As a boy, I didn’t need Jason Bourne or James Bond. I got all the Cold War espionage tales I needed from my parents.

They were two of 200,000 refugees who fled Hungary in the wake of a valiant but undermanned 1956 revolution against Soviet rule.

They huddled in the back of a truck, with small arms at their sides. They were told, if the truck stopped, to come out with guns blazing. (Luckily, they didn’t have to use the weapons.) There were soldiers patrolling the border with their dogs. My parents were among a group that crossed a cold river – winter was setting in – in order to reach Austria.

They were superheroes, 15 years before I was born. They created new lives not only for themselves, but for the three sons they were to have in Canada – and the families their sons would go on to have. I now look at my own two children, and think that none of this would have ever come to be had my parents not made that chilly swim for freedom.

We aren’t a rarity; according to the Canadian Museum of History, this country’s ethnic Hungarian population now stands at roughly 120,000 – many of those descendants can trace their parents or grandparents back to the 1956 escapees. It was Canada’s first major effort to bring in a group of refugees from one nation en masse, and it would forever change this country’s immigration policies.

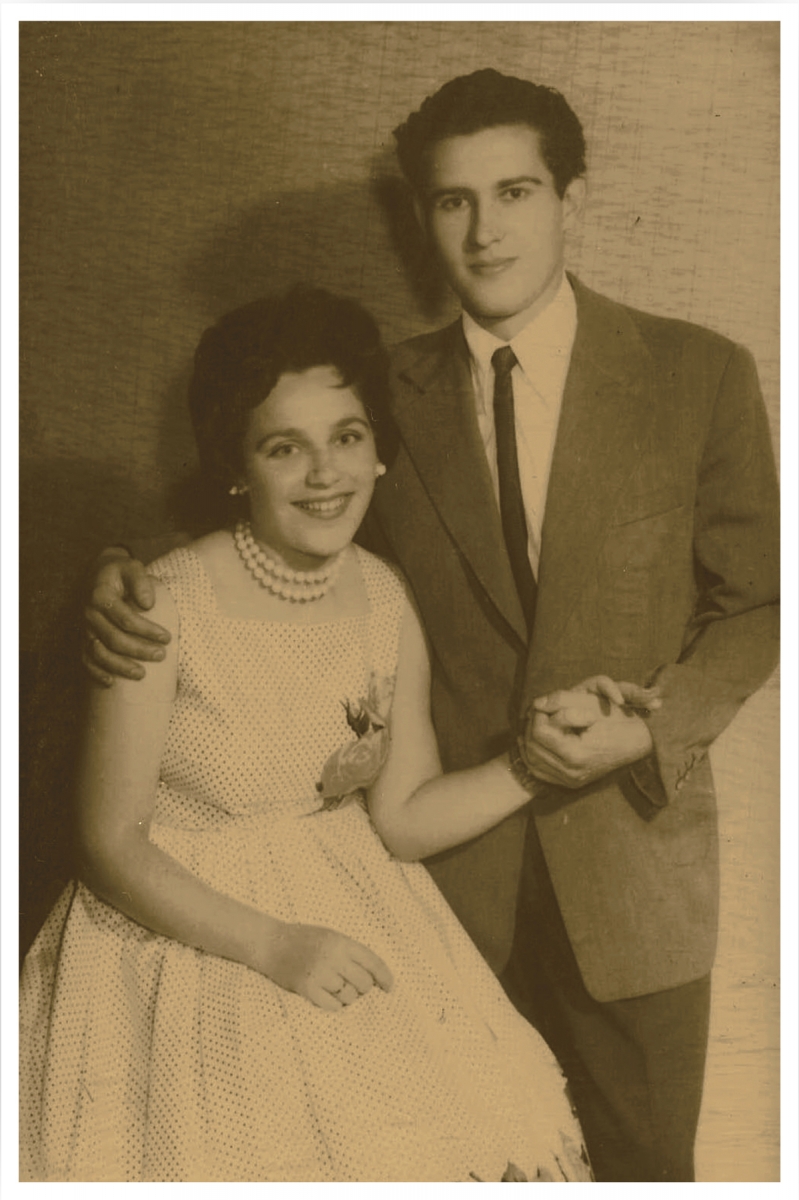

My parents were engaged when they got to the Austrian refugee camp, married when they left for Canada. They were left to discover a lot about Canadian life on their own.

