Before she had a restaurant of her own, MRKT chef and co-owner Carla Alexander rose through kitchens where it wasn’t uncommon for her colleagues to deride her with chauvinist jokes. Sometimes, she was spun around and forcefully kissed. On one occasion, a man threw cornstarch in her face.

Prior to becoming Culina Muttart’s head chef, Stephanie Alcasabas worked in a banquet kitchen where the mostly male brigade insistently challenged her strength. Meanwhile, they left the general cleaning duties for her, because it wasn’t a man’s job.

On her first month as an apprentice chef at a Michelin-star Berlin restaurant, Doreen Prei endured daily tests of her strength that bordered on sexual harassment. After a particularly grueling shift, the executive chef followed her to the elevator, dangled his keys and commanded her to wash his car. “I went home many times questioning whether I should proceed with my career,” says the former head of culinary development/chef de cuisine of the now-closed Edmonton Petroleum Club.

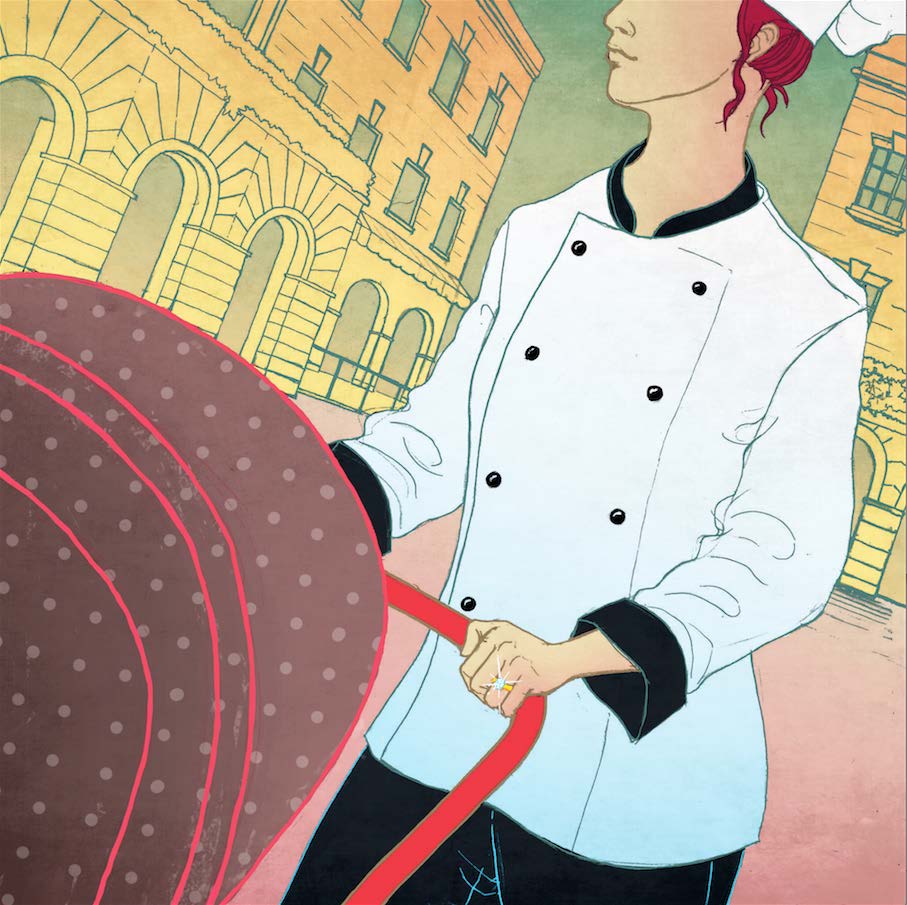

Alexander, Alcasabas and Prei’s stories are unusual only in that they come from Edmonton women who’ve risen to the ranks of chefs de cuisine. In the age of the celebrity chef, it’s hard not to notice that the city’s “it” restaurants – and many of the faces you’ll find in Avenue‘s annual Best Restaurants issue – belong to men. It’s not that there aren’t women behind Edmonton’s grills and ovens. There are hundreds in largely anonymous positions, garde mangers and pastry chefs, whose names never make the menu. They might leave for the low-testosterone, low-prestige world of catering, or exit the industry altogether.

