santa Kelly, a long-time Kris Kringle returning for professional development, who is thinner than the others. Or Santa Brian, who makes up in belly what he lacks in height, and wears a stretched Hawaiian T-shirt patterned with Christmas trees, holly and mistletoe instead of palm trees and pineapples. Then, Santa Bob Slocombe comes into view – the whole view, as he mimics my every gesture and expression.

At six-foot-four and speaking with a booming voice, his sheer presence makes me feel like a child. His beard is impeccable. The tip of his nose, round and red as a ball, is reminiscent of an old Coca-Cola Christmas ad. In a shirt, jeans and leather work boots, he resembles Santa on a day off. But he has little to say, which kills the illusion and leaves me wondering what’s behind the beard – all the beards in the room. After all, just what kind of man wants to surround himself with whiney, fidgeting, stinky kids for three weeks a year?

It has been 24 years since I believed in Santa Claus, since my heart was captivated by the wonder of the man. My mother, overjoyed to share the Christmas spirit with her firstborn, was quick to instill the Christmas spirit before my eyes could even focus. It’s impossible to remember our first meeting with him at Red Deer’s Bower Place mall, but it’s well documented in my family photo album – as are seven other encounters over the next seven years. Every last one of them was with an imposter.

One Santa’s eyes were green. Another’s were brown. There was a mix of real beards, fake beards, scraggly beards and bushy beards. The only constant was my smiling face – believing, without question, that this guy was the real deal.

And clueless to the fact that my mom plopped me into a strange and totally ordinary man’s lap.

Who were these guys who hold such odd prominence in our photo albums, our childhood memories, our psyches? In any other circumstance, children are taught to be wary of old men who want to work with kids.

It’s an unfortunate stereotype and product of the times, but just about everyone has given it a thought as we freely pass our children off to the remarkably convincing bearded strangers at the mall, wave to them at the city parade or watch the less-than-convincing Kris Kringles sneak back a shot at the office holiday party.

“That’s why the good Santas are trained,” says professional Santa Carlo Klemm. “And, in most cases, we’re required to do mandatory police background checks before we’re given a job.”

I prepared for class a week ahead by calling Klemm (a.k.a. Santa Edson), one of Edmonton’s most famous St. Nicks. You may know him from Santa’s Parade of Lights, held, for the first time outdoors, downtown on Nov. 21, but he has been a staple at local corporate parties and special events around the city, in St. Albert and at Fort Edmonton Park for years now.

When it comes to the “Bad Santa” stereotype, Klemm is quick to set the record straight. “Yeah, sometimes there’s the Santas who maybe take a drink while on the job, or let kids see them smoking in their costume,” he admits. “But those aren’t real Santa Clauses.” He should know the difference. Since becoming a “Santa Ambassador” in 2007, Klemm has also become a self-proclaimed “worldwide Santa community-builder.” He runs at least three private Facebook groups that connect St. Nicks from across the globe and is an alumnus of three Santa schools across the continent, including the Victor Nevada Santa School in 2009. He spent a portion of his 15 years as a town councillor in Edson, advocating for it to become Canada’s only year-round Christmas community. “The town of Edson and its business leaders didn’t like the idea of walking around wearing red suits and pointed ears,” says Klemm. “But, from then on, I had the Christmas bug.”

Klemm was elated to learn I’d enrolled in Santa School and had a few tips that went beyond properly cleaning one’s boots and shopping for good sleigh bells.

Believe it or not, there are two classes of Santas: Real-bearded Santas and “traditional-bearded” (or fake-bearded) Santas, and they are often at odds. “Some guys will tell you can’t be a real Santa without the real beard,” says Klemm, who is in the latter camp. “But there are some high-quality beards out there, and you have to take care of them as you would your own hair.” And prepare yourself for dubious children set on testing not just your beard but your entire performance.

But his most valuable lesson was that I need to be prepared for emotionally distraught children who look to Santa as a genuine hero. “A lot of us old guys can put on a beard and say ‘Ho ho ho,'” he says, “but the school [tells] you how to interact with children, or with special-needs children, or children who may have concerns or problems. Some kids have heart-wrenching concerns with questions like, ‘My daddy went to heaven. Can I see him?’ It prepares you to give special attention to each child, in the way they need.”