Nearly 60 years later, as Edmonton prepares to welcome an influx of Syrian refugees, we’re still asking newcomers to figure out a lot about Canadian society for themselves.

Mustafa Ali was a toddler when he and his family arrived in Canada in 1991. His earliest memories are of growing up in Canada, not his native Somalia. As he grew up, he watched his parents try to settle into their new home. Mustafa Ali

“The biggest thing for them was the chance for their children to be educated, so that we have an opportunity to grow, that we could have more than we would have in our previous circumstances,” he says.

Ali is a classic example of the traditional refugee story. The parents come to Canada, knowing that their children may have chances at the kinds of lives they could never have imagined for themselves. The parents take entry-level jobs and hope that their children take advantage of the best services and schools Canada has to offer, and then flourish. My father gave up a promising soccer career in Europe to move to a nation where the sport had no cultural foothold – he traded in a life of training for a new beginning.

Ali has been a success. He helped set up an after-school basketball program for immigrant youth at Cardinal Leger Junior High School, a place where they could socialize through their love of sport. He has raised money for Haitian earthquake victims and those affected by drought in East Africa. The Mennonite Centre for Newcomers recognized him with a leadership award. Two years ago, the Alberta Council for Global Cooperation named him one of its Top 30 Under 30. He’s a prime example of the person who thinks globally and acts locally.

We sit across from each other at a table at Jasper Avenue’s Remedy Cafe, two children of refugee families. I’ve got a coffee in my hand, sickly sweet from too much sugar. He’s sipping from a drink as green as grass. We’re discussing the Syrian refugee crisis, and how we as Canadians can best prepare for the influx of people fleeing their country’s very uncivil civil war. Alberta is expecting to take thousands of Syrians – about half of them are expected to settle in Edmonton.

We speak just weeks after a federal election in which the Syrian refugees were made an issue, and there were divisive debates whether we should welcome more, less or any at all.”We shouldn’t be asking why we should help. We should be asking how we can help,” says Ali.

After all, Canada has a welcome mat that’s well-worn. We’ve provided safe haven for those fleeing conflicts in Hungary, Vietnam, Rwanda, Chile, Central America, the former Yugoslavia, East Africa and the Middle East, among many others.

According to Erick Ambtman, the executive director of the Mennonite Centre for Newcomers, with an aging population, we need as many young and middle-aged professionals as we can get. We can’t have refugees pushing brooms while they wait for their children to blossom.

We should be experts at welcoming refugees. But we’re not. Canada often over-promises what it can provide to refugees, who aren’t briefed on the necessities of daily life in their new country.

“We no longer have the luxury to wait a generation for people to make their contributions to our society,” says Ambtman, an Avenue Top 40 Under 40 alumnus.

So, how do we ensure that refugees can realize their full potential?

“We don’t do a good job in Canada of managing expectations,” says Ambtman. “For example, a person who comes here is often not told that their credentials won’t be recognized. You could have someone who was an engineer for 15 years in Nepal or Indonesia, and then, when they come here, they are told they have to start over. We have to do a much better job translating competencies. They come with the belief that they will find appropriate work.”

The story about the taxi driver or the convenience store clerk who has a master’s degree is, unfortunately, true. Ambtman even saw this bizarre case: A globally renowned heart surgeon from Jordan, trained in Germany, made trips to Canada to perform complicated operations here. He liked Canada so much that he applied for residency. As soon as the paperwork came in, he was told he could no longer perform surgeries, because Canada didn’t recognize his medical training.

But it’s more than professional development. Refugees face a series of challenges when they arrive in Canada, from finances to stress to a massive change in culture and values.

Canadians have to better understand the issues that refugees face when coming to our country. And refugees need to better understand how life in Edmonton works.

“Language is a real big one,” says Ambtman. “As well as building a rsum; you may need to learn to do it again. In Canada, we don’t want pictures in the rsum; we don’t want to know your sexual orientation. It’s also about how to make a bank deposit, how garbage disposal works and how to use transit.”

So, how do we improve our system? By learning from the stories of refugees who have gone through it.

My mother recalls that the camps weren’t orderly. “That had nothing to do with the Canadians,” she says. “It was because of the Hungarians.”

She says when she and my father arrived in Canada, they were herded like cattle onto a train and sent across the country to British Columbia.

“No prime minister met us at the immigration centre,” she laughs. My mom and dad, Mary and Karoly Sandor, had this portrait taken shortly after arriving in Canada.