It’s not a local phenomenon. As of November 2014, 10 per cent of the Canadian Culinary Federation’s 376 executive and sous chef members were women, who also represented 24 per cent of nearly 2,200 members. The American Culinary Federation posts similar statistics. Even though a young woman will likely exit her teens with more cooking experience than her brother, on paper and in the collective conscious, her brother is more likely to be the chef. She, a cook.

Just watch Food Network Canada for a day: From 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., prim, aproned ladies stir and whisk with swivelling hips in front of outfit-matching appliances. But once daddy’s home, the TV oozes machismo – barking mad bruisers making co-stars sweat and cry, or virile travellers who defy nature, ingesting gut-busting street foods that drip condiments onto callused fists. The few women in prime time – the bossier the better, like Anne Burrell – are just female versions of the hardened male archetype. Moreover, she and her female counterparts arrive as novelties, something this very article can’t help but perpetuate by virtue of its subject.

“People like this idea of a hip guy in the kitchen. They’re rough around the edges, they’re rugged,” says Alexander. “The viewers and customers are just used to seeing that.” Perhaps that’s why some MRKT clientele are more likely to pass their compliments to sous chef Dick Hemphill before her. “He does a great job, so he deserves to hear it, but because he’s a man – a big burly guy – people think, ‘That’s the guy who made my beautiful food.'”

That a woman’s place is in any kitchen but a professional one is not a new sentiment. It was 65 years ago that Fernand Point, famous for fathering modern French cuisine and having a 66-inch waistline, infamously mansplained, “Only men have the technique, discipline and passion that makes cooking consistently an art.” But that notion is changing. The total number of Michelin-star restaurants with female head chefs nearly doubled over the course of 2009 alone, for instance. Or consider the Canadian Culinary Federation’s membership numbers. Ten years ago, says executive director Roy Butterworth, he’d have recorded about three female executive or sous chefs. More promising is that women now make up about 60 per cent of those enrolled in culinary school. “The growth is phenomenal,” he says.

Slowly the Canadian kitchen is sweating out the bro-fest. The minority chefs – not just women, but LGBTQ – have reached a boiling point. They’re taking control, promoting their own and demanding more inclusive kitchens.

The lineup in NAIT’s cafeteria looks about what you’d expect at a trade school. Young men in hoodies and overalls, curved ball-cap brims crowned with sunglasses, backpacks slung over shoulders. It’s 9 a.m. They groggily file forward toward an open kitchen and order the most basic breakfasts: Eggs, bacon, French toast. But the simplicity of the food doesn’t make it less intense for the culinary students behind the counter.

On her first day, Christine McLean struggles to keep up with the many moving parts of her role, the least of which is taking orders. By her side, instructor chef Mike Maione keeps her arms moving with blunt directions: “Break the egg.” “More bacon!” “Don’t forget the hash browns.” After 30 minutes, she’s getting the hang of it. “There you go,” he says encouragingly.

In the back, others are pounding patties, mashing avocados and lugging vats to prepare lunch. It’s much quieter, as there’s no hierarchy in the unsupervised kitchen. Less noticeable is the demographic makeup. Of the nine third-semester students, six are women, double what you’d see two decades ago. Between 1999-2000 (the earliest records available) and 2011-2012, female enrolment in the School of Hospitality and Culinary Arts grew from 44 to 56 per cent. Women now consistently represent the majority of the student body, which in itself has grown by more than half. In fact, a few years ago, NAIT converted a men’s change room to women’s to accommodate them. (However, there are still only two female instructors out of 20 in the Culinary Arts program.)

“We are brought up to think our place is in the kitchen,” explains student Theresa Baxter while caramelizing onions over a flame grill. But too often those skills stay domesticated instead of being nurtured into a profession, she explains. “Now we’re saying, ‘screw that.’ If we’re going to learn how to cook, we’re going to make money from it.”

Baxter wants to return to her roots and explore the culinary possibilities on the East Coast, a dream not dissimilar from other classmates inspired by the Food Network and locavore movement. But she stands out because she’s the mother of a 17-year-old daughter and an 11-year-old son, and she’s entering her third career. Most of her contemporaries have a reverse trajectory: They begin as young chefs before leaving the industry to raise a family, rarely returning.