It’s clear that, for this career-long public servant, the season is a way to feel like he’s bettering people’s lives again.

“You have very harsh lines here and here,” says Brian Callaghan, pointing around the mouth of a classmate, one of the few beardless Santas. “It pulls the face down and makes you look angry.”

An Emmy award-nominated makeup artist and one of the many experts brought in to teach at Santa School, Callaghan is teaching us proper grooming and dressing. He applies some makeup to one side of the Santa’s face, softening the lines around his mouth and eyes. He then applies half an adhesive beard, leaving one half of the Santa’s face as a stern, straight-laced grandfatherly figure, and the other as a convincing jolly St. Nick.

As this Santa heads to a mirror to see for himself, Callaghan looks for another subject. “You!” He points to Santa Oompa, a soft-spoken American in a Christmas tree sweater. “Your eyebrows are black. Come here.” Callaghan illustrates a powder and makeup technique on one of Oompa’s eyebrows, turning it snow-white, and then scans for another victim.

He walks the class, carefully eyeing us, until his gaze falls on me. “Oh dear,” he says. “We have a lot to work with.”

The class erupts in laughter. At 32, I’ve become an ongoing joke – the child in class, better suited as an elf, not in the least because of my pointy ears. The median age is floating around the mid-60s or early 70s, so it’s hard to disagree. Attending as a nosy journalist as much as a student has also branded me a wolf in the fold. It seems the only classmates warming up to me are the three Mrs. Clauses, likely out of camaraderie as the classroom outliers. (Mrs. Clauses are trained similarly to their make-believe husbands Santas, but the glaring difference is that Mrs. Clauses – in a prime example of outdated gender roles – are given additional instruction on how to support Santas, like how to announce to a room of kids that Santa has arrived, how best to help children onto his lap, and how to help their Santas keep track of the time while on the job.)

As Callaghan closes in on me, I fear which of my imperfections he’ll highlight. There’s plenty of ammunition: my weight, my youth, my skinny jeans, the scorpion tattoo creeping toward my elbow. “Your eyes are sunken,” he says, pointing to one of my lifelong insecurities. “You have dark circles. Come here.”

He applies a foundation while instructing others on hiding tired appearances. He lightens one side of my dark “old-man” circles and bags, then releases me from his judgment, leaving me feeling like (half) a new man.

With my embarrassment out of the way, all my classmates but one seem to relax in my presence: My Santa, Santa Bob.

I overhear him sharing a story about how he got his Santa start. After he and his wife moved to Alberta, he says, a neighbouring Hutterite colony asked him to play Santa at its Christmas pageant. “The guy they used to use was kind of a drunk,” he says.

“So you live on an acreage, then?” I interrupt.

He looks at me like I have two heads. “I guess it depends what you mean by acreage,” he says, turning his back to me.

The drunk Santa in Slocombe’s story has me curious about the “Bad Santas” myth again. How common are they? I delicately ask Andrews, recalling an earlier lesson on how Santas can protect themselves from accusations of inappropriate touching. “You said that, when we take pictures with kids, our hands have to always remain visible,” I remind her. “And that Santa always wears gloves; he is never to take them off.”

Unimpressed, Andrews turns to the whole class and raises her voice. “How many people here are either veterans, or former police?” she asks. “Raise your hands.”

A majority of them go up – including Slocombe’s.

“Bob was a vet?” I ask.

“No,” says Andrews. “He was RCMP.”

Andrews says 90 per cent of her students are military veterans or retired police officers. “Most of their lives they have been serving for women and children,” she explains. “The holidays can be very traumatic [for veterans] . They have seen a lot during the holidays that isn’t what the rest of us see, but they still love to serve the public.”