When they got to Vancouver, they were boarded in a jail. They spent days living in a prison before being settled into the city. Not such a great introduction to Canada, was it?

The Syrians Canada receives won’t be sent to a jail. But they will be used to the herd mentality of the refugee camp. In a perfect world, a United Nations refugee camp would be a place where everyone gets along and people take their turns in food lines. But it’s not like that; a camp is under constant threat from outside, and overpopulated by desperate people who will do what they have to in order to survive.

“Most government-sponsored refugees who come to Canada are in refugee camps for five, 10, 15 years – some for their whole lives before they come here,” says Karin Linschoten, a senior therapist at the Mennonite Centre for Newcomers. “So, they don’t have one trauma or two traumatic experiences. They have a life of trauma. That’s because most refugee camps are not safe places. That’s one of the big myths I came into this work with – I had thought, at a refugee camp, you don’t have much, but it’s safe. But it’s not like that.”

Why aren’t they safe? Location, location, location. Linschoten says camps are often found just across the borders from trouble spots. Usually, frontier areas don’t have the resources needed to help the refugees cope. Often, military men or rebels will stroll across the border and recruit young men out of camps; the refugees are repatriated by force. Linschoten says that women are sometimes pulled back across the borders to become sex workers or – dare we use the term – slaves.

In the camp, there aren’t polite lineups for food aid. You can hear the sounds of war from across the border.

Often, families employ the strongest boys to fight so their families can get vital supplies. The men are often gone or dead, so it’s teenage boys who become the champions for their families. People get mugged for their supplies. Some carry weapons in the camps. The survivors learn the way of the camp. They know not to stick to set schedules – that way, if they are being targeted, their movements aren’t predictable. They live in a place where mistrust rules.

“You learn to live without planning,” Linschoten says.

But, if a refugee shows up late to an appointment in Canada, the stereotype is that he or she is lazy or mooching off the system. However, that person has been programmed to think that it’s safer not to get there right at 9 a.m.

“People come here and they’re learning that the things that they did just to survive are now things they shouldn’t be doing here,” says Dr. Vivian Abboud, who came to Canada from Lebanon. She’s an Avenue Top 40 Under 40 class of 2015 member and the new chair of the Institute for Canadian Citizenship, a national organization that looks to enhance citizenship ceremonies for newcomers to Canada.

Before coming to Edmonton, she lived in Beirut. She recalls crumbling buildings in her neighbourhood. Her father was kidnapped.

“You have become used to living in a rush; you do everything in a hurry, because that’s how you live and survive.”

Every now and then, my parents would hint at some of the horrible things they’d seen – from both sides of the conflict. They remember the Soviets targeting hospitals. They saw people run over by Soviet tanks. My father, who passed away eight years ago, once told me he saw someone torn apart by bullets just a few feet from him. My mom recalled secret police officers being trussed up and then slowly stabbed to death by angry Hungarians armed with pocket knives.Syrians will come here with all sorts of scars that can’t easily be seen.

Edmonton Public Schools already has four “reception centres” for newcomers to Canada located at Queen Elizabeth, Harry Ainlay, Jasper Place and J. Percy Page high schools. When a Syrian family arrives, they’ll be able to stay in temporary housing for up to 14 days to get themselves sorted, to focus on their health and housing. Once permanent housing is established, they’ll register their kids at their local schools. Each school has access to an English as a Second Language (ESL) consultant.

The entire family will be referred to the closest reception centre, where they will be assessed. Mental health experts can be called upon, knowing that many families, when they first come to Canada, don’t open up about the things that they saw or experienced in the countries from which they fled.

Linschoten says that a lot of refugees try to keep any issues or potential issues hidden. There is a general fear among their communities that any “unreported illness” could get them deported. They don’t know that post-traumatic stress disorder doesn’t count as an “unreported illness.” So, for fear of immigration officials, they may stay quiet.