From food consultants and instructors to chefs and restaurateurs, the majority of those interviewed for this article repeated that family is the single biggest inhibitor to the rise of women in the culinary world.

“It’s really difficult to keep women after maternity leave,” says Gail Hall, a chef and consultant behind Seasoned Solutions. For 18 years, she ran a highly successful catering company employing 95 people. “The situation was chronic. We’d have great [female] Red Seal chefs, but they just wanted to get married and have a family.”

Never mind that open flames and sharp knives breed machismo. Ignore the Anthony Bourdain wannabes. What it really comes down to, says Alexander, is a lifestyle choice. “It depends on what these women want. Say you want to work nine-to-five, because you want to be a mother – this industry isn’t going to work for you. You’re either a good restaurant owner and chef or you’re a good parent. And I’ve got a child – named MRKT. It’s five years old.”

Must a mother choose between family and the business?

Prei doesn’t think so, and understanding that is the first step to making her kitchens more tenable to women. “I know exactly what a woman means when she says I have to pick up my child, or get to daycare, or my child’s sick,” says Prei, who was on maternity leave when the Edmonton Petroleum Club decided to close its doors in November. She carried her first child as Zinc’s sous chef, while on her feet for up to 14 hours a day. After returning from leave, she was promoted to chef de cuisine, though the hours and weekends only made it harder to be with her child and partner. “It can be heartbreaking to know your baby’s crying and you’re on the line calling tickets,” she says, adding that she’d like to make sure male chefs have a great understanding for mothers, too.

The experience made her sympathetic to her female colleagues, whom she makes a point of hiring, promoting and encouraging. Prei has them butchering meats and filleting fish, the prototypically masculine roles that men guard. “Usually [women] are pushed into corners doing pastry or garde manger – washing the salad and the lettuce.”

Inclusivity is gospel for Nathin Bye. He has a reputation for forming diverse kitchens, first at Wildflower and now at his own Ampersand 27. In the back-of-house, there are three women, four straight men and two gay men, including himself at the top of the chain. Executive sous chef Michael Stevens-Hughes is straight, but he has a gay sibling and transgendered parent. The Ottawa transplant sought out Ampersand 27 not only for the cuisine, but because he knew it was a safe zone from the typical homophobia one might overhear while pouring souffl batter into a ramekin.

Compare that to the environment at a hotel where Bye worked 14 years ago. The young apprentice found himself working in pastry alongside the only two women in a 35-person brigade. “We were the butt of so many jokes,” says Bye (whose last name in itself made for fodder). On more than one occasion, managerial members hatefully called him “faggot” – and that’s when they would actually talk to him. The rest of the time, they avoided Bye and only communicated to him through conduits. But without a single dominant demographic at Ampersand 27, the chef-owner has noticed the banter in his kitchen is less sexual and the ribbing is equal-opportunity.

Restaurateur Brad Lazarenko is also known amongst local chefs for creating a welcoming environment for women. At Culina Mill Creek, Culina Muttart or Bibo, you’ll find many more women in the kitchen than just Alcasabas. “We all kind of understand each other,” says Muttart’s executive chef. “It’s more helpful, as opposed to working with guys where it’s like, ‘Oh, you can’t do it? Too bad. Do it anyway.'”

Lazarenko acts oblivious as to why Culina has been historically female-dominated. But when the question is posed to Alexander, who cut her chops at Mill Creek, she attributes it to his shyness. It makes him less commanding and micromanaging, thereby engendering a pleasant environment. It was Lazarenko, after all, who convinced her to return to the culinary world after she’d quit. ” [Lazarenko] knows that a kitchen is different when it’s all women or all men.”

Before Alexander worked for herself, she was always trying to prove that she was tough enough, strong enough, that she didn’t take things personally. She threw on a tomboy attitude until she could ball-bust with the best of them. Alexander did or said whatever she had to in order to fit in – until she realized how toxic that was to her talents. “It’s hard to be inspired and cook great food when you’re having pissing contests.”

Like this content? Get more delivered right to your inbox with Ed. Eats

A list of what’s delicious, delectable and delightful.