The stress of the holidays can be hard on their families. There are calls for domestic disputes, suicides, violence and the like. Any time there’s a trauma of any sort during the season, it can be taxing on Christmas spirit. In the case of army veterans, there’s no family in the field, and there’s no holiday from war. Andrews can even identify it in their voices. “Sometimes when they call to enroll for Santa School, I’ll say, ‘So how long did you serve?'” she says. “They’re usually shocked that I know.”

She posits that, after years of buzzcuts, prim and proper dress, the veterans have a tendency to let their hair and beards grow later in life. Over time, they go grey and look the part. And when you look like Santa, it’s not long before someone broaches the subject, perhaps looking for a volunteer. After that, they’re hooked. After all, it’s something they’ve always done: Put on a uniform and serve their communities. Only now, they can let their hair down.

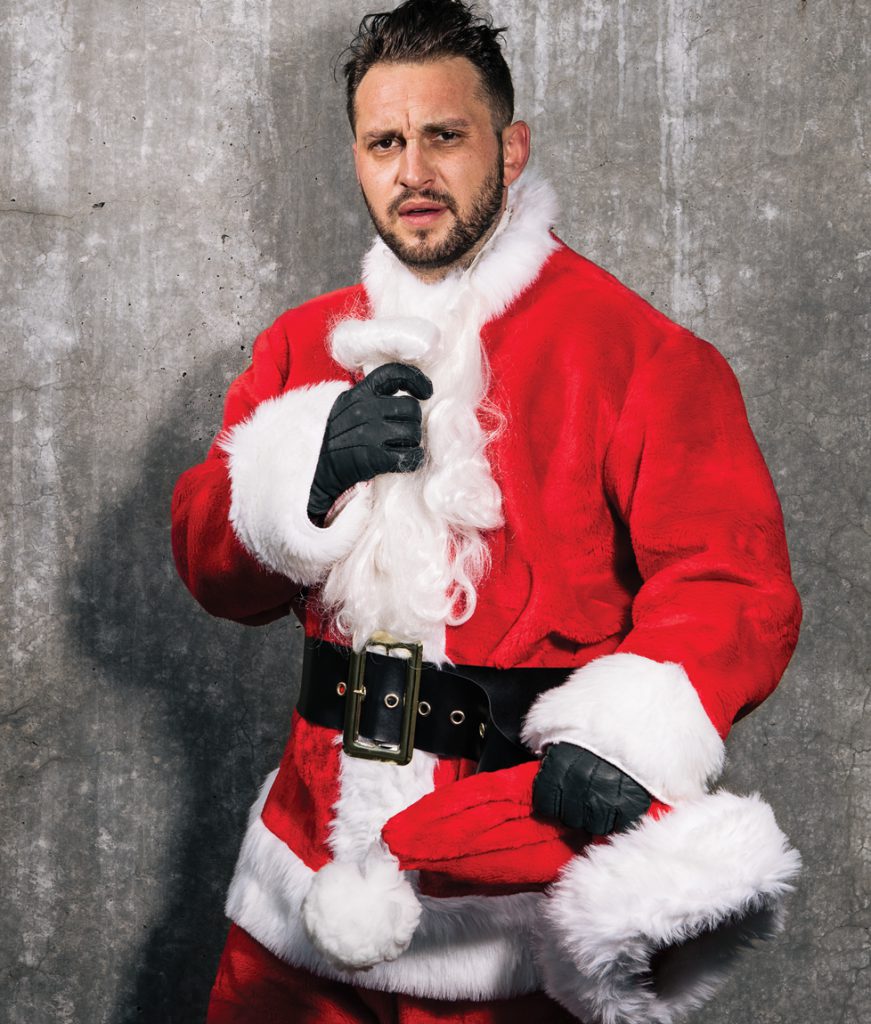

It’s time, as the song goes, to “don we now our gay apparel.” On the last day of Santa School, we put on the full regalia and become wholly transformed.

The suit is ill-fitting, belonging to my (much taller) stepfather who uses it for family Christmases, but it’ll do. I pull the fake leather boot coverings overtop my red pants. I fill out my belly with a few shirts and pajamas. Some Santas place accessories like holly in their hats. One wears no hat at all, but instead a hooded red cloak to frame his face. Santas in gloriously detailed red-and-white coats, shiny leather boots and long white gloves inspect themselves one last time, ensuring every detail is just right. It’s showtime.