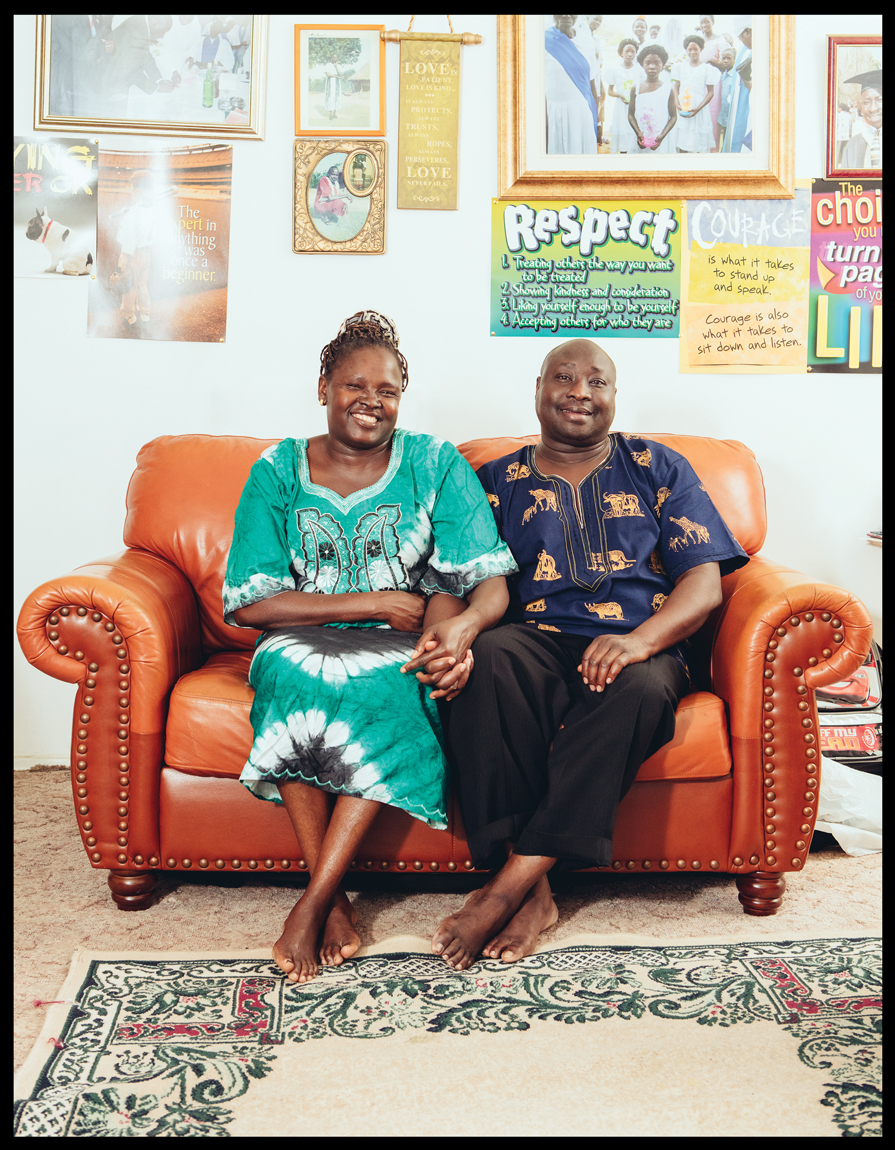

Joseph Luri fled civil war in Sudan. He arrived in Canada 18 years ago. Luri is now a settlement practitioner with the Mennonite Centre for Newcomers, helping students settle at their new schools in Edmonton. Joseph Luri

“As soon as you come to Canada, all of those things that happened if you were exposed to war – the torture, the killings – all those things come again to mind,” he says. “And all of those loved ones left behind – you can’t come with every one of your relatives or everyone you care about.”

“On a biological level, your nervous system has to be constantly on alert,” says Linschoten.

“If I go to the downtown area, Boyle Street, when it’s dark, my nervous system is in a different state than when I sit with you here. It’s like, ‘I’m alert. Who’s coming up behind me? These people over there are fighting.’ If you are in this state for 20 years, your nervous system, it’s like a rubber band. It has been overstretched. The nervous system is meant to be stretched, to be alert, but then to relax. If I go for an hour in the middle of the night downtown, no big deal. It’s OK; my nervous system can deal with it. I am going to calm down. But if you are in that alert state for 10, 20 years, your nervous system loses some elasticity. It has been overstretched for so long that, actually, it can’t relax in the same way anymore.”

My mother wasn’t the only member of her immediate family who escaped Hungary. Her twin brothers – my uncles – also decided to leave. Her mother – my grandmother – left as well. But they left at different times. When you made a plan to escape, you kept it quiet. That was because, if your family got questioned about your disappearance, they’d have no information to give up. The Russians and Hungarian secret police had ways of making people talk.

