The killer who doesn’t want to be a killer anymore. It’s not exactly a new theme in the world of literature. From Jason Bourne to James Bond – you lose count of the many times the British superspy has quit Her Majesty’s Secret Service – there are many literary series dedicated to the assassin who can’t escape his nature.

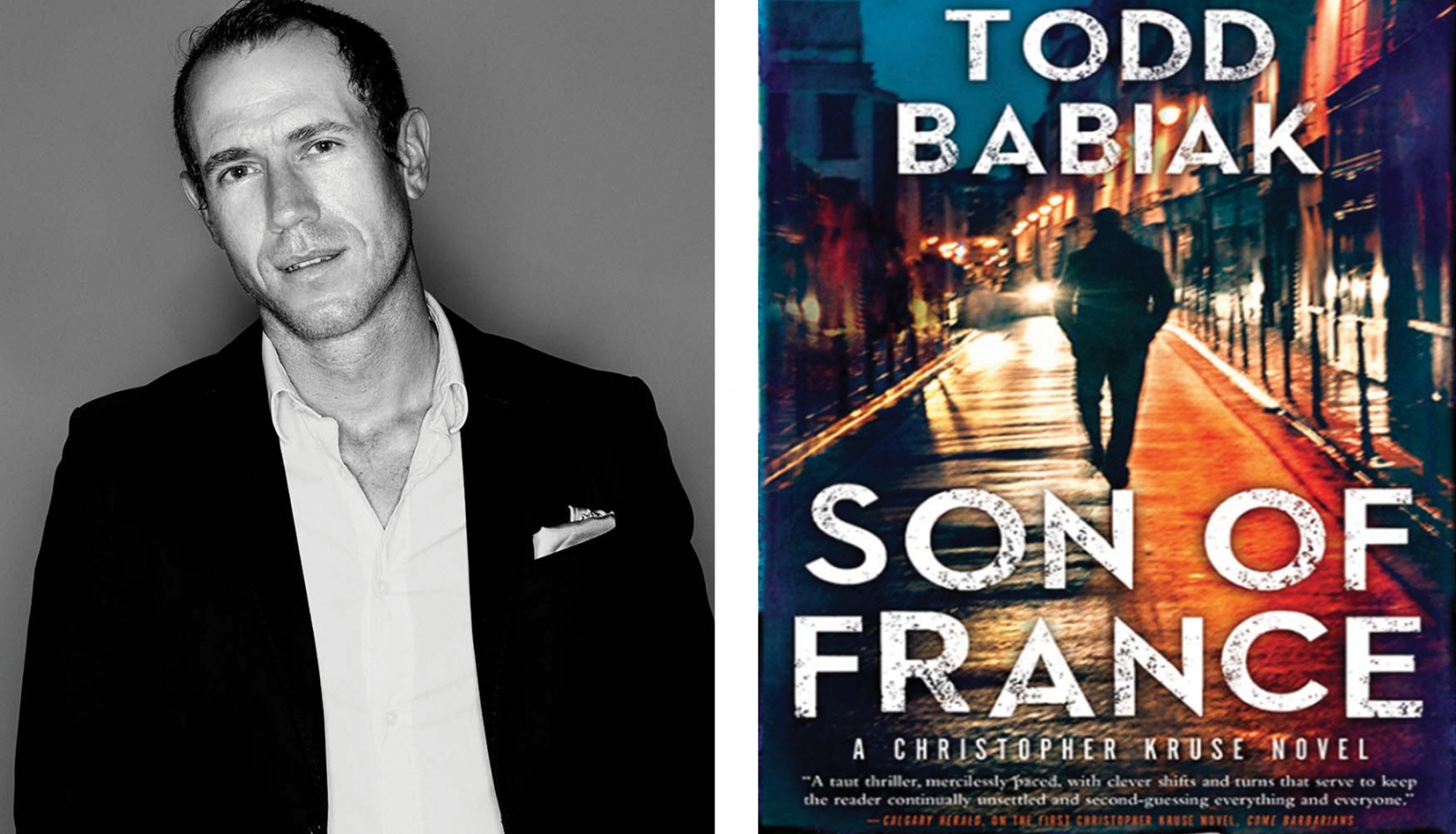

But, the antihero of Edmonton author Todd Babiak’s Son of France, Christopher Kruse, holds his own. Released this summer, the book is the second Kruse adventure, following the poetically brutal Come Barbarians.

The structure of Son of France is more straightforward than the first Kruse adventure – in the first chapter, the reader barely has time to assess the surroundings before things start to blow up. The reasoning is sound; we’re familiar with Kruse from the first novel – we know why this Canadian mercenary tried to begin a new life in France with his wife and daughter. And, we know how badly that ended. Kruse isn’t exactly an old friend by book two, but we also know what he is – the brutal killer who loses sleep or cries into his hands after he does his dirty deeds.

Set in the early 1990s, Babiak captures a Europe that struggles with its postwar, post-rise-of-America identity. The old guard mistrusts Europe’s push towards eliminating its borders. Kruse and his old mentor/business partner are tasked to assassinate the man who ordered the bombing of a Paris restaurant; from there, Kruse deals with red herring after red herring, as the body count piles up.

The timing of Son of France‘s release isn’t comfortable – a book that relies heavily on bombing attacks in Paris was released in a year when France is reeling from tragic incidents. If anything, it makes Son of France a slightly more timely read, despite the fact that the book is set in the 1990s.

But the pacing is fast – in fact, you wonder if Babiak is channeling the-climax-every-chapter nature of Ian Fleming’s Bond nevels – minus the overarching racism, of course.

This article appears in the September 2016 issue of Avenue Edmonton.