A two-year-old girl enters the room with her parents, visibly upset. Slocombe, soft and gentle, takes her aside, speaking gently and paying her special attention until she smiles. All those improv lessons come rushing back as I realize the point of it was to teach us how to interact with our tough audiences and get them to mirror our pleasantness so that they too leave feeling jolly.

As I see a side of Slocombe I didn’t expect, I wonder: what will this bring out in me? What kind of Santa am I? Kind and gentle? Bombastic and energetic? An empathetic storybook Santa? Surely, as a journalist, I’ve got the skills to be an attentive, inquisitive Kringle who asks all the right questions of children and can relay to their parents the most special gift for them on Christmas Day – one they’ll love and remember forever. (I like the sound of that Santa!)

During our final exam, a “Santa Idol” contest, newbies like myself play contestants and the old guard take the role of judges. We are to make a magical, awe-inspiring Santa entrance, one that will capture the imaginations of children, and bring joy to adults.

I try to sneak in to the room, tiptoeing until someone shouts “SANTA!” And when it happens, I shake the sleigh bells and bellow my heartiest “HO HO HO HO HO! Merry Christmas, boys and girls!” Even I’m taken aback by how good it sounds.

Energetically crossing the room, I ask the “boys and girls” if they’ve been good or bad. I turn in the direction of a wailing erupting from across the room, expecting a Mrs. Claus playing the part of a crying child.

It’s Slocombe.

“Wh-wh-wh-whaaa,” he cries, huddled up in a chair, whimpering.

I approach him slowly, trying not to frighten him further. What am I going to do? Sleigh bells! I kneel down (though he remains a foot or two taller) and ring them to quell his fake sobs. When he continues, I hold them out gently, still speaking in character: “Do you see the colours, little one? Red and green, just like Christmas.”

He whimpers and reaches out for the bells. They ring at his touch and he shrivels back, but at least there are no more tears. I consider it a success.

The judges give me an adequate score. My “Ho Ho Ho” is excellent, I’m told, but my entrance needs work. And marks for the quick thinking with the bells. It’s a fair mark, I think. My vocal impression of the Santa in my head was spot-on, but was I the Santa? The one I met as a kid? I’m not sure anyone could live up to that.

On our first day, Andrews said, “Everyone has an idea of what Santa looks like to them. It could be the Santa they saw as a child or on television, but everyone has their own personal Santa.” For her, it was her father and, later in life, of course, Victor Nevada. My Santa is, without question, Slocombe. He’s a mystery to me, like Santa ought to be, but that’s not the way I intend to keep it.

Outside, Slocombe and I, still in full Santa attire, walk through the schoolyard outside the community centre. It’s autumn. Soon the grass will be covered in snow and we’ll be put to work. But until then, the golden leaves are falling from the trees we’re preparing for a group picture.

Slocombe never sat on Santa’s knee as a kid, he tells me. He grew up poor, in a log house, and was lucky if he even got a Mandarin orange for Christmas. Later in life, he and his first wife divorced; she took the kids with her, leaving him without his children on most Christmas Eves. “It was a sad time that brought back a lot of memories,” he says. Even after moving to Alberta, with his new marriage and life ahead of him, the holidays continued to bring back bad memories from his police work, and the trauma was hard for him to explain for his now wife and partner of 24 years. “For 10 years, I was a special constable with the RCMP,” he explains, “specifically dealing with domestic disputes, suicides and runaway kids.” He trails off, looks away and sighs. “But when I got involved in this” – he gestures to his suit – “Christmas became a happy time again.”

I tell him what Auntie Claus told me: it’s just his new service uniform.

Slocombe lets out a bellowing laugh – an involuntary “ho ho ho” that forces his head back, his body to shake and the bells adorning his suit to jingle.

I’m struck. It has been 24 years since I believed in Santa Claus. For an instant, I believe in him again.