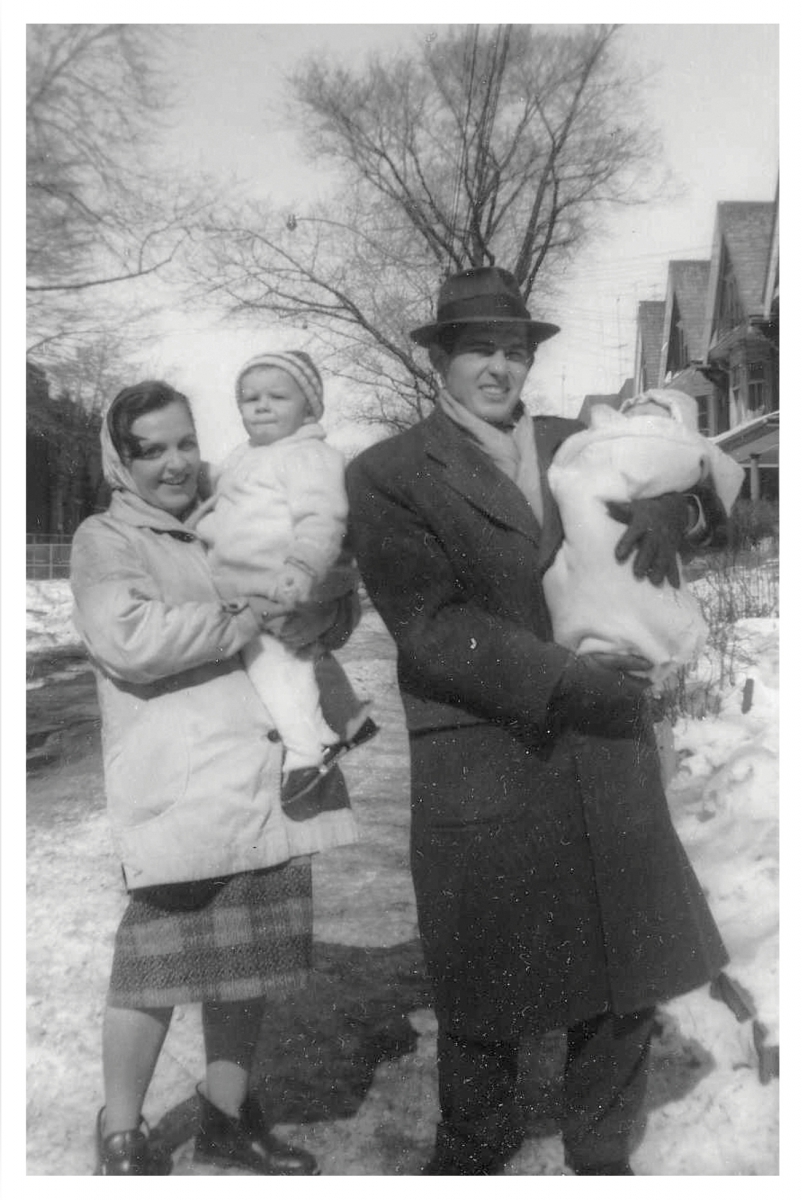

When my parents were in the camp, they located my uncles through the Red Cross. They found out the twins were alive and well in England; my parents were then assigned to be sent to the United Kingdom. Two days after my parents were married, they found out my uncles were on the move to Canada. So my mom and dad wrangled the paperwork to come to this country instead. My grandmother, who originally went to West Germany, later joined them in Toronto. My mom and dad with my two brothers, Toronto, circa 1960

My parents had each other. But, Luri had to leave his wife behind in what is now known as South Sudan. He waited for another five years before she joined him in Canada.

“It was terrible,” Luri recalls. “I was just patiently waiting. There was nothing I could do. I went to Nairobi [Kenya] twice, to the Canadian embassy, and they told me, ‘Sorry, it was all online and we are doing it. There was nothing special we can do for you.'”

Luri expects to see a lot of separation anxiety amongst the Syrian refugees who come to Edmonton.

Esther Yangi and Joseph Luri were forced to spend five years apart

“The worst-case scenario is the family that has been separated. If there are two brothers and a sister, then the sister has gone away. The sister may be looking for her two brothers – she doesn’t know if they’re alive or not – and then she gets the opportunity to come here. Does she enjoy this changed life, or the good services she is getting here? Because she’ll say, ‘I don’t know where my brothers are.'”

When my parents arrived to Canada, they were given one major edict: Learn one of Canada’s official languages in just one year – or else. So it’s no surprise that, when a refugee family arrives in Canada, a lot of classroom time will follow. The kids are placed in schools; the adults will need to go to English as a Second Language classes.

For the adults, going back to school isn’t that easy. Linschoten says that a person who hassuffered years of trauma probably won’t be in optimal shape to sit and listen in class.

“If you have someone with a lot of trauma in the background, their capacity to learn is impaired because they are not able to relax to the level where their whole [mind] can absorb information,” she says. “If they come, they go to school. They have to; it’s part of the agreement. Now the classroom is quiet, nothing is happening. So what do you think might happen? All the memories, all the bad stuff can rear up and be right there. So they sit there and try to learn, but what actually happens is all that stuff now comes up.”

It would be a lot simpler if classes were put together by mother tongues: a class for Arabic speakers, another class for native Spanish speakers, and so on. But it doesn’t work that way. Migrants from around the globe mix in the classes, and they are all working to understand the instructor.

“Going to ESL, even if it’s part-time, it’s three hours, and if it’s full-time, it’s about six hours,” says Luri. “That is a long time. And they’re never comfortable. And there is only the teacher, and you’ve got to figure out what he’s talking about. Because, while he or she is teaching, there is no one there to interpret for you.

“You may be lucky and get someone in your class who speaks the language that you speak but who has also had some degree of education. And, yes, you can use that person if he or she is kind enough. But that person can also see you as a source of disruption and might think, ‘I need to pay attention to what I am trying to learn here.'”

Many refugees come here thinking that they wouldn’t be under the gun to learn English, because they’re French speakers. French is spoken widely through North Africa and the Middle East.

Abboud, who spoke French when she arrived from Lebanon, was shocked to find out that the majority of Edmontonians didn’t have command of the language; after all, she’d been told this was a fully bilingual country.

The textbooks about Canada are clear. We have lots of open spaces. It gets bitterly cold in the winter. But one big myth that passes from textbooks to the refugees is that everyone in Canada is functional in both English and French. Many come here with French skills thinking that they’ll have no issue getting by in downtown Edmonton or ordering a coffee at a Tim Hortons.

Suzanne Gross, manager of strategic initiatives at the Edmonton Mennonite Centre for Newcomers, says that people coming to Canada are briefed before they come to the country – but the advice they get isn’t reliable.

” [We hear that] they’re getting their advice from the people who work at the embassies,” she says. “These people aren’t Canadian; they just work at the embassies. In a lot of cases, they’ve never lived in Canada.”

Every country’s education system is different. What a child learns in Grade 3 in Alberta might not be close to what a child the same age learns at school in the Middle East. And language is, of course, an issue. Luri’s job is to help students adjust to their new Canadian school lives. And he has dealt with kids who have had to cross cultural barriers in the classroom.

He counselled a refugee student who stood up every time his teacher entered or left the classroom, because that’s what students did where he grew up. As well, in his culture, you never looked a superior in the eye – it was a sign of disrespect. So, whenever he spoke in class, he looked down at his shoes. And, despite assurances that Canada didn’t have corporal punishment, he was certain that missteps would lead to the strap.

But schools are better equipped to deal with these cultural challenges than ever before. That’s because they’ve already had a lot of practice. According to Marlene Hanson, Edmonton Public Schools’ supervisor of diversity education and comprehensive school health, there are already 22,000 students in the system who are considered to be “English-language learners.” That is, about a quarter of the Edmonton Public Schools’ students do not consider English to be their first language. That’s five times the number of English language learners in the system a decade ago.

Currently, there are about 700 students coded as refugees already in the school system.

Hanson says that the city is expecting to get 800 Syrians who are sponsored by the federal government; that’s not counting those who would be privately sponsored. It’s a significant number, but given that Edmonton Public Schools has been welcoming newcomers for years, they know what to do.

With so many language learners already in the system, teachers are given the tools to integrate diverse learners into their classrooms.

“We say that every teacher is an ESL teacher,” says Hanson. “Every teacher has to be able to modify lessons in his or her classrooms… We accommodate diversity. For example, we have prayer rooms for different religious practices in some of our schools. Or perhaps a school may provide a space for First Nations students to smudge. And we have found that children are quite welcoming. In a lot of ways, they are more resilient than the adults are.”

When Hanson was teaching, there was a massive influx of Vietnamese refugees. She remembers that she did her best to integrate the Vietnamese kids in her class but, today, teachers have more tools to use. There are social workers and mental-health therapists at the ready. Teachers are often the ones who spot the symptoms of lingering trauma in refugees. Remember: these are kids who fear bombs every time they hear an airplane, or think that a cardboard box on a sidewalk could be camouflage for an explosive device. These are kids who have spent extended periods in tent cities.

These kids also have to re-learn – or maybe learn for the first time – to trust adults.

“They are in the camps because the adults did not resolve their conflicts by talking,” says Linschoten. “Now they come here, and they may copy what they have seen their whole lives. They might do what they need to do to survive. They might do that in the school system and then get suspended.”

But it’s not just the kids who go to school. Ambtman says the Mennonite Centre’s waiting list for English classes is close to 300 people; currently, 400 students take classes at the Mennonite Centre’s 82nd Street headquarters, 400 take classes at Eastwood School, and approximately 200 more get English lessons in community halls and religious centres throughout the city.

I came home from grade school one day and told my dad about the visitor we’d had in class: A real-life police officer! I remember how the prospect of having a cop in class made him scowl. He warned me about “people who like to wear uniforms.”

Many refugees come from societies where they feared those in uniform, from members of the military junta to secret police who make loved ones “disappear.”

Ali remembers growing up with two very separate sets of rules. There were the values that his parents taught him, based on what they knew from years of Somalian unrest. And then there were the values that were being taught in his Canadian school.

“That was a big challenge, the cultural clashes between what my parents heard and taught and what society taught. There was a divide. The first thing was the relationship with law enforcement. For people who grow up in more difficult societies, military states, there is a different view of police.”

The second challenge was something that most Canadians would likely expect to be our greatest strength when welcoming migrants and refugees – our multicultural mosaic. Ali says that, at first, his family was surprised, though not offended, by Canada’s pluralistic society; many refugees are on the run because the countries from which they come aren’t very tolerant. When a refugee first arrives in Canada, the notion that people of different colours and creeds can live and let live seems almost too good to be true.

As well, he says that many refugees have struggled to embrace our political system. When they get their citizenship, they can go out and vote – or even run for office. But, until the most recent federal election, many of these new Canadians stayed out of the process. Think about it this way: If you’re a refugee, you come to Canada because it’s safe, because there are no bombs in the streets and kids aren’t being conscripted by gunpoint. Many of these people have never lived in a society where there has been a real election, or where political discourse is encouraged. So, the entire Canadian system is met with apathy, especially when refugees see that the government is still run by old-establishment white males.

Ali points out that, while there have been changes in the federal government, there is currently only one woman on Edmonton city council and no visible minorities. Ali ran an unsuccessful campaign in Ward 2 in the 2013 municipal election.

Mustafa Ali

“You feel more invested in governmentwhen you see yourself reflected in that government,” he says.

The cultural transition is even more difficult on women.

Abboud, by strict definition of the word, is not considered a refugee, because the official reason she left home was to follow her future husband, whom she met in Lebanon, back to Edmonton. But she always knew that she needed to leave; for a woman with strong career hopes, Canada was a better place to be.”Canada is a place where human rights are more valued, and that’s especially true for women,” says Abboud.

One of the talks that needs to happen is about gender roles – or the lack of them. When Luri arrived in Canada, he was stunned to see public displays of affection. Nothing as elaborate as seeing two teens in an endurance lip-lock on the bus; just the simple act of a couple holding hands in public floored him.

“Where I came from in the Sudan, we had implementation of the Islamic Sharia law; I am not a Muslim myself, but it was imposed on everybody. So, you don’t get to hold hands. You don’t kiss anybody. You don’t do anything. So, I come here, I see people holding hands, I see kissing – that becomes a shock as well. You begin saying, ‘Whoa,’ because you are still living in the fear that you will be taken to the market and there will be some flogging.”

For many coming from the Third World, where archaic gender roles are still rigidly enforced, a place where a man does the tidying up around the house and looks after the kids while wife is out working is a very foreign thing. We can’t just expect people coming off the plane to be progressive if they’ve never had discussions about equality in their homelands.

Luri explains: “So, here is a man who has been brought up in a society where he is a breadwinner and he distributes. Now, they could be in a [Canadian] system where the wife has all the money and is going to manage it, and so it puts the man at a disadvantage, where he feels like, ‘Well, I am powerless. I don’t have anything.’ It brings a lot of discomfort; in most of the cases, it is one of the sources of conflicts that arise within married couples, and you see families falling apart. There are changing roles of the partners in the family, where the men come predominantly from a society where they don’t do feminine duties – cooking, cleaning, looking after children, changing diapers. These are what are considered feminine obligations. But once you are here, the woman engages you and says, ‘You know what? I am tired, so you can help me with this and do this.’ And when the tone of the voice is not the right one, it creates conflict and then the family quickly falls apart.”

A refugee can find comfort in staying close to other refugees from the same part of the world. But staying tight to one’s ethnic group can also slow the transition process.

Abboud says that the reason so many immigrants settle on low-skill jobs is because those vocations allow them to keep to themselves. They don’t have to learn English; they can go to work and go home to their family, and there’s no worry about needing to integrate into Canadian life any more than they have to. All it takes is a new arrival to hear, “Sorry, can’t help you,” two or three times before they settle for a Joe job and accept that it’s his or her lot in life to push a broom.

She believes that, if the new arrivals are encouraged to take active roles in their communities, they won’t be as likely to barrack themselves within their own ethnic groups.

“If all you need to worry about is making a living, you don’t need to worry about integrating,” says Abboud. “If there’s no integration, then you begin to live in isolation. I fought against that. It’s extremely dangerous to not be involved in your welcoming community at large.”

And there are cultural hurdles to leap. Abboud says that Beirut is still a city where the pursuit of wealth trumps community; it is a city filled with poverty and political strife, but also with German high-performance vehicles. People only take the bus if they’re too poor to drive. She recalls taking the bus to Campus Saint-Jean and weeping because that’s how low she thought she’d sunk; that, after coming to Canada, Abboud was now lowered to the bus-riding caste.

But, for a lot of refugees, just getting on the right bus is a victory. The numbers and place names are confusing.

“The challenge is, you have to go to school,” says Luri. “With going to school comes the taking of buses. And some who came from those refugee camps and some of those villages, there were no buses. And, here, there are so many of these buses, and you see them with numbers and names, and you ask, ‘Which one is right?’ And somebody can tell you 10 times, and it doesn’t click in the mind.”

Opening a bank account is tough, too. So is making the move to an apartment.

“There’s a worry of how to use appliances,” says Luri. “For some of those who come from the villages who went into refugee camps, they’ve never used electricity or these cooking utensils or hot water. In the village, you go and fetch water miles away. So it’s strange that water is just here. And it all contributes to a kind of anxiety.

“Having a bank card with PIN numbers, this is totally something new. Mail is coming to your box at the door. We don’t have these kind of systems in most of the Third World countries. And so, sometimes, a newcomer gets important mail, but just throws it away.”

Banking is stressful. Transit is stressful. And so is, believe it or not, a Canadian supermarket. How stressful can a supermarket really be? Think of it in reverse. You have spent your entire life going to the grocery store for your staples. Now, you are moved to a country where food is sold in the open market. There are no price tags on any of the meat or produce. You have to haggle. And none of the food is familiar; instead of apples, peaches, berries and grapes, you see strange-smelling, exotic fruit.

Now, to someone who grew up in an Asian or African culture of haggling, having to put all of the items into the cart and then pushing it to a cashier will be very strange. An apple or a blueberry is an exotic, strange item.

“There, in the Third World countries and the refugee camps, it’s an open market,” says Luri. “Here, you go to the Superstore, you go to the Safeway. Now, you have to take transit again; you go there, you pick what you want and you go and pay. That means, again, using a bank card; that means the PIN number. Not only that, the goods you are going to buy from the store are not the goods that you know. These are totally new food items for you… they are not traditional food items; that again poses a challenge and stress. It’s changing in Edmonton because there are a lot of other cultural foods that are now available. When I came, there was completely nothing… Looking at the shrimp, looking at hot dogs – where I came from, I didn’t even know of anything called a hot dog.”

Hanson believes that the first step in welcoming Syrians is to stop calling them refugees. To her, it’s a word that carries a stigma, one that suggests someone is simply coming to Canada simply for shelter. It doesn’t take into account that the person will become a contributing member of Canadian society.

“They are children, they are youths, they are newcomers,” she says. “We need perspective. Newcomers need to be recognized for the human beings that they are.”

My mom and dad got here nearly 60 years ago. To me, they’re not statistics. They represent to me exactly what it means to be Canadian; to come here with nothing, and to build something. Edmonton has the chance to be the place where thousands more something-from-nothing stories can happen. To help them, we need to take what we’ve learned from the immigration waves of the past and put them into